Hong Kong News

Would-be Hong Kong drivers wait more than 1 year to sit road tests, auditor says

Prospective drivers in Hong Kong can wait more than one year to take a road test, while the delay before sitting a motorcycle exam at some assessment centres increased by about 280 per cent over a seven-year period, a government auditor has found.

The Audit Commission on Wednesday called on the Transport Department to shorten queues for driving tests in a report on the city’s licensing services for motorists, which concluded that the waiting time for non-commercial vehicle exams had “increased significantly” between 2015 and 2021.

In Hong Kong, those who wish to drive a non-commercial vehicle, such as a private car, light goods vehicle or motorcycle, must be assessed at either a government test centre or a site at one of the city’s four designated driving schools.

Residents looking to sit an assessment last year for a private or light goods vehicle at one of the four schools were left waiting about 410 days after applying, the report found.

Meanwhile, those looking to get an assessment at a government test centre to drive a motorcycle, private car or light goods vehicle waited between 257 and 322 days in 2021.

In terms of percentage, the most significant increase in waiting times for an assessment was for motorcyclists applying at government test centres on Hong Kong Island, rising by 284 per cent from 67 days in 2015 to 257 in 2021.

At one test centre on the island, the auditor found that the waiting period for an assessment to drive a light goods vehicle rose from 118 days in 2015 to 320 days last year, accounting for an increase of 171 per cent.

The commission also said that transport authorities between 2015 and 2019 had underutilised their test centres for assessing applicants seeking to drive non-commercial vehicles.

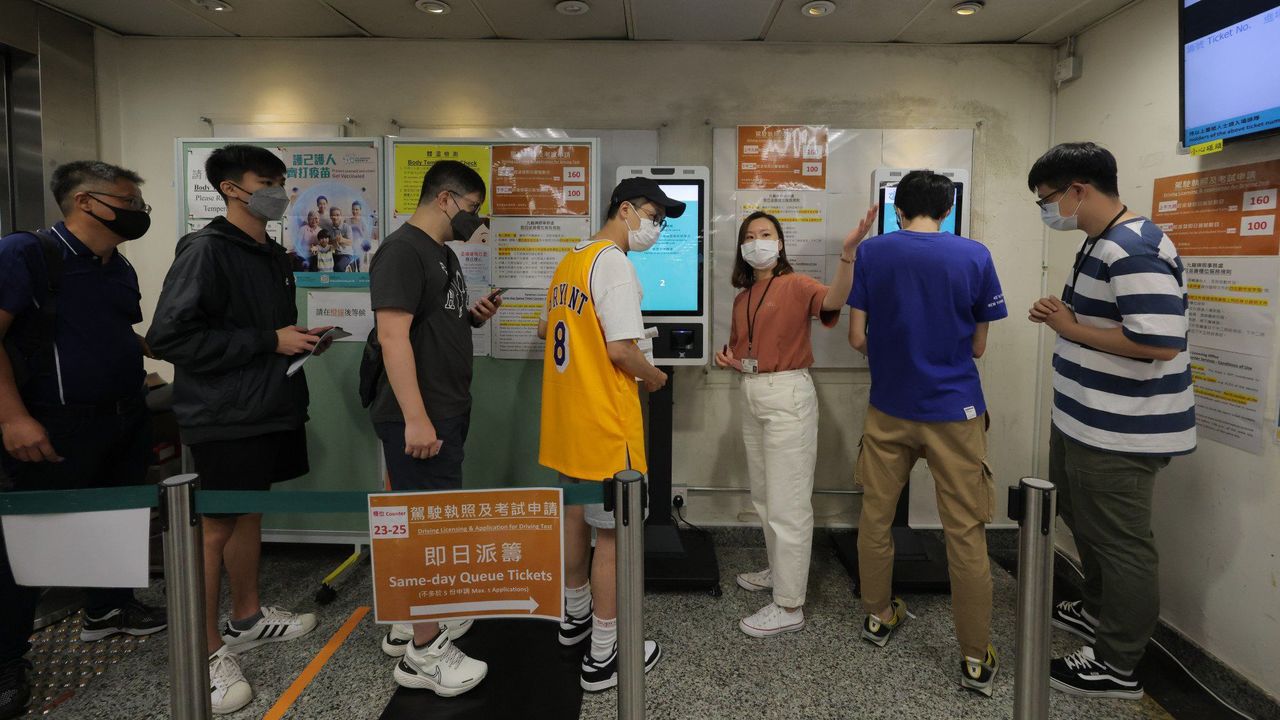

Would-be drivers wait to receive a ticket for an appointment at the Kowloon Licensing Office.

Would-be drivers wait to receive a ticket for an appointment at the Kowloon Licensing Office.After surveying 13 such facilities, the commission found that seven had failed to achieve a utilisation rate of more than 80 per cent in 2019, up from 5 per cent in 2015.

The auditor calculated the rate by dividing the number of available testing days at each centre by the total number of working days in a single year.

In response to their findings, the government auditor called on the Transport Department to reduce the waiting period for driving tests by “streamlining” the duty reporting arrangements for examiners, which currently required them to report to the main testing centre in Ho Man Tin on a daily basis before being randomly assigned to another site.

The auditor suggested authorities reconsider a proposal to inform examiners of their assigned centre via instant messaging, allowing them to travel there directly and further streamlining procedures.

The commission also advised the government to introduce new technologies at centres to improve efficiency, highlighting that transport authorities in July had already switched from paper forms to electronic ones on tablet computers.

Other proposals included in the report included regularly updating the questions used in the written test for drivers, which is based on the Road Users’ Code, a document last updated in 2020 after remaining unchanged for two decades.

Numerous regulatory changes and legislative amendments since 2000 were not included in the code and written test before the 2020 update, including a ban on using handheld mobile devices while driving, the commission explained.