Hong Kong News

Why are Hong Kong lawmakers demanding change, scrutiny of power companies?

IT programmer Jacque Chan, 43, watched with alarm as his electricity bill soared from under £30 (US$36) to more than £120 a month during his first year living in Derby, England.

The Hongkonger, who emigrated with his girlfriend and daughter early last year, said: “I can survive without air conditioning now, but I can’t picture how difficult winter will be if energy prices don’t go down.”

In Berlin, software engineer Timothy Choi, 26, said if the German government had not capped electricity prices in December amid soaring inflation, he would be paying 70 per cent more this year.

“Inflation is eating up my money,” said the Hongkonger who is based in Berlin and lives by himself in a 400 sq ft flat. “I paid only €506 [US$544] last year for electricity, but it has increased to about €738 this year. Without the price limit, I would have to pay more than €850.”

HK Electric’s Lamma Island Power Station is a coal and gas-fired facility.

HK Electric’s Lamma Island Power Station is a coal and gas-fired facility.

In Hong Kong, housewife Kathy So, 50, who lives in Wan Chai with her husband, said their electricity bill rose only slightly from HK$477 (US$60) in February last year to HK$501 this January.

“I don’t feel the shock at all. Our electricity bills have been steady since we moved into our flat in late 2020,” she said.

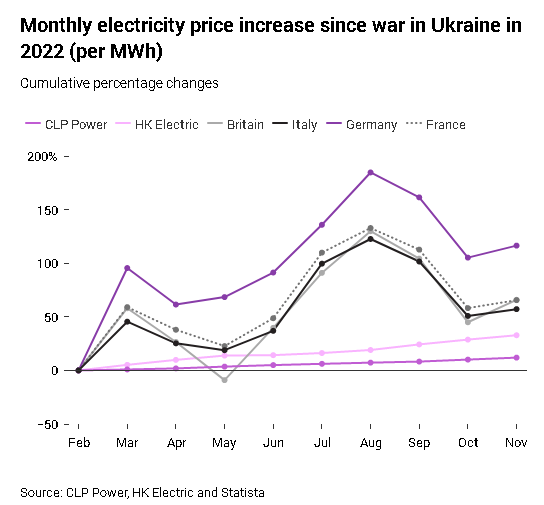

The year-long war in Ukraine has become almost synonymous with the international energy crisis. But Hong Kong, despite being predisposed to global fluctuations, appears to have suffered a lighter blow.

Financial Secretary Paul Chan Mo-po said in his latest annual budget that he would grant a HK$1,000 electricity charge relief to 2.9 million households and extend the current HK$50 monthly tariff subsidy to the end of 2025.

Experts told the Post Hong Kong’s electric power system had succeeded in providing a reliable supply of relatively low-cost energy.

The city’s two power companies are allowed a fixed level of profitability, beyond which surpluses are returned to consumers as rebates. But lawmakers feel both need to be reined in further, especially after they raised tariffs.

Western sanctions against Moscow following its invasion of Ukraine a year ago led to a sharp reduction in supplies from Russia, the world’s second-largest producer of natural gas after the United States.

The war in Ukraine has affected fuel prices around the world.

The war in Ukraine has affected fuel prices around the world.

In the ensuing market upheaval, US gas futures skyrocketed from US$3.94 per unit in February last year to US$9.71 in August, the highest level since 2009.

According to the International Energy Agency, Russia supplied almost 40 per cent of the European Union’s fossil fuels before the war, exporting 155 billion cubic metres of natural gas to the region in 2021.

Moscow retaliated for Western sanctions by slashing European gas supplies drastically. European Commission data showed that Russian gas fell to only 12.9 per cent of the region’s needs by last November.

That month, Hong Kong’s two power companies – CLP Power and HK Electric – raised tariffs by 19.8 per cent and 45.6 per cent, respectively, from a year earlier.

Lawmakers accused the firms of being unreasonable and lacking social responsibility.

The Legislative Council went on to pass a non-binding motion last November, urging the government to suppress the tariff increase, with some lawmakers saying the authorities should review their approved profit level.

“The government must … suppress the tariff increases of the two power companies and set aside part of the permitted returns to alleviate tariff increase pressure,” the motion said.

It urged the government to raise subsidy amounts to ease the pressure on low-income families.

Several legislators, including Edward Leung Hei, Simon Lee Hoey and Tang Fei, called on the government to develop new sources of power supply to help lower the burden on residents and bring down electricity prices by introducing competition.

Then, on February 27, both companies announced they were raising their tariffs again, this month.

CLP Power, which supplies electricity to Kowloon, the New Territories and most outlying islands, said it would charge about HK$1.55 per kWh. HK Electric, which supplies Hong Kong Island, Ap Lei Chau and Lamma Island, set its price at around HK$2 per kWh. HK Electric then further increased its tariff to HK$2.05, to take effect on April 1.

They said the increases were necessary, reflecting higher fuel prices in the previous quarter, and consumers would not be severely affected.

The rises meant an average household of three people would see their bill increase by HK$5.70 per month if they were a customer of CLP Power, while HK$33.68 more if their power was supplied by HK Electric.

The companies’ actions sparked calls from lawmakers to review the government’s control over the two electricity giants, including the level of profit they are allowed.

Environment minister Tse Chin-wan said although the government saw the urgency to suppress price increases, any changes to the existing agreements had to be agreed upon by both power utilities.

Jimmy Kwok Chun-wah, chairman of the government-appointed Energy Advisory Committee, said the agreements gave utility companies an incentive to invest continually in newer, more efficient facilities.

Finance chief Paul Chan said in his latest annual budget that he would

grant a HK$1,000 electricity charge relief to 2.9 million households.

Finance chief Paul Chan said in his latest annual budget that he would

grant a HK$1,000 electricity charge relief to 2.9 million households.

“Fierce competition in a free energy market discourages investments in electric generators,” he said. “Without an agreement, companies might not take the risk of building new power stations because these are massive investments.

“In an open market, you never know how many years your business can stay afloat. It is too difficult to calculate the recoverable cost. But Hong Kong needs a strong and stable energy supplier for its dense population.”

The Hong Kong government’s contracts with the two companies have succeeded in providing reliable, affordable electricity supply for decades while ensuring they receive a guaranteed return on investments.

The first was signed in 1964 with CLP Power, the larger of the power two, and the one with HK Electric in 1978.

New clauses added to the agreements upon renewal called for replacing old coal plants and using cleaner energy sources to help slow the impact of climate change and reduce air pollution.

The companies were initially allowed to earn 13.5 per cent of the net value of their respective fixed assets, but this was lowered subsequently to 9.9 per cent.

Under the latest agreement signed in 2017, which would last 15 years, their rate of return was lowered further to 8 per cent.

Any surplus earnings over what is permitted will go into a tariff stabilisation fund to be used as rebates for customers the following year.

Yuen Long experienced a rare power cut last June when high-voltage cables caught fire.

Yuen Long experienced a rare power cut last June when high-voltage cables caught fire.

According to information from the two companies, HK Electric is expected to have a surplus of HK$390 million and CLP Power HK$276 million by the end of this year.

The companies and the authorities insist the current system worked, noting Hong Kong scored “99.999 per cent” in power supply reliability, with rare large-scale outages.

When Tuen Mun, Yuen Long and Tin Shui Wai experienced a two-day blackout last June caused by a fire from high-voltage cables, CLP Power faced a fine of up to HK$16 million under the agreement. HK Electric has no record of a major power outage.

Hong Kong has not experienced anything like the severe power disruption in Macau when Typhoon Hato battered the city in August 2017, severing electricity supplies for more than 40 hours in some areas.

Kwok said that in a city as densely populated as Hong Kong, no one would dare risk opening the market and exposing it to such uncertainties as in Europe.

“Without the control agreements, it’d be difficult for Hong Kong to plan its power demand,” he said. “If the power companies weren’t under check, we couldn’t ensure that they would produce electricity responsibly.”

Latest statistics show that despite last year’s price rise, CLP Power’s operating earnings from Hong Kong increased by 2.6 per cent year on year, while HK Electric recorded a 6.9 per cent drop in the same period.

CLP Power said the fuel cost involved in generating one kilowatt-hour of electricity varied depending on international fuel prices, among other factors. HK Electric said such information was “commercially sensitive”.

In Hong Kong’s system, the power companies control all four stages of the production process, from generation to transmission, retail and distribution.

Tracy Cheung Ting-ting, an energy policy postdoctoral fellow at the University of Queensland, said the two companies operated as “de facto monopolies” protected by government contracts.

“In Hong Kong, energy customers have no choice. The two power companies decide on energy tariffs, while customers can only decide how much electricity they use,” she said.

Cheung, who has studied Hong Kong’s model and that in Europe, which has liberalised its electricity markets since the late 1990s, acknowledged that the city still fulfilled its objectives of providing reliable, low-cost energy.

A survey finds that most Hongkongers think reliability and safety of electricity supply are of the utmost importance.

A survey finds that most Hongkongers think reliability and safety of electricity supply are of the utmost importance.

“The main feature of a liberalised system is that the four core stages have been unbundled and, in theory, are run by different companies. The rationale is to ensure transparency and open the energy market to competition by enabling access to new players,” she said.

The idea of opening up the market has been raised before. In 2015, the environment authorities held a three-month public consultation on whether to introduce competition in the electricity market.

Most respondents said they found the city’s power supplies to be reliable, safe and affordable, and they did not see the need to introduce competition simply for the sake of adding more choice.

“Some respondents considered that reliability and safety of electricity supply were of utmost importance,” the report of the consultation said. “Competition should be introduced only if it brings benefits to consumers without compromising these two important objectives.”

Then environment minister Wong Kam-sing said the government would not make any changes right away but would pave the way for market liberalisation in the longer term.

A 2019 document by the Legco Secretariat said that there was “no conclusive evidence that market liberalisation would naturally lead to a reduction in electricity prices”.

In documents submitted this month to Legco, both power companies indicated that electricity prices would be adjusted downwards in the middle of the year as international fuel prices had declined.

CLP Power earlier this month said it would freeze its fuel adjustment surcharge at 62.8 HK cents per kWh between April and June.

HK Electric on Monday announced it would further raise its surcharge to 90.6 cents per kWh in April, bringing the overall rate to HK$2.05 per unit.

Still, legislators Kwok Wai-keung and Michael Luk Chung-hung, of the pro-labour Federation of Trade Unions, remained eager to find ways to lower electricity tariffs further.

They wrote to Legco this month, demanding that both companies increase the transparency of their fuel procurement strategies and details of the fuel clause allowing them to adjust tariffs regularly to reflect fluctuations in the cost of fuel or bought power used to supply electricity.

“At present, there is no way for us to know whether they did their best to source the cheapest fuels possible. Their operations are like a black box,” Luk said.

“As long as the costs CLP Power and HK Electric spend on fuel are 100 per cent reimbursable, they have no incentive to look for cheaper energy sources for residents.”