Hong Kong News

What we know, and don’t know on how Beijing will reform Hong Kong politics

Beijing has dropped yet another political bombshell by declaring that Hong Kong must drastically revamp its electoral systems to ensure only “patriots” hold key positions in all three branches of government as well as the city’s statutory bodies.

But Xia Baolong, director of the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, who laid down the principles and directives in a closed-door meeting on Monday, stopped short of spelling out the plan’s concrete elements, raising more questions than answers.

Here is what we know – and do not know – so far about what could be the biggest overhaul of the Hong Kong electoral system in its brief history.

Who are patriots and who are not?

What we know:

Xia made it clear in his speech that effective measures must be put in place to prevent “unpatriotic” figures from taking up positions of political power in Hong Kong.

These people, he said, included those who favoured “laam caau” – the “mutual destruction” strategy that sprang out of the 2019 anti-government protests, attacked Beijing in a “hysterical manner”, advocated independence, smeared Hong Kong in the international community, called for foreign sanctions or endangered national security.

What we don’t know:

It remains unknown how far the definition of patriotism will extend or who will be responsible for determining who meets those parameters.

Executive Council member Ronny Tong Ka-wah said “patriots” – in a political sense – could be legally defined. “Those who successfully have their oaths validated can be seen as patriots,” he said, referring to the government’s Tuesday amendment to the Basic Law’s Article 104, the Oaths and Declarations Ordinance.

Pro-democracy lawmakers resigned from Hong Kong’s Legislative Council en

masse last November after four of their colleagues were disqualified

from serving.

Pro-democracy lawmakers resigned from Hong Kong’s Legislative Council en

masse last November after four of their colleagues were disqualified

from serving.

The city’s leader, principal officials, Executive Council members, lawmakers and judges must take an oath of office under the ordinance, pledging to uphold the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution, and swearing allegiance to Hong Kong as a special administrative region of the People’s Republic of China.

“Those who fail to pass, in other words, are not patriots,” Tong said.

But opposition activists – including the leaders of both the Democratic Party and Civic Party – have argued Xia’s definition of patriots was very vague and would simply provide officials with a handy excuse to disqualify election hopefuls.

The scope of application

What we know:

Xia said that, in “every circumstance”, key posts in not only the executive, legislative and judiciary branches, but also appointments to important statutory bodies must not be taken up by anyone “who goes against China and disrupts Hong Kong”.

What we do not know:

It is unclear how the 268 statutory bodies currently helping the government form policies and make decisions might be affected by the reform or whether foreigners will still be able to take up influential leadership positions in the future.

Critics have raised concerns over whether the impartiality of these important bodies – such as the Securities and Futures Commission and the Equal Opportunities Commission – would be hampered by the new political requirements.

One source familiar with Beijing’s thinking believed the “patriot rule” would apply only to chairmen – who set out the board’s direction – rather than the chief executive officers of these bodies.

Ip Kwok-him, a local deputy to the National People’s Congress, said he thought not even all of the bodies would be affected, but only major ones such as the Hospital Authority and the Monetary Authority.

“These are important organisations that affect the smooth running of the government. Thus, they should be headed by reliable officials that are deemed patriots,” he said, adding that the Hong Kong government would soon explain which statutory bodies would be affected.

Former Democratic Party lawmaker Andrew Wan Siu-kin, however, feared the new measure would create a monolithic environment in these powerful bodies. “Without countering forces, they may lean towards vested interests,” he said.

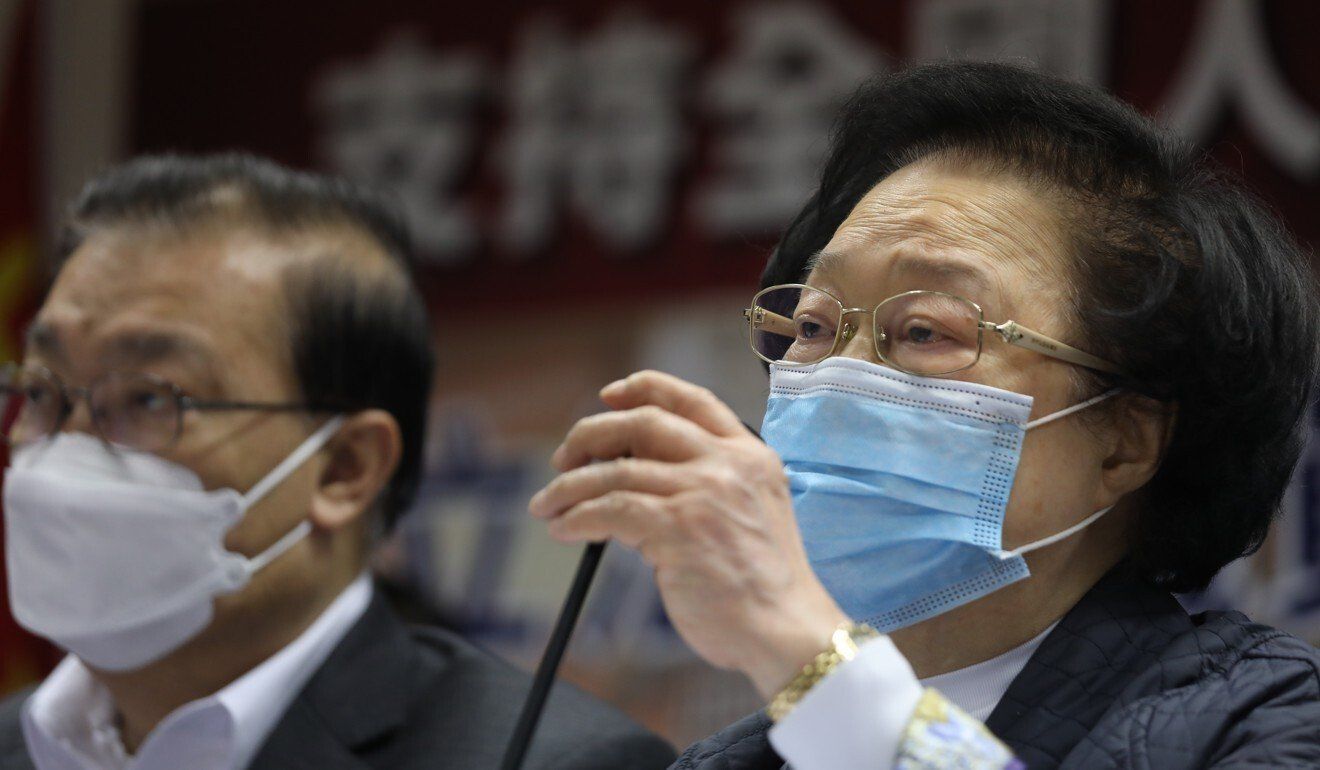

Maria Tam (right), vice-chairwoman of the Basic Law Committee, said

circumstances at Legco mean only Beijing has the necessary power to

effect the coming changes.

Maria Tam (right), vice-chairwoman of the Basic Law Committee, said

circumstances at Legco mean only Beijing has the necessary power to

effect the coming changes. The Hong Kong government’s role

What we know:

Xia said Beijing would take the leadership role in revamping the city’s electoral system, but promised to communicate with the local administration and consult different sectors before initiating the changes. Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor was also quick to point out on Monday that her government had no power to implement political reform on its own, that it respected Beijing’s decision to take the lead, and would fully cooperate.

What we don’t know:

The actual processes that will be used to introduce the Beijing-led changes remain a question mark.

In the past, the Hong Kong government would have had to go through the so-called five-step procedure, with changes eventually approved by a two-thirds majority in the Legislative Council.

Maria Tam Wai-chu, vice-chairwoman of the Basic Law Committee, pointed out that the five-step mechanism was not currently applicable as the city did not have enough lawmakers left to endorse the proposal following the mass resignation of opposition members in November.

A total of 15 opposition lawmakers quit en masse last year in protest of a Beijing resolution which effectively unseated four of their colleagues.

“We are now faced with an unprecedented situation. We only have 44 legislators … So if any election-related changes are to be made, my personal view is they can only be done by exercising power stated in the [Chinese] constitution,” Tam said, referring to an article that outlines the power of the National People’s Congress to decide on the systems instituted in China’s special administrative regions, which include Hong Kong.

However, only a simple majority in Legco would be needed to pass the local legislation following a Beijing resolution.

Ip estimated that Beijing’s resolution and accompanying details would be created through the National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) much as the national security law was last June.

Concrete details of the Beijing-imposed legislation were announced on the same day the NPCSC passed it unanimously on June 30 and listed it under Annex III of Hong Kong’s Basic Law

In 2014, during a previous attempt to revamp Hong Kong’s political systems, the local government launched a five-month consultation exercise. It is uncertain if any similar efforts will be made this time or how much say the city and its government might have over Beijing’s proposed changes.

Democratic Party leader Lo Kin-hei, meanwhile, had only scorn for Xia’s promised consultations, predicting they would be neither comprehensive nor transparent.

What the exact proposals will look like

What we know:

Xia said that anti-China and radical separatist forces had entered the governance structure of the city via elections, including those for the Legislative Council, the Chief Executive Election Committee and district councils, indicating the scope of the coming changes to the electoral system will be extensive.

What we don’t know:

But Beijing has not yet spelled out how the changes will be made. Sources from the pro-establishment camp said Beijing was still in listening mode as different parties submitted their own proposals to the central government.

One of the leading proposals would encompass a complete revamp of the current voting system in picking lawmakers, which uses proportional representation to allocate seats in the Legislative Council, a system that allows candidates with a small but fervent support base to win seats.

Some have proposed breaking down the city’s five geographical constituencies into 18 smaller ones, with two seats allocated to each. The pro-establishment camp believe that would prevent opposition candidates from scoring a landslide victory such as that seen in the November 2019 district council polls, while also making it harder for candidates deemed radical to win.

Other pro-Beijing veterans have suggested an overhaul of the election committee that chooses the city’s leader by scrapping all 117 seats likely to be controlled by opposition district councillors and replacing them with either representatives to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference or others from pro-establishment sectors.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam declined to disclose a timetable for the looming changes when asked on Monday.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam declined to disclose a timetable for the looming changes when asked on Monday. When will the changes take place?

What we know:

Chief Executive Lam refused to disclose a timetable for the overhaul when asked on Monday, merely noting there were three elections coming up in the next 12 months: the Legco elections, which were previously postponed to September; the election committee polls later this year; and the chief executive elections next March.

What we don’t know:

When exactly the proposals will be unveiled and how long the process will take remain unknown. But all eyes will be on the annual plenary sessions of Chinese People’s Consultative Conference and National People’s Congress in Beijing early next month where the issues are expected to be discussed.