Hong Kong News

What it means for Hong Kong if the world turns against the US dollar

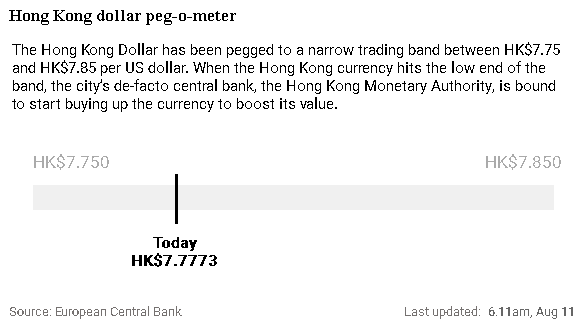

Could the US dollar lose some of its shine in the currency markets? It is possible. And that would have implications for the value of the Hong Kong dollar versus non-US currencies given that, via the linked exchange system, Hong Kong’s currency is pegged at between 7.75 and 7.85 to the US dollar.

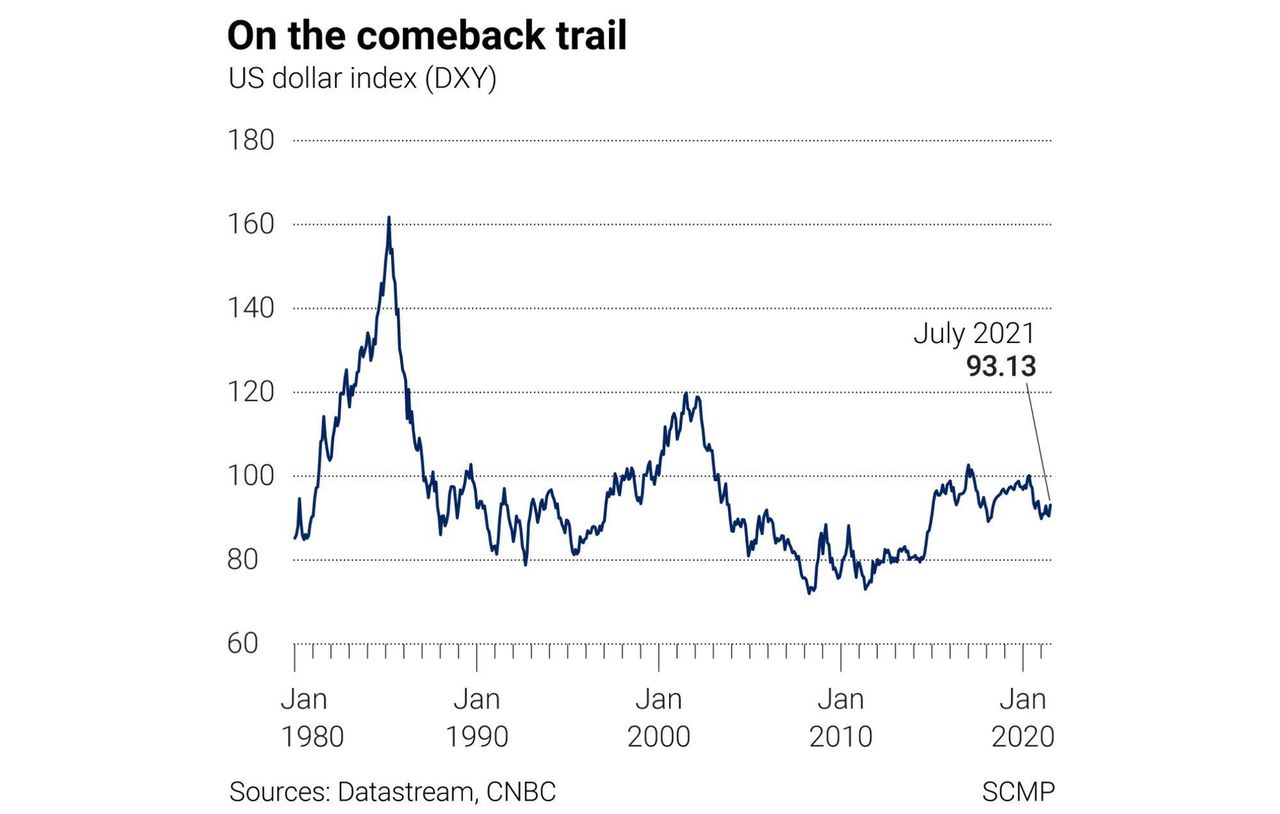

It might seem odd to talk of possible US dollar weakness, when it is still the most dominant currency in the global economy and has been performing pretty well on the foreign exchanges, but what goes up invariably comes down.

Capital flows into the “safe haven” dollar were most pronounced in the first quarter of last year as Covid-19 spread across the world. In part, such flows are likely to continue to support the dollar’s value, with the pandemic still raging.

But the pandemic is becoming endemic. Covid-19 is not going away and the world will have to adapt to live with it.

Unless foreign exchanges see the widespread existence of Covid-19 as supportive of the US dollar in perpetuity, currency markets will necessarily reassess what are to be the key drivers of dollar value.

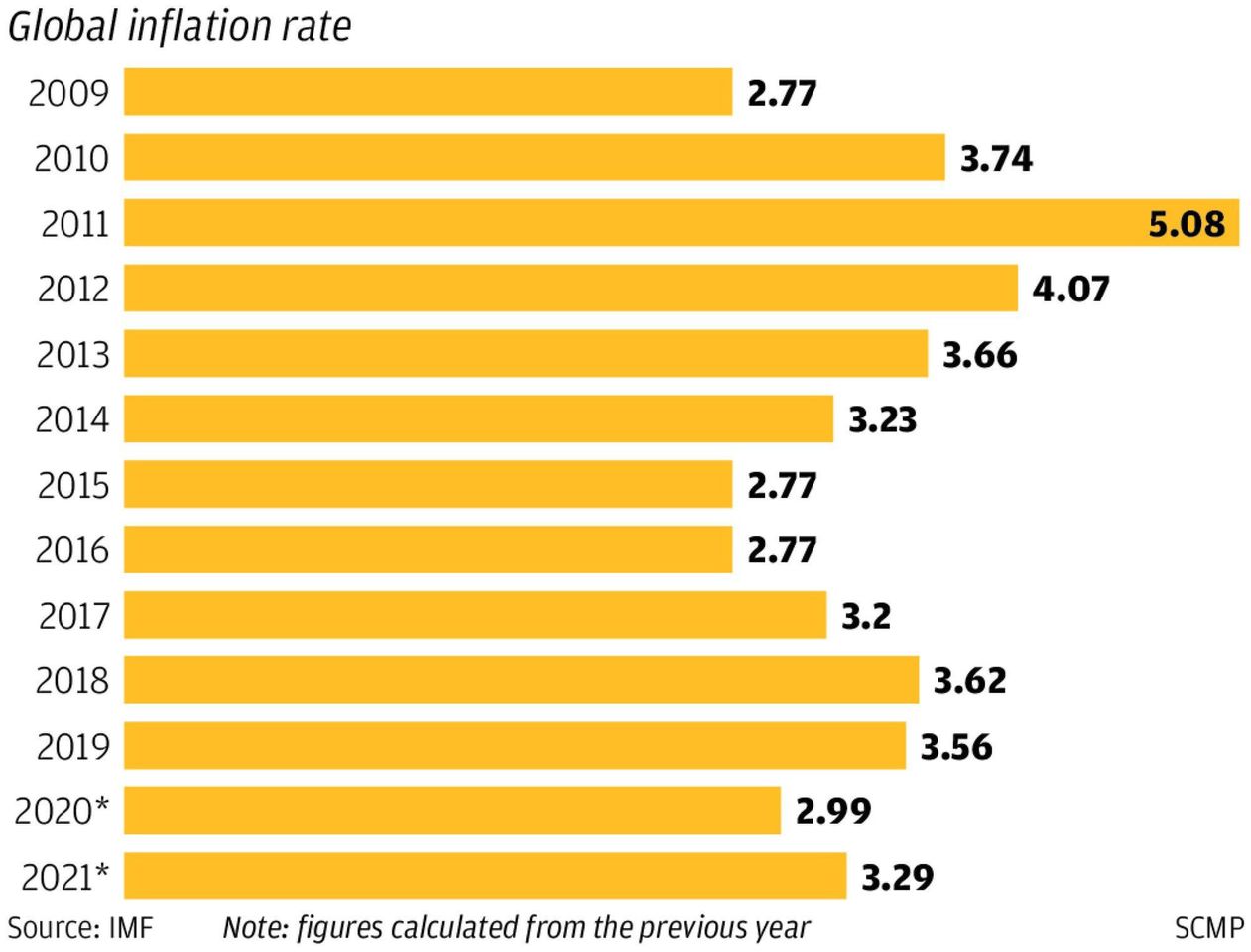

Recent rises in US inflation may trigger such a reassessment. With the Federal Reserve sticking to its ultra-accommodative monetary policy settings even as some other central banks are addressing local inflationary pressures, foreign exchanges may conclude that the US central bank is being too tolerant of rising prices.

In recent weeks, both the Brazilian and Russian central banks have raised interest rates in response to a build-up of local inflationary pressures. New Zealand

and South Korea look set to increase rates later this month, and Norway might well follow suit in September.

Elsewhere, the Bank of Canada has begun to taper asset purchases while Australia’s central bank could do so next month.

None of the currencies of these countries could individually be characterised as rivals to the US dollar but, collectively, they offer the currency markets an alternative if sentiment turns against the dollar.

As for the United States, although inflation has jumped, the Fed continues to dismiss the price rises as “transitory” even if it might now appear to be at least considering whether to start tapering its own asset purchase programme.

History shows that US inflation worries can turn foreign exchanges against the dollar.

In the 1970s, the dollar came under multi-year pressure as markets became unnerved when it appeared the Fed was “soft” on soaring US inflation. The dollar then rallied hard in the years after Paul Volcker’s 1979 appointment as Fed chief. The Volcker-led Fed crushed inflation as it raised the Fed Funds rate as high as 20 per cent in 1981. The early 1980s saw the US dollar soar.

This is not the 1970s, but the risk remains that the currency markets might start to doubt the current Fed leadership’s willingness to address rising US prices, especially when some other central banks are already tightening monetary policy.

But let’s not leave the late 1970s and early 1980s just yet, because the fall and then the rise of the US dollar in those years helped create the situation where Hongkongers in 2021 still have a vested interest in how the dollar performs.

By 1983, the floating Hong Kong dollar was pressured amid concerns about Sino-British negotiations on the post-1997 settlement for the city. That weakness was exacerbated by broad US dollar strength as the currency market’s Volcker-derived love affair with the dollar continued.

The Hong Kong dollar began 1983 at 6.5 to the US dollar but plummeted to 9.6 by September, triggering widespread local unease and causing strains in parts of Hong Kong’s banking system.

Hong Kong’s then financial secretary, John Bremridge, resolved the issue on October 17, 1983, replacing the Hong Kong dollar’s float versus the US currency with the linked exchange system that pegged the Hong Kong dollar at 7.8 to the US dollar. This arrangement was then amended in 2005 to allow Hong Kong’s currency to trade between 7.75 and 7.85 to the US dollar.

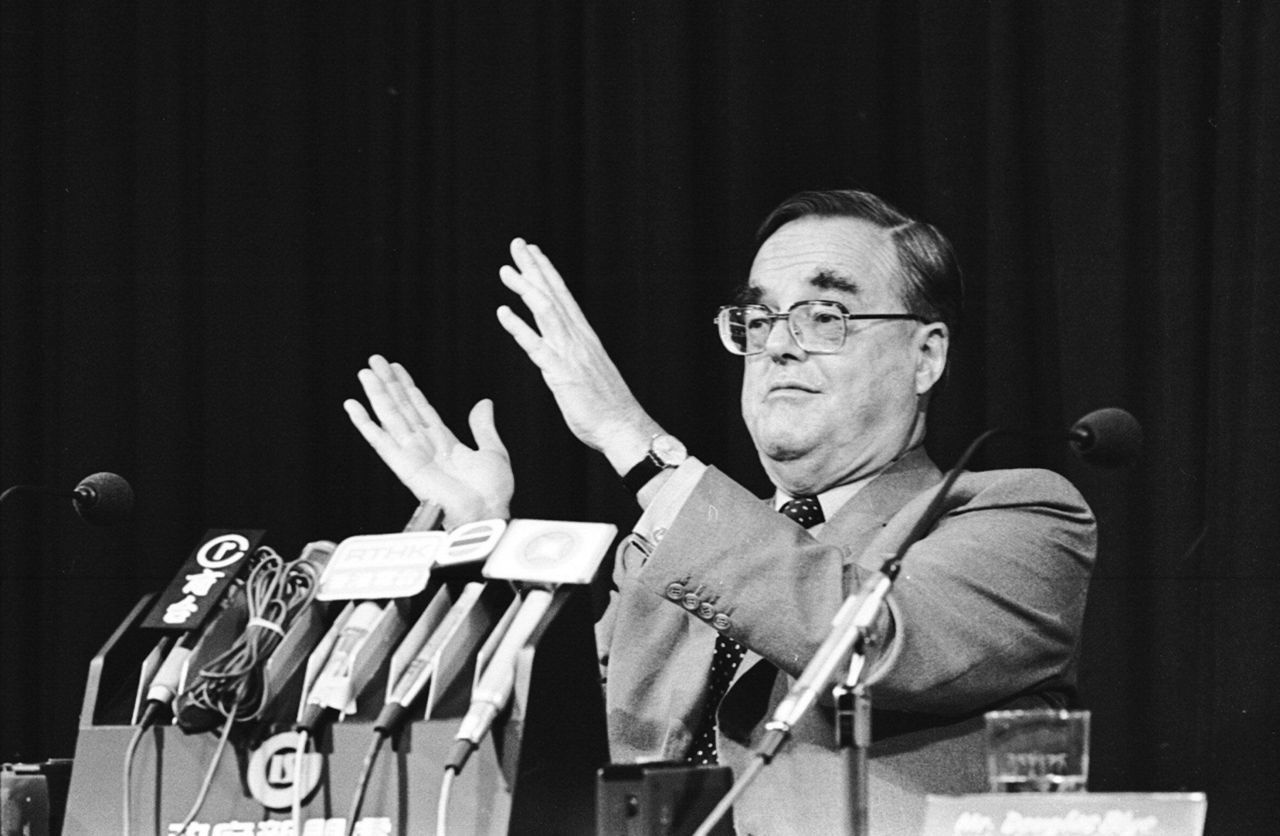

Financial secretary John Bremridge announces the pegging of the Hong Kong dollar at 7.8 to the US dollar, in October 1983.

Financial secretary John Bremridge announces the pegging of the Hong Kong dollar at 7.8 to the US dollar, in October 1983.

The legacy of this is that when the US dollar dives on the foreign exchanges, the Hong Kong dollar inevitably gets dragged down versus non-US currencies.

A reoccurrence of such a chain of events is a distinct possibility. Currency market sentiment may well turn against the US dollar if the Fed continues to ignore the US inflation data.