Hong Kong News

What Hong Kong can learn from Frank Gehry on managing mega projects

Delays and going over budget are the twin evils that haunt almost every Hong Kong government construction project. From the Sha Tin-Central rail link to the West Kowloon Cultural District and the Kai Tak Sports Park, we are accustomed to postponed openings, additional funding requests or cost overruns. Rarely has a project finished on time and within budget.

Covid-19 delivered the perfect storm but there is only so much that we can blame the virus for. The Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge and the Guangzhou-Shenzhen-Hong Kong Express Rail, for example, were built well before the pandemic and both went over their budgets, opening in 2018 after delays of two and three years respectively. We should look beyond convenient excuses and examine why our projects rarely deliver as planned.

To be fair, this is not unique to our government projects. Oxford University professor Bent Flyvbjerg and his team studied more than 16,000 major building and infrastructural developments around the world and found that 99.5 per cent of the projects failed to deliver on time, on budget and to achieve their objectives.

The general public might ask, are these projects not handled by experienced, well-compensated professionals? How do these so-called professionals and experts not learn to avoid the same mistakes?

Most private projects are developed using bank loans, which are costly, especially after recent interest rate increases. So owners want their projects built in the shortest time and to start operating as early as possible.

Often, such requirements are prerequisites in the lending terms and conditions, as lenders have every interest in the project quickly generating revenues for repayment. This often results in very tight – sometimes unreasonable – project timelines with no slack or room for failure.

Also, competitive construction contracts are often awarded to the lowest bid even as contractors try to outbid one another to land the tender – often without much of a profit margin but betting on future claims to make a profit. Thus, projects are often awarded within budget only for costs to run out of control.

Most of the time, consultants are no help either. From designers to engineers, project managers to quantity surveyors, we want to support the project owner, singing the same tune and painting an ideal picture, because doing otherwise might call our competence and credibility into question. How many consultants dare to tell their clients their expectations are unrealistic and unachievable?

Unfortunately, Murphy’s Law always seems to apply: anything that can go wrong will go wrong. We get used to sitting in uncomfortable chairs while the project owner screams about delays and cost overruns.

This has become the industry norm because we do not confront the reality that too many factors – from change of design to material lead times, fabrication challenges to logistics hiccups and site condition deviations – can derail progress.

The West Kowloon Cultural District seen at night in October 2021.

The West Kowloon Cultural District seen at night in October 2021.

More than 25 years after the Guggenheim Museum opened in Bilbao, Spain, Harvard Business Review published an article on how the project’s architect, Frank Gehry, manages to deliver within schedule and on budget.

The museum was completed US$3 million below budget and within the planned six years. It also attracted more visitors than the projected 500,000 a year, drawing 4 million in the first three years.

When Gehry was asked how he is able to finish his projects on time and on budget, he simply said the people who know the design best should have more control – what he called “the organisation of the artist”.

In another words, when project goals and decisions are exclusively made by owners and lenders who are not necessarily familiar with the design details, they often proceed, as the article noted, “on the basis of undiscussed assumptions”, setting up for failure from the beginning.

Most architects are not in the same league as Gehry; they do not speak with his weight or take ownership of high-level decisions. While we have a duty to provide professional advice, it takes a competent and rational decision-maker to listen to the advice and adopt it.

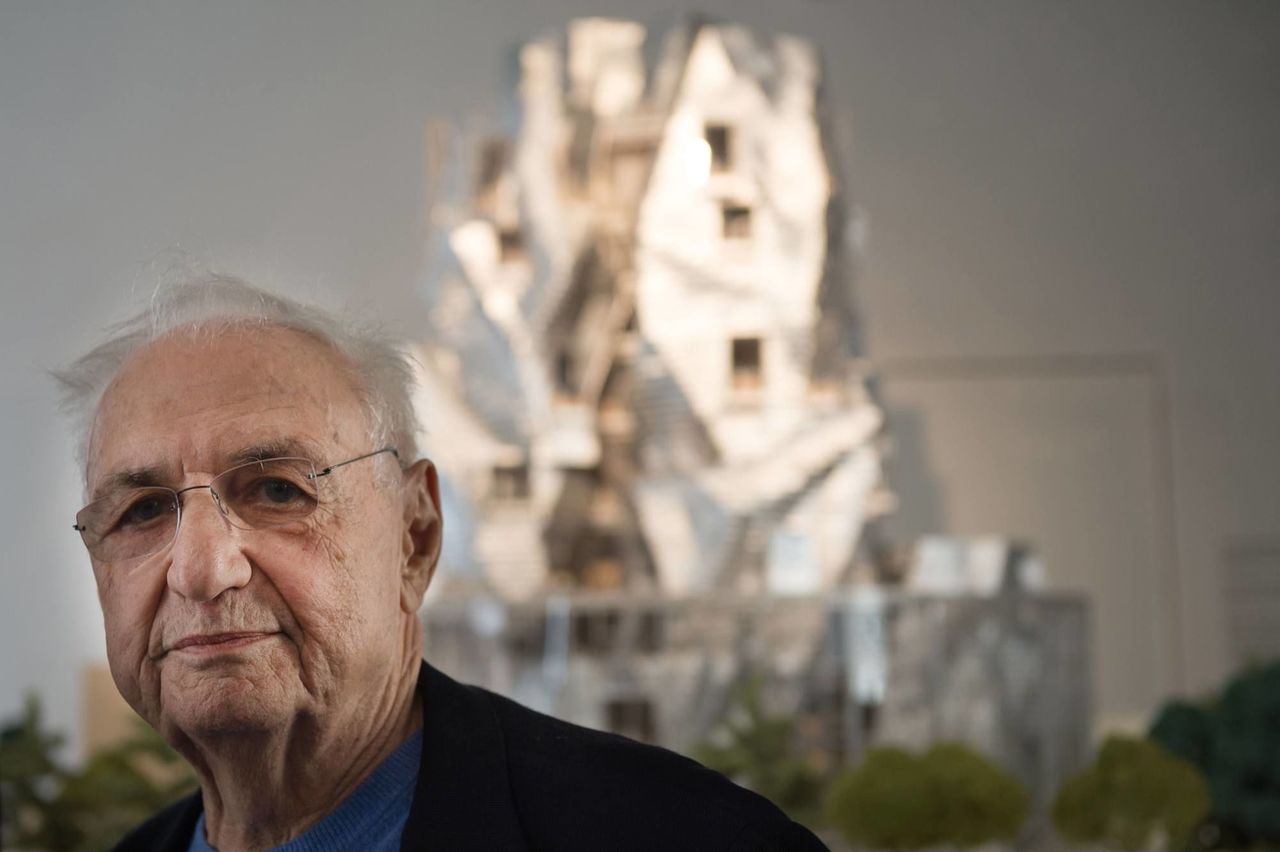

Pritzker Prize-winning Canadian-American architect Frank Gehry at a

press conference in front of a model of the Luma foundation he designed,

in Arles, southern France, on April 5, 2014.

Pritzker Prize-winning Canadian-American architect Frank Gehry at a

press conference in front of a model of the Luma foundation he designed,

in Arles, southern France, on April 5, 2014.

The reality is that one can hardly manage construction time and cost perfectly, but one can manage expectations by factoring in all the variables and potential risks, to present not only the best picture but also the worst-case scenario, and to preconceive of remedial measures to mitigate adversities. This is the art of project management that not many can master.

Unlike private developments, funding for most of our public projects is approved by the Legislative Council and its finance committee. There is no pressure from lenders or investors. But custodians should remember that the government is not the only “client” of public projects and that good governance keeps the public interest at its heart.

Project schedules and budget decisions demand sound professional input and rational justification. All the potential variables must be factored in so we do not put out, say, a HK$500 billion (US$63.7 billion) estimate for the reclamation of artificial islands one year, then another estimate of HK$580 billion several years later.

Taxpayers and stakeholders do not need a rosy picture or overhyped rhetoric. We would rather know the realistic completion dates and costs presented by competent individuals who aim for their projects to be among the 0.5 per cent that meet all targets and goals.