Hong Kong News

Rise of nano flats in Hong Kong has led to fall in living standards

Hong Kong private developers have built more than 8,500 nano flats that were each sold for millions of dollars over the past decade, according to a research group, which called for the government to impose a minimum size requirement on homes to improve living standards.

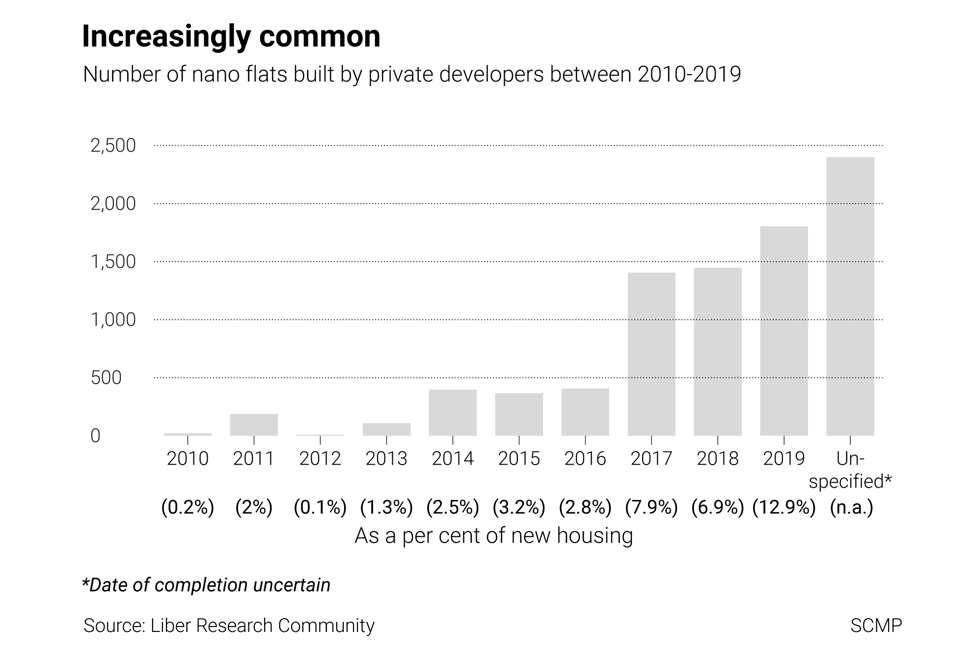

The supply of such flats – defined by the group Liber Research Community as those not bigger than 260 sq ft – has been on the rise. Production in 2019 made up 13 per cent of the total private housing supply that year.

In a new report, Liber, a civic group that focuses on housing and land issues, argued that government policies were to blame for the increase in nano flats, and it should follow overseas examples such as Singapore and Britain to discourage the construction of shoebox homes.

“The government has been compressing flat size as a solution to [land] shortages regardless of the corresponding worsening living standards,” Liber researcher Neon Yiu Ching-hei said. “This has led to a proliferation of tiny, or nano, flats, branded as ‘affordable’ homes in the market.”

The government’s task force on land supply, which steered a citywide debate on ways to source land in 2018, only focused on the quantitative demand and ignored home size and living quality, Chan Kim-ching, also from Liber, added.

The group argued that a former policy that imposed a minimum number of flats on land sales to encourage the construction of smaller homes, and relaxed building rules for windowless bathrooms and open kitchens, also had a part to play.

Hong Kong is one of the world’s least affordable housing markets. It would take 20.8 years, on average, to save enough money to buy a home in the city, according to the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey published last year.

For its research, Liber set the line for nano flats at 260 sq ft, taking reference from the Urban Renewal Authority’s minimum size requirement on project bidders before September 2018.

Based on the records of the Buildings Department and Lands Department and developers’ sales brochures, the group found 8,550 nano flats were constructed between 2010 and 2019, located in 96 projects.

More than half of them were built in the past four years, with 2019 seeing the most, at 1,805.

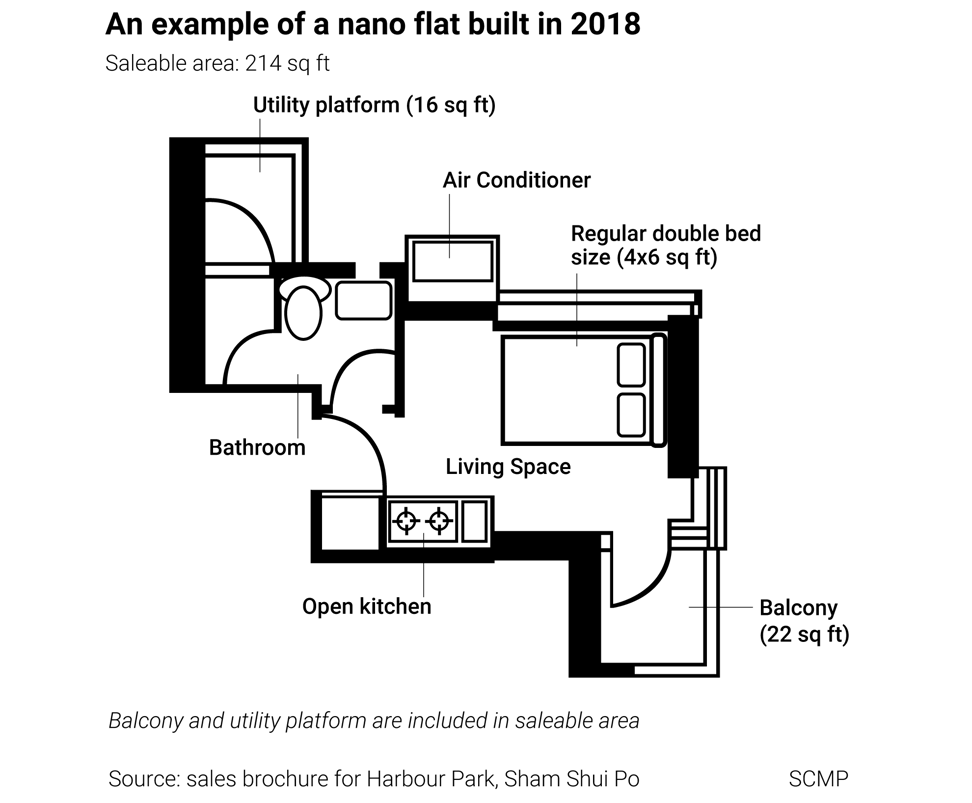

No nano flats have both a walled kitchen and a bedroom. About 70 per cent of the flats come with a “dark toilet”, a windowless bathroom that uses a mechanical system to bring in fresh air.

The set-up is allowed under a building rule relaxed in 2000, but the Institute of Surveyors recently noted that maintenance of such ventilation systems had often been neglected, posing sanitation risks.

More than 80 per cent of these tiny flats also have balconies, utility platforms or curtain walls that account for about 10 per cent of the saleable area on average.

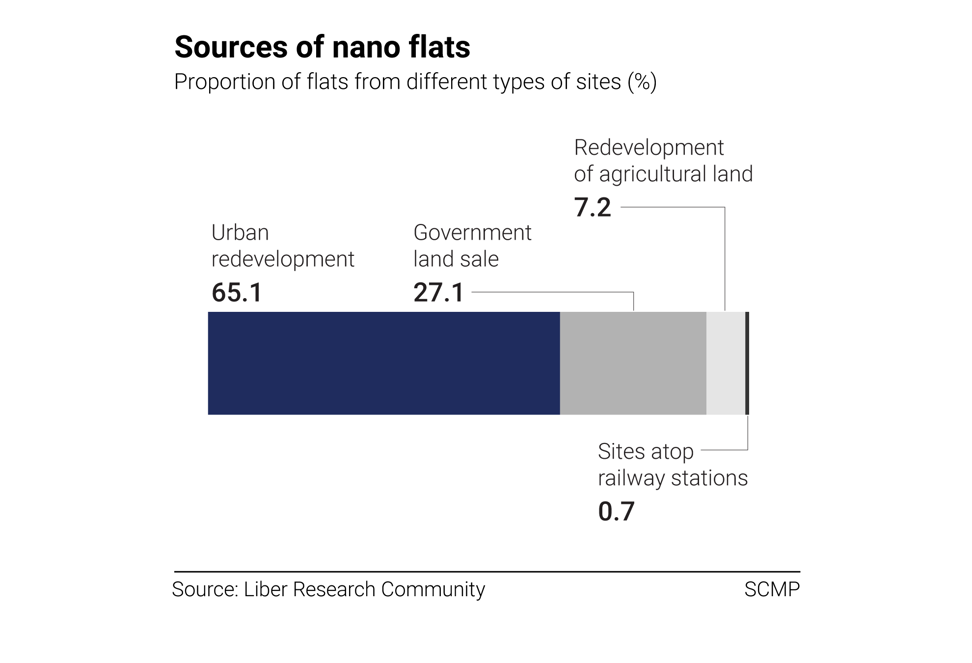

Some 65 per cent of the flats came from private redevelopment sites in old urban areas, while the rest were from government land sales. Henderson Land Development was responsible for producing the most nano flats – 2,858 of them, accounting for 33.4 per cent of the total.

Henderson said the company provided flats of varying sizes to cater to the needs of different homebuyers. “We noted that … there is a certain demand from small families and young aspirant homeowners. The company takes care in designing and building small units and strives to improve living quality through clubhouses, gyms and other leisure activities,” a representative said, adding that the company’s business strategy would be adjusted in response to changes in the market.

Liber, meanwhile, said nano flats provided no privacy and posed health concerns.

It suggested the government introduce a minimum size requirement in land sales and in a law facilitating private redevelopment of urban sites, and that it do away with certain building rules, such as those allowing “dark toilets”.

It also called for a halt to rules that lead to features such as balconies and utility platforms being included in nano flats’ saleable floor area, resulting in buyers paying tens of thousands of dollars for square footage that contributes little to the actual living space of their already-tiny homes.

Liber cited the example of Singapore, which changed a building rule in 2018 to decrease the production of tiny flats in the private sector. Under the new rule, the maximum number of homes allowed in a development outside the central area is arrived at by dividing the proposed building’s gross floor area by 85 square metres. The old formula divided the gross floor area by 70 square metres.

In response to the call for size regulations, the Development Bureau said the current priority was to increase housing supply to satisfy residents’ basic needs, and that society could explore a standard for living spaces only in the long run, when the land shortage had eased.

The government did not have plans to impose size requirements on land sales, considering the different characteristics of each site and changes in market demand over time, it said. It would review the rules for building design in due course, taking into account industry feedback.

Lau Chun-kong, a former president of the Institute of Surveyors, said the government was to blame for the rise of nano flats.

He said high market prices, due to land shortage, had led to developers building smaller flats, as buyers could not afford big ones. In addition, stamp duties and the tightening of mortgage borrowing discouraged holders of small flats in the second-hand market from trading up to bigger homes. So new aspirant homeowners could only flock to the first-hand market for small flats, driving up the demand.

“Nano flats are a market response to high prices and government intervention,” he said. “They’ll be around until land and housing supply is abundant.”

Lau said he did not object to imposing a minimum size requirement as an interim measure.

Lawrence Poon Wing-cheung, a Town Planning Board member, agreed there should be a minimum flat size, say around 250 sq ft. “There have been flats that are unreasonably small, below 200 sq ft. This should not be allowed, but the standard should not be set too high, considering what people can afford, and that the demand for small homes does exist.”

Poon said he believed there would be fewer nano flats when the supply of subsidised housing increased.

But he disagreed with Lau that the market-cooling measures were to blame for the rise of tiny flats, because buyers in the primary market were often a different group from those in the second-hand market, with the former looking for mortgage concessions from developers.