Hong Kong News

No switching off Hong Kong’s bright city lights as shops replace old neon signs

When Andrew Chui Shek-on was ordered to remove the 42-year-old neon signboard hanging over the Tai Ping Koon Restaurant in Tsim Sha Tsui, he could have taken it down and left the storefront barren.

Instead, the fifth-generation owner of the chain of four Chinese eateries famous for its Swiss chicken wings and giant souffles replaced it with a new one.

For him, the neon sign was an important part of the 163-year-old restaurant’s history.

“It’s not just a sign,” Chui said. “It represents the culture of Hong Kong.”

Tai Ping Koon Restaurant’s neon sign being removed from their branch in Tsim Sha Tsui.

Tai Ping Koon Restaurant’s neon sign being removed from their branch in Tsim Sha Tsui.

Like Tai Ping Koon, businesses such as Nam Cheong Pawn Shop in Sham Shui Po and Hong Zhou Restaurant in Wan Chai have put up new neon signs this year that meet current rules.

Ken Fung Tat-wai, co-founder of signboard preservation group @streetsignhk, said: “Over the past few years we’ve seen more shops choosing to rebuild their signs.”

Since 2017, he and fellow architect Kevin Mak King-huai have used their group to promote signboard culture, while also helping businesses preserve and rebuild their traditional signs.

“Even in 2017, people still saw signboards more as a hazard than a piece of Hong Kong’s heritage,” Fung said.

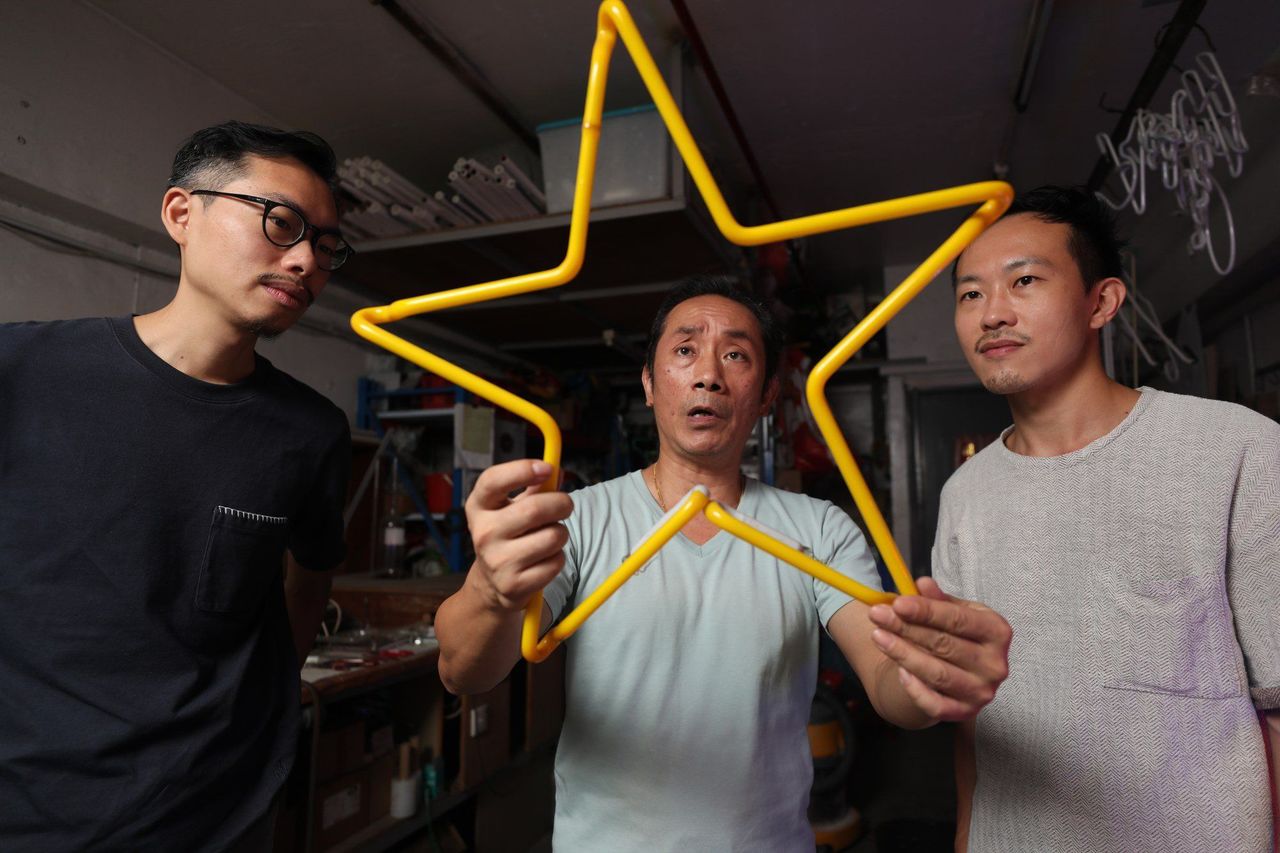

Co-founders of @streetsignhk Ken Fung (left) and Kevin Mak (right) with Wu Chi-Kai at Wu’s studio in Tai Wo Hau.

Co-founders of @streetsignhk Ken Fung (left) and Kevin Mak (right) with Wu Chi-Kai at Wu’s studio in Tai Wo Hau.

The disappearance of Hong Kong’s traditional neon sign boards, following the rise of LED technology and tightening signboard regulations, received renewed attention this week with the release of the film A Light Never Goes Out.

Taiwanese actress Sylvia Chang stars as a grieving widow who takes up her late husband’s trade of making neon signs. She is a nominee for Best Actress at the 41st Hong Kong Film Awards on Sunday, having already won an accolade for the role at Taiwan’s Golden Horse last year.

Sylvia Chang in a scene from ‘A Light Never Goes Out’.

Sylvia Chang in a scene from ‘A Light Never Goes Out’.

In Hong Kong, public safety concerns grew in the 2000s after incidents of ageing signboards falling on pedestrians.

By 2010, the government had introduced a dedicated signboard control unit and retroactively rendered all existing signboards illegal unless they complied with new building standards on size and placement.

The Buildings Department, which is responsible for enforcing the rules, said it did not keep track of neon signboards specifically, but some groups estimate that there are only a few hundred left.

Businesses can register under the Signboard Validation Scheme to avoid having their signs removed, but since its introduction in 2013, only 410 applications have been approved.

The department said an average of about 3,300 signboards had been “removed or replaced” annually between 2018 and last year.

Fung said cost remained the biggest hurdle stopping more businesses from installing new neon signs.

These signs require a skilled master to build them, and there are only around eight left in the city. Businesses also need to spend thousands of dollars a year on maintenance, as the glass tubes are easily damaged by bad weather and falling objects.

But even LED signs, which are considerably cheaper and more energy efficient, are too expensive for many small businesses suffering from the city’s economic downturn over the past few years, Fung said.

“It’s already a big cost for a small business to take down a sign,” he said. “So most will not think of installing a new one.”

Owner of Koon Nam Wah Bridal Winnie Lam.

Owner of Koon Nam Wah Bridal Winnie Lam.

Winnie Lam Wing-yee, owner of Koon Nam Wah Bridal, said she paid more than HK$300,000 (US$38,216) to replace two large neon signs taken down from her Kowloon store last August.

She said she was heartbroken to receive a final warning from the Buildings Department to remove the signs which were first installed when her father ran the business nearly 50 years ago.

“I wanted to keep them up as long as possible,” Lam said.

But owners who do not remove their signs face up to a year in jail or a fine of up to HK$200,000.

Lam complied with the order but immediately started planning for a new sign that was smaller and within the rules.

“I still want to keep the tradition alive,” she said. “It’s something you can only see in Hong Kong.”

Brian Kwok Sze-hang, an associate professor at the design school of Polytechnic University, said neon had a symbolic association with Hong Kong’s economic boom period of the 1980s and 1990s, particularly among a younger generation becoming increasingly interested in the craft.

“Neon signs represent the prosperity of the city,” he said.

He said retaining the signs while obeying current rules could still convey the “high level of craftsmanship” involved and reflect a shop’s deep connection with Hong Kong.

Andrew Chui, owner of Tai Ping Koon, at his Yau Ma Tei branch.

Andrew Chui, owner of Tai Ping Koon, at his Yau Ma Tei branch.

Tai Ping Koon Restaurant’s Chui said he was already preparing to install another new neon signboard to replace the 60-year-old sign at his Yau Ma Tei branch.

Now 61, he said he was looking forward to the day when his son Anson, 13, took over the business and inherited the new neon signs.

“I want him to understand that the sign has so much meaning for us, it’s a part of our family’s legacy,” he said.

“When the old sign is torn down, it will feel like the end of an era, but when the new sign goes up, it represents a new era for him.”