Hong Kong News

Meet the transnationals: They moved to Canada but never really left Hong Kong

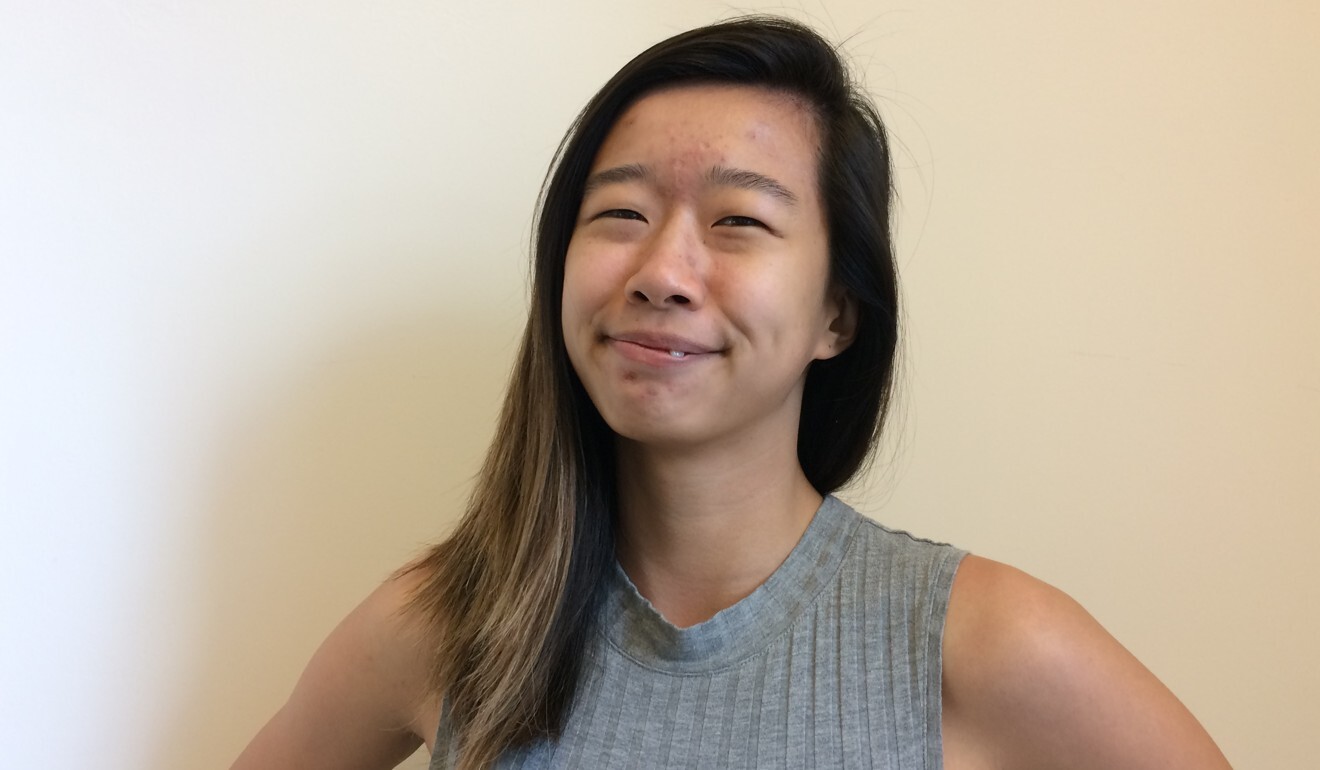

Cherie Wong was utterly consumed by the protest movement that swept Hong Kong last summer.

“I didn’t sleep properly for days, for weeks, really,” she said. She watched the protests obsessively, then became an activist herself. Wong, 24, tried to discuss her beliefs with older family members who included former members of the Hong Kong Police Force.

“It ended up in conflict, it was awkward,” she said. But her activities were cheered by her grandmother, in her mid-80s, who was “incredibly pro-protester. We’d just go into a private chat to talk about it.”

But Wong, a freelance writer and policy researcher, was not in Hong Kong. She was more than 12,000km away in Ottawa, Canada, watching events unfold on her smartphone.

“I would fall asleep watching a live stream, with my phone in my hand. I would wake up and the live stream would still be going,” she said.

Guy Ho in Hong Kong in the early 1970s. He moved to Canada in 1977, back to Hong Kong in 2004, then returned to Canada in 2015. Photo: HandoutGuy Ho in Hong Kong in the early 1970s. He moved to Canada in 1977, back to Hong Kong in 2004, then returned to Canada in 2015. Photo: Handout

Guy Ho in Hong Kong in the early 1970s. He moved to Canada in 1977, back to Hong Kong in 2004, then returned to Canada in 2015. Photo: Handout

Cherie Wong was utterly consumed by the protest movement that swept Hong Kong last summer.

“I didn’t sleep properly for days, for weeks, really,” she said. She watched the protests obsessively, then became an activist herself. Wong, 24, tried to discuss her beliefs with older family members who included former members of the Hong Kong Police Force.

“It ended up in conflict, it was awkward,” she said. But her activities were cheered by her grandmother, in her mid-80s, who was “incredibly pro-protester. We’d just go into a private chat to talk about it.”

But Wong, a freelance writer and policy researcher, was not in Hong Kong. She was more than 12,000km away in Ottawa, Canada, watching events unfold on her smartphone.

“I would fall asleep watching a live stream, with my phone in my hand. I would wake up and the live stream would still be going,” she said.

While the past year of turmoil in Hong Kong has rippled through diaspora communities around the world, it has been felt with particular intensity in Canada.

Protests over Beijing’s handling of the city continue regularly in Canada. Hong Kong activists were given a platform by a parliamentary committee which has spent eight months investigating Ottawa’s relationship with China. And clashes between rival camps supporting and opposed to the protest movement have spilled onto the streets of Vancouver and Toronto, vividly mirroring the conflict in Hong Kong.

Canada’s experience of Hong Kong’s year of tumult has been largely defined by the phenomenon of transnationalism, in which hundreds of thousands of immigrant Hongkongers and their children divide their lives and emotions between both places, sometimes alternating between the two over decades, in ways that are far less common among American Hongkongers.

Guy Ho, 58, an IT trainer, moved to Canada with his parents as a teenager in 1977. He returned to Hong Kong in 2004, then moved back to Canada in 2015. “I saw it coming. In every way. The whole environment was changing … this was not the Hong Kong I used to know,” said Ho of his most recent move.

Ho had participated in the “umbrella movement” protests in Hong Kong in 2014. After returning to Montreal, he resumed his political activity there, helping organise protests and other events about Hong Kong last August with his husband, fellow Hong Kong immigrant Henry Lam, 43, a translator and novelist.

Unlike traditional understandings of migration as a completion, transnationalism is a continuum of movement and behaviour. And it has extended to the children of Hong Kong immigrants, like Wong, with residency rights in both places.

Wong was born in York, Ontario, moved to Hong Kong at the age of two, then returned to Canada about a decade ago to complete her schooling. She said she connected with her Canadian identity at international school in Hong Kong – but after returning to Canada, she would describe her holidays to friends by saying, “guys I’m going home, and they’d say, ‘home to Ontario? No, home to Hong Kong.’”

Now she calls herself a Hongkonger Canadian.

“This place we live in – it’s not like we have one home. We have two homes,” said Wong.

Bouncing back and forth

The Hong Kong-Canada transnational experience has been forged by tax and immigration policies that created the densest populations of the Hong Kong diaspora in the Western world, and the largest community of foreign citizens in Hong Kong.

Although the number of Hong Kong-born people who live in the US and Canada are roughly similar, at more than 200,000 each, there are some 300,000 Canadians living in Hong Kong, mostly returnee migrants and their children, according to Global Affairs Canada. About 85,000 Americans are said by the US State Department to be living in Hong Kong.

This strong tendency towards transnationalism among Hong Kong Canadians boils down to differences in tax law, according to David Lesperance, a Canadian lawyer who has been involved with Hong Kong immigration for about 30 years.

American tax obligations follow US citizens for life. But Canadian citizens can declare tax non-residency and move back to Hong Kong, resuming careers there and paying its lower levels of tax.

“The United States is the only country in the world that also taxes you based on citizenship,” said Lesperance. “As a US citizen, you are a full US taxpayer … But in Canada, you can come in, get citizenship … become a [Canadian] non-resident for tax purposes, and then you can bounce back and forth until you’re going to retire in Canada.”

This is also possible for Hongkongers who immigrated elsewhere, such as Britain or Australia. But Canada became the most common choice because of early immigration policies that catered to middle-class and wealthy Hongkongers from the 1980s onwards, said Lesperance.

For comparison, there are 87,000 Hong Kong immigrants in Australia and 100,000 Australians in Hong Kong, according to the Australian consulate-general. In Britain, there are about 96,000 Hong Kong immigrants (the number of Britons in Hong Kong is unclear.)

Hong Kong-born Professor Leo Shin, convenor of the Hong Kong Studies Initiative at the University of British Columbia, said that “what distinguishes the Hong Kong-Canadian story is the sheer number of Hongkongers who left Hong Kong for Canada within a relatively short period.”

“Between 1982 and 1998, more than 350,000 Hongkongers became permanent residents of Canada, many of whom would eventually settle in major cities such as Vancouver and Toronto,” said Shin, 52, who landed in Canada with his parents on June 7, 1989, days after the Tiananmen Square crackdown.

The influx concentrated itself in Vancouver and Toronto in numbers unmatched in US cities or elsewhere in the western world. There are currently more than 100,000 Hong Kong-born people in greater Toronto alone, population 5.9 million. That exceeds the 96,000 Hong Kong immigrants in all of California – home to 40 million people.

Vancouver, meanwhile, is home to 71,000 Hong Kong-born people among a population of just 2.4 million.

“The large number of immigrants from Hong Kong or mainland China in cities such as Vancouver or Toronto is no doubt the main reason the turmoil in Hong Kong has had such resonance in such places,” said Shin.

Justin Tse is an assistant professor of humanities at Singapore Management University who has studied transnationalism among Hong Kong Canadians. He is the son of Hong Kong emigrant parents who moved to Canada in 1981, but he is a dual US-Canadian citizen – Tse was born in Vancouver but moved with his family to the San Francisco Bay area when he was an infant. Tse returned to Vancouver to study at UBC; he has never lived in Hong Kong.

Transnationalism, said Tse, is the notion that a migrant from one place to another establishes a “social field” between the two, blurring the distinction between past and present physical homes. “They operate simultaneously between the two places,” he said. “Whatever they do in their new place of residence has direct effects back home. There’s no difference between the home and destination countries because there is this social field involved.”

As a theory, transnationalism was born in the US. “But it’s interesting that this phenomenon is playing out much more in Canada,” said Tse.

Tse said that during his research on Hong Kong Canadian youth he was surprised that they thought of themselves as “very Canadian” even as they remained strongly attached to Hong Kong.

Cantonese-speaking institutions – churches and immigrant-service societies, for instance – meant there was no need to either assimilate into “white Canadianness” or “bloc Chineseness” while still thinking of themselves as Canadian.

Indeed, Tse said he was surprised to find that things he thought of as transnational, as an observing American, were understood by the interviewees to be expressions of Canadianness instead.

For instance, continuing to speak Cantonese was seen by some as an expression of Canadian identity: it differentiated them from the Americanness of the immigrant melting pot to the south.

“This was ‘we have a different narrative to the United States. We’re multicultural. We can keep our cultures’ [and] what I had parsed, as an American, as them maintaining Hong Kong transnational ties, [they thought] was actually them being exquisitely Canadian.”

In contrast, Tse’s own family in the US became beholden to “the burden of being Chinese-American”.

“Hong Kong for us was a place of nostalgia. We listened to Sam Hui. We watched TVB on KTSF Channel 26, we were living the Chinese-American life … But these ‘astronauts’? Their sensibilities were entirely different. They had actual familial transnational ties to Hong Kong: ‘Wait, have you moved? Have you not moved?’ and they were like ‘kind of both’.”

“Astronaut” is a term referring to Asian transnational family arrangements, in which an immigrant breadwinner returns to their homeland while supporting a spouse and children in the new country.

“For them, maintaining actual ties to Hong Kong … was very important to them. Whereas it wasn’t important to our family. We didn’t even call people in Hong Kong, for example,” said Tse.

Back in Hong Kong, the Canadian transnational community may be huge, but in many ways it is invisible, since it consists mostly of Hong Kong-born dual citizens and their children.

Hong Kong’s statisticians do not even acknowledge the group’s existence because dual citizenship is not recognised under China’s nationality law. According to the 2006 Hong Kong census, there were only 11,976 Canadians in the city; by 2016, Canadians did not even make the top 10 of foreign nationals.

But the Canadian population of Hong Kong is thought to be roughly the same as that of Halifax, Nova Scotia. If they were a city, they would be Canada’s 15th largest.

In 2011, the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada released a “conservative” estimate that there were 295,930 Canadians in Hong Kong. Sixty-seven per cent were born in Hong Kong and just 16 per cent in Canada.

But their continuing connections to Canada were clear: 64 per cent had immediate family members living there. And 62 per cent were considering returning to live in Canada themselves.

Transnational ‘guilt’

Ho was one who did just that. He returned to Canada in 2015 after marrying Lam on a visit to Vancouver in 2011.

Ho demurred when asked if he felt more at home in Hong Kong or Canada. “With all the travelling I’ve done, I can feel at home anywhere,” he said.

“There are things I love about Hong Kong, and things I appreciate about Canada … In Hong Kong, the people, my family, friends, of course the food, the unique culture.

“In Canada, the fresh air. The space. The friendly Canadians.” And as gay men, Ho and Lam, who recently moved from Montreal to Vancouver, are recognised in Canada as a married couple, unlike in Hong Kong “where we are ‘just friends’.”

In a 2004 study of return migration among Hong Kong Canadians, geographers David Ley and Audrey Kobayashi wrote that “transnationalism invokes a travel plan that is continuous not finite. Immigrants never quite arrive at their destination because they never quite leave home.”

But the limits to that process are now being tested for some in an unexpected way, by Hong Kong’s new national security law.

Wong, Ho and Lam all said they had no plans to return to Hong Kong, to live or visit, citing fears about the law.

Wong is one of the founders of an activist group called Alliance Canada Hong Kong. She testified on August 11 at the House of Commons committee on Canada-China relations, which was launched in December. She told MPs of her fears about the extraterritorial reach of the law, which criminalises secession, subversion and collusion with foreign powers, not just on Hong Kong soil but anywhere in the world.

“I’m not going to go back to Hong Kong, not until Hong Kong is liberated, whatever that means … I don’t think I would be safe to go back,” she told the Post.

Ho and Lam agreed; this time it feels like Canada is for keeps, said Ho.

Instead they watch Hong Kong from afar. For Lam in particular, it has been an emotionally draining experience: “I was in Canada but my heart was in Hong Kong.”

Ho said he feared that his husband “somehow feels guilty, feels responsible … other Hongkongers when they see Henry write about supporting democracy, they would say ‘you’re not even in Hong Kong, you don’t have a say’. That is very, very hard to take.”

Tse said he suspected that transnationalism could lead some in Canada to “overdetermine” their Hongkongness, amid the intense emotions stirred by the protest movement. “You only have one body, right? You can’t physically be in two places at once. You aren’t physically pulling on a gas mask,” he said.

“Oftentimes when we talk about transnationalism and its simultaneities, we forget media isn’t as developed as Star Trek. You’re not teleporting to Hong Kong. You’re sitting in front of a screen and wishing you were there.”

He added: “Anecdotally, people have told me they feel guilty: ‘my God, I’m in a place of such privilege compared to what’s going on there [in Hong Kong]’.”

Wong echoed the sentiment. She said her activism was born from a “duty to Hong Kong” that demanded she employ her rights as a Canadian citizen, that she felt friends in Hong Kong did not have. “I can speak my mind and the government won’t come after me. I can say ‘Hong Kong needs democracy. Hong Kong needs to be free’ and I can say these words without consequences in Canada.”

But she said she misses Hong Kong, and “not as some kind of fantasy world”. She misses the cold metal seats of the MTR and the rush-hour “squish”, eating out at 2am, even “the dirty air, that smell”.

“When I was back to Hong Kong, I’d go to a specific stall, and the owner would remember me and say, ‘how is life in Canada?’,” Wong said.

“They’d know that I came back every few years and would say, ‘oh, when do you leave? Let me give you a little extra. Just in case you don’t come back to see me again’.”