Hong Kong News

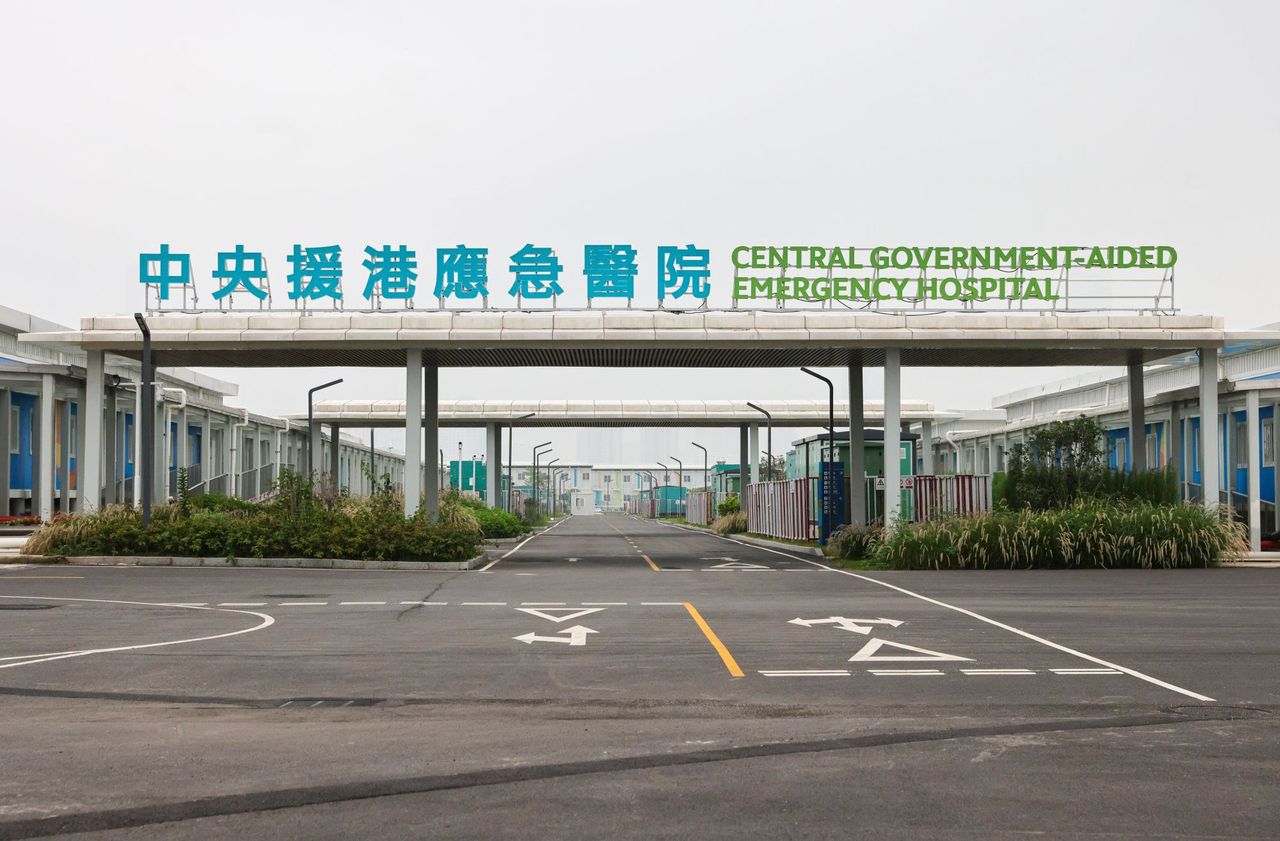

Makeshift Covid hospital in Hong Kong to be used for radiology services

A makeshift Covid-19 hospital that has sat idle for a year in Hong Kong is expected to provide diagnostic radiology services to 7,000 patients annually under a pilot scheme.

From Wednesday, patients who meet certain criteria can access computerised axial tomography (CAT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) services at the hospital in the Lok Ma Chau Loop near the mainland China border under the pilot programme.

The makeshift hospital was built last April with Beijing’s help and had been left idle until the Hong Kong government handed it to the Hospital Authority in January this year.

The makeshift hospital was built with Beijing’s help.

The makeshift hospital was built with Beijing’s help.

Patients currently receive diagnostic radiology services at public hospitals, which is deemed as not ideal.

“Conflicts [of time] often happen when routine cases and emergency patients are put in the same queue at public hospitals, the routine cases may also feel uncomfortable when mixed with trauma patients,” said Dr Paul Lee Sing-fun, chairman of the authority’s coordinating committee in radiology.

“If we can systematically divert those patients to ambulatory centres, the whole process will be smoother and more efficient.

“And the availability of the makeshift hospital provided us with a good opportunity to develop such services.”

He said the hospital offered abundant space – as well as three CAT scanners and one MRI machine – a condition that could not be found in other facilities and prevented the authority from forming an ambulatory centre for radiology services.

Mak Tsz-wai, a diagnostic radiographer at North District Hospital who is among the first batch of 20 healthcare workers at the facility, said one advanced CAT scanner there could acquire a cardiac image in a second, which was helpful for patients who had difficulty holding their breath for the process.

The scanner could also reduce radiation exposure by up to 30 per cent, he added, and all the machines were designed to reduce the risk of transmission.

Patients aged 12 to 80 in stable condition and able to travel and who have waited for the service for a certain length of time are eligible for the scheme. Those attending public hospitals in the New Territories will be referred first.

Routine cases that have waited for 18 months, and priority two cases that have been in the queue for eight months, which Lee said accounted for 20 per cent of the total patients, would be invited to use the service.

The facility will be able to handle thousands of patients annually.

The facility will be able to handle thousands of patients annually.

According to authority figures, the median waiting time for CAT scans across all hospitals for priority two and routine cases stood at 35 and 79 weeks, respectively, and for MRI scans 34 and 80 weeks, as of December last year.

The new service would be subsequently made available to patients from across Hong Kong from July.

Nine MRI scan sessions and 19 for CAT scans will be offered each weekday, but capacity could be further increased with sufficient demand and manpower.

Considering the remote location of the facility, eight shuttle bus runs would be provided every day to ferry patients and their carers from Sheung Shui MTR station to the makeshift hospital. The ride is about 20 minutes.

Earlier this year, Deputy Financial Secretary Michael Wong Wai-lun was tasked by Chief Executive John Lee Ka-chiu to review the future use of community quarantine and treatment facilities that had been built for the Covid-19 pandemic.

But even with the use of the diagnostic imaging machines, most of the makeshift hospital, including intensive care units and medical wards, remains idle.

Dr Sin Ngai-chuen, clinical stream coordinator of hospitals in New Territories East, said they did not have a definite road map to expand the services but were looking into various possibilities.

Dr Sin Ngai-chuen (left) and Dr Paul Lee pose for a photo in front of a CAT scan machine.

Dr Sin Ngai-chuen (left) and Dr Paul Lee pose for a photo in front of a CAT scan machine.

The pilot ambulatory diagnostic radiology service comes amid a serious manpower crunch at public hospitals. An 8.9 per cent attrition rate was recorded for diagnostic radiographers and radiation therapists in 2022, 4.6 percentage points higher than in the year 2020-21.

Sin dismissed such concerns, saying existing radiology services would not be affected.

“We strived to optimise the use of manpower, with radiographers being the core of the team, they are also willing to work extra hours to prevent services from being affected, that’s why we applied for a special honorarium [for them],” he said.

The authority would also hire part-timers and retirees to strengthen manpower, he added.

The pilot scheme will be subject to an annual review and is expected to run for three years before discussions on whether to regularise the services.

Patients’ rights advocate Tim Pang Hung-cheong, from the Society for Community Organisation, said the pilot scheme could help shorten waiting times for imaging services, but the change would not be significant.

“The biggest problem now is not about hardware but [manpower],” Pang said, noting the public sector was already suffering from a shortage of radiologists and radiographers.

“If some of the existing staff are allocated to the loop facility, it will further strain the tense manpower in public hospitals,” he said.

Pang said that unless there was an overall increase in manpower it would be difficult to make use of other facilities in the hospital.

“Can the hospital be outsourced to private medical groups to operate … or cooperate with healthcare facilities in the Greater Bay Area?” he said.