Hong Kong News

Mainland Chinese academics outnumber locals at Hong Kong universities for first time

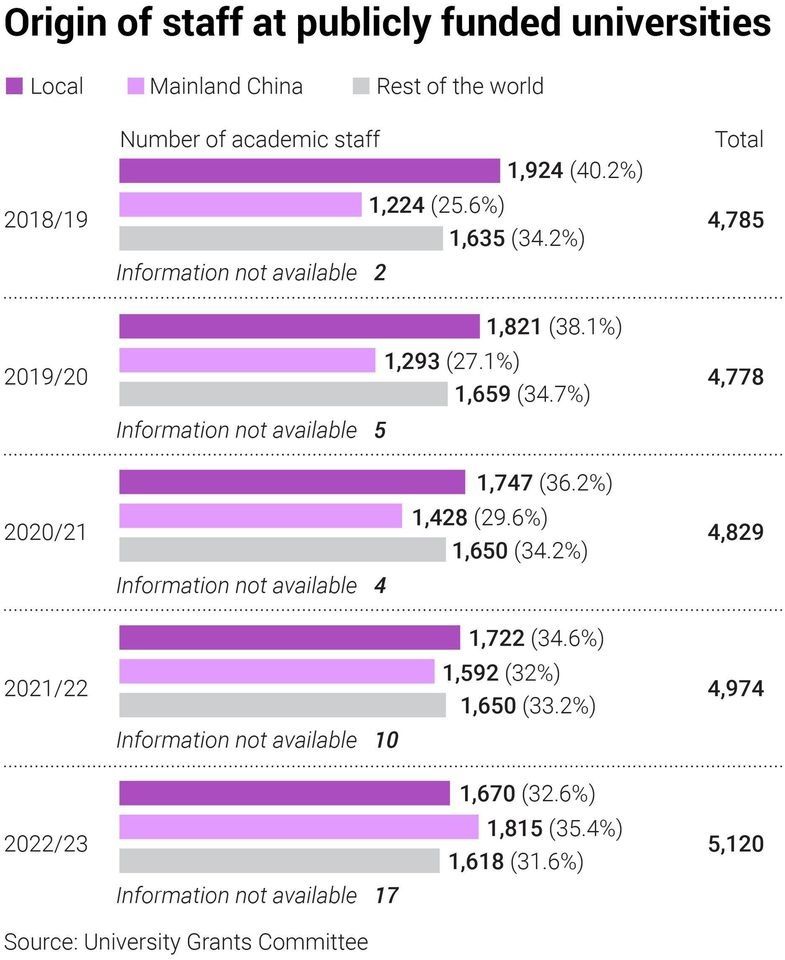

For the first time, academics of mainland Chinese origin outnumber locals among the 5,120 employed by Hong Kong’s eight publicly funded universities.

Their number reached 1,815 in the current academic year, making up the biggest proportion of academics in the city at 35 per cent. The figure was up from 1,224 five years ago.

A quarter of the mainlanders work in science faculties, more than a fifth are in engineering and technology departments and a fifth are in business and management.

The number of locals fell from 1,924 to 1,670 and their proportion shrank from two-fifths to a third over the same period, according to figures from the University Grants Committee.

Those from the rest of the world stayed about the same, declining from 34 to 32 per cent of the total.

While the universities said they had rigorous processes for hiring academic staff, some scholars said mainlanders were attracted to Hong Kong by good pay and prospects, as well as the availability of generous research grants.

Mainlanders now outnumber locals at four universities – the University of Science and Technology (HKUST), City University, Lingnan University and the University of Hong Kong (HKU).

Their presence is strongest at HKUST, where 48 per cent of the academic staff is from the mainland, and only 15 per cent from Hong Kong.

A spokeswoman said the university was an equal opportunities employer with established appointment guidelines and procedures for recruiting faculty, and took into account candidates’ academic profiles, achievements and potential.

A spokeswoman for HKU, where mainlanders account for 34 per cent and locals 29 per cent of academic staff, said it had stringent requirements too.

“Each case is evaluated on its individual merits. The university is committed to equality, ethics, inclusivity, diversity and transparency,” she said.

Polytechnic University (PolyU) has also seen a dramatic change. The mainlanders’ presence expanded from under a fifth five years ago to almost two-fifths. Locals, who used to account for more than half, are now ahead by only 1 percentage point.

Among the mainland scholars who moved to Hong Kong is Professor of Mechanical Engineering Chen Qingyan, 64, who took up his position as director of PolyU’s Academy for Interdisciplinary Research in 2021.

A graduate of Beijing’s Tsinghua University, he obtained his doctorate from Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands and worked as a research scientist in Switzerland before moving to the United States.

He was an associate professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and then spent nearly two decades at Purdue University in Indiana.

“The research environment in Hong Kong is similar to that in Western societies, but Hong Kong has more resources,” he said. “The government is putting in more research money to improve conditions in Hong Kong.”

He said the trend of universities hiring more mainlanders was happening worldwide, not only in Hong Kong, as their quality had improved.

“Thirty years ago, mainland China had no money for research. No matter how intelligent you were, without money, you could not do much,” he said. “Now, mainland China has a lot of research funds and the research level is getting better and better.”

The University of Science and Technology’s campus in Sai Kung.

The University of Science and Technology’s campus in Sai Kung.

He did not find it “weird” that mainland academics now outnumbered locals in the city’s universities and pointed out that many local scholars were also working overseas.

“I think it is very good for academic exchange, and in research we are always exchanging ideas,” he said. “Every country is different and when you work with scholars of different backgrounds, you’ll find out new things.”

Political scientist Ma Ngok, a Hongkonger and an associate professor at Chinese University, said the pool of mainland academics was huge, particularly in science and technology.

“For the mainland scholars, Hong Kong is not only a freer place, but also quite an attractive place offering better salary than mainland institutions,” he said. “Hong Kong is also a place where they can adapt easily.

Ma added that Hong Kong’s talent pool was shrinking as more local scholars tended to further their studies overseas and settle elsewhere.

“I would describe the current composition of academic staff as a very natural one,” he said.

Samson Yuen Wai-hei, an associate professor at Baptist University’s department of government and international studies, brushed aside the suggestion that the presence of more mainland scholars meant there would be fewer research projects on Hong Kong issues.

He said the direction of research in higher education was driven mainly by the allocation of funding, and the current focus on science and technology reflected government policy.

But he added that research on Hong Kong issues was actually “growing exponentially, not shrinking”.

“Whether research on local affairs continues hinges on whether the topics are still relevant in society, such as local elections and social movements, rather than the scholar’s place of origin,” he said.

HKU undergraduate representative Casey Chik Yau-hong said he did not think the rising number of mainland academics had a great impact on teaching and learning.

A third-year student of government and laws, he said it was natural for mainlanders to take the lead in the postgraduate sector which was dominated by students from over the border.

He said he looked forward to HKU having academics of diverse backgrounds.

“But it is natural that the local, mainland and overseas students get along with professors of the same background,” he said.