Hong Kong News

Law on blank ballots, polls boycott full of pitfalls, Hong Kong experts warn

Legal scholars have warned of “real constitutional problems” in new legislation proposed by Hong Kong authorities that would make it a criminal offence for people to encourage voters to boycott elections or spoil ballots as a form of protest against Beijing’s overhaul of the city’s electoral system.

They raised concerns about the pitfalls of creating an incitement offence for acts that would otherwise be legal in themselves, as the government on Wednesday tabled an umbrella bill in the Legislative Council consolidating a host of legal amendments and subsidiary legislation to implement Beijing’s shake-up of the system.

The proposed ban also raised questions on the legality of hypothetical situations, and prompted online users to float ideas on how to convey their political messages in coming elections without falling foul of the new law.

Under the amendments to the Elections (Corrupt and Illegal Conduct) Ordinance, inciting others “not to vote, or to cast invalid votes” through public activities during an election period will be considered illegal, and punishable by up to three years in prison.

The bill stipulates “activity in public” as: any form of communication to the public, including speaking or other recorded material; any conduct observable by the public, including actions and gestures; and the distribution or dissemination of any matter to the public.

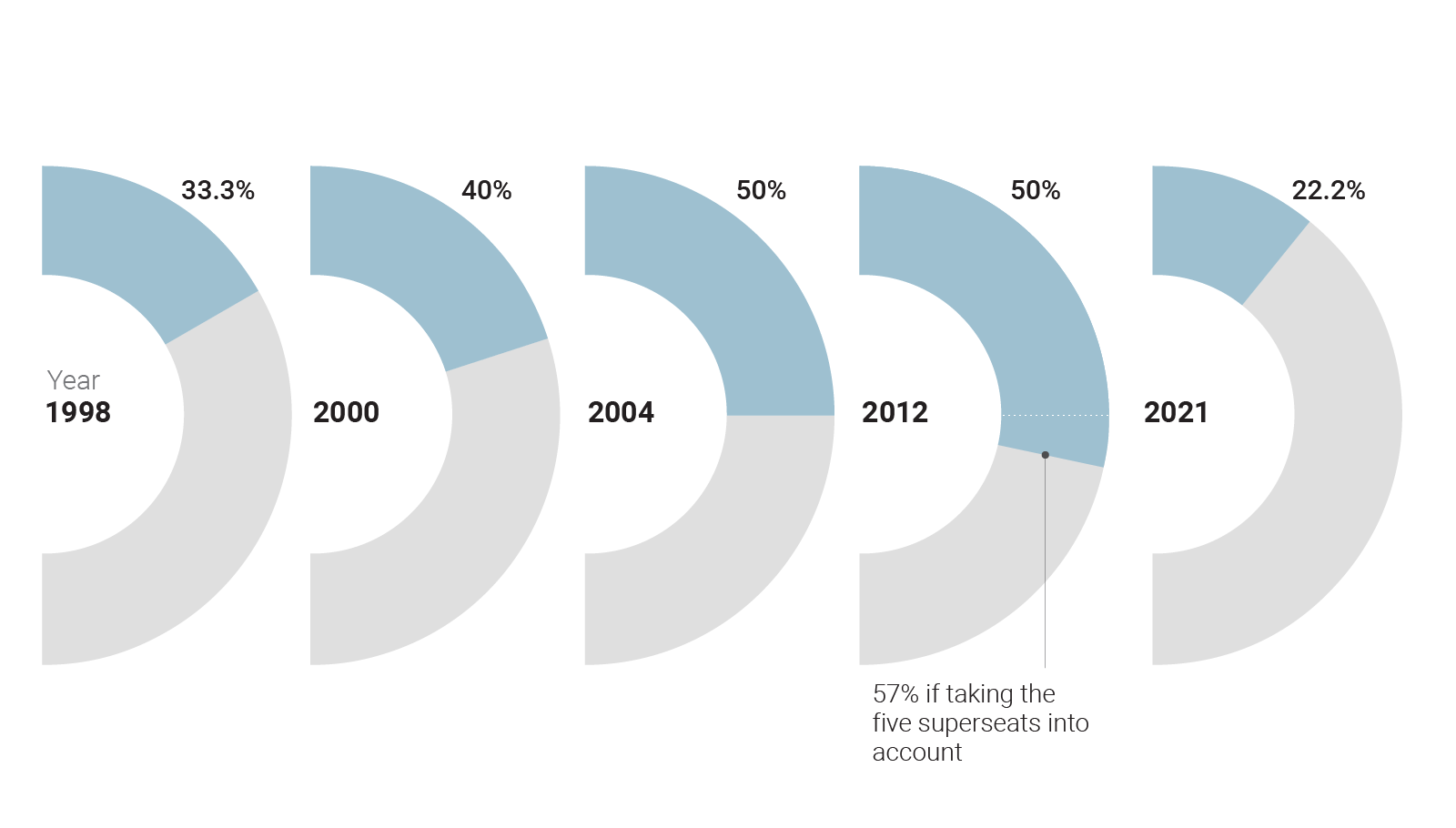

The evolution

Percentage of directly-elected seats

Simon Young Ngai-man, associate law dean at the University of Hong Kong, told the Post the proposed offence was “problematic” as it did not specify the required mental element.

He said the common law offence of incitement criminalised the incitement of acts which constituted a criminal offence, not acts which were perfectly lawful in themselves.

“It is rather unusual to create an incitement offence in relation to acts that are perfectly legal in themselves,” said Young, who was among legal professionals who demanded the government justify the amendments.

The veteran lawyer also pointed to “real constitutional problems” with the proposed offence, saying it was a disproportionate means to achieving the government’s aim of preventing anyone from creating undue pressure on voters.

Professor Simon Young.

Professor Simon Young.

He said the actual impact was irrelevant in legislation on incitement, which criminalised conduct considered capable of persuading a person to act in a certain way, regardless of whether it actually influenced that person to act or even consider acting.

A day after the government unveiled a host of bills to amend local laws in line with the sweeping electoral changes, online users posted ideas on how to advocate blank votes or boycotts without breaching the law.

One created a poster that called for “supporting Pat Piu”, a local actor whose name in Cantonese sounds like “blank votes”. Some proposed to don plain white, display white paper at polling stations, or raise white curtains at home during elections.

Online users attempted to highlight the vagueness of the proposal by raising hypothetical situations.

Some asked: “Can I call for boycotts on my own Facebook page or WhatsApp groups?” Others raised the question of whether it was illegal to retweet calls for blank votes, and another person commented: “Can I ask Hongkongers to join efforts in achieving a new low in voter turnout?”

Lawyer Anson Wong Yu-yat, who practises both criminal and public law, said it would be hard to determine whether such a call on private social media accounts would amount to the accused communicating with the public.

“If the post was made accessible to all, it may be obvious,” he said. But he added it would be more problematic if the post was only for a few Facebook friends and the court would have to draw a line on a case-by-case basis.

Wong said he could not fathom why it would be unlawful to incite others on a completely legal act. He believed that a defendant would not be found guilty if the court was satisfied the alleged message could still offer the slightest possibility of a lawful alternative.

A legal source, speaking on condition on anonymity, cited views of the European Court of Human Rights which accepted that the use of ballot papers for any other purpose than casting a vote did not necessarily impinge on the fair conduct of elections or otherwise violate the rights of others.

“The particular importance of free speech to elections requires that in the period preceding an election, opinions and information of all kinds be permitted to circulate freely,” the source said. “It is axiomatic that, under the common law, the same approach must be obtained.”

Baggio Leung.

Baggio Leung.

Presenting the bill in Legco, Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Erick Tsang Kwok-wai said the electoral overhaul was a necessary step following the 2019 social unrest and last year’s implementation of the national security law to plug loopholes that allowed anti-China forces to obstruct governance.

“There are still anti-China perpetrators who made use of their capacity as councillors to overthrow the governing power of our nation,” he said. “[Beijing’s decision] is perfectly legitimate and reasonable … This provides a sound foundation to ensure Hong Kong’s system is governed by patriots.”

Ousted pro-independence lawmaker Sixtus Baggio Leung Chung-hang, who was reported to have left the city for the United States, on Wednesday called for spoiled votes in the coming Legco elections set for December 19, as a way of protesting against the perceived tightening of Beijing’s grip over the city.

“It’s difficult to organise a protest now before new strategies emerge … Here comes a chance to show our comrades: ‘We are still there’. Why don’t we do it when it’s still allowed?” he said in a Facebook post.