Hong Kong News

Jews who escaped the Nazis through loophole, the Chinese envoy who helped them

Until this week, Andrea Fessler had never heard of Ho Feng-shan, a Chinese diplomat who helped her father and grandparents survive World War II.

As a consul general to Vienna, he defied his government and issued thousands of visas that enabled persecuted Jews to escape from Austria to Shanghai in 1938 and 1939.

Among those who fled their hometown of Vienna in 1938 for Shanghai were Fessler’s grandparents, Alexander and Klara, and their three-year-old son Fred, her father.

Fessler was told her grandfather, a hairdresser, decided to leave after he was beaten up on the street for being Jewish.

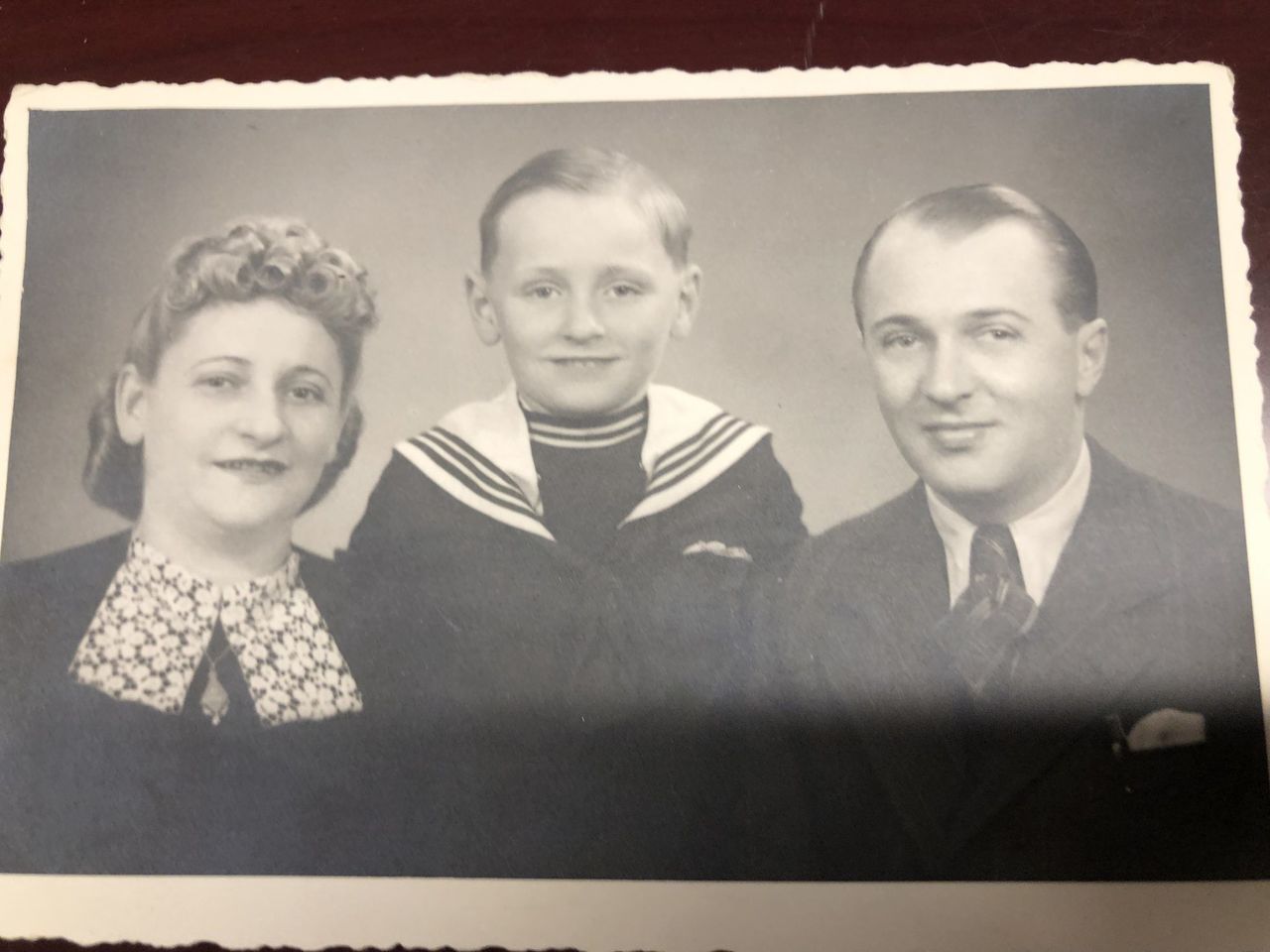

Alexander and Klara Fessler and their son Fred were among those that fled Austria for Shanghai in 1938.

Alexander and Klara Fessler and their son Fred were among those that fled Austria for Shanghai in 1938.

It was in 1938, when Austria was annexed by Germany, that the Nazis unleashed a reign of terror against the Jews. Over two days that November, more than 200 synagogues were destroyed in Austria and Germany, 7,500 Jewish shops looted and 30,000 Jews were sent to concentration camps.

That was Kristallnacht, “the night of broken glass”.

That year, Ho Feng-shan began issuing visas to Jews as “proof of emigration” to leave Austria for the port city of Shanghai, and word spread that it was a potential haven for those desperate to escape.

Fessler’s grandfather Alexander was among those who heard that Shanghai offered hope and went there. The family returned to Vienna in 1949, before emigrating to Canada.

Fessler, 53, a Canadian, moved to Hong Kong in 2004 with her husband and two daughters. Speaking to the Post from her office in Causeway Bay, she said she was amazed to learn of Ho Feng-shan’s role in saving the lives of so many Jews, including her family members.

Andrea Fessler recently discovered that Chinese diplomat Ho Feng-shan helped her family survive World War II.

Andrea Fessler recently discovered that Chinese diplomat Ho Feng-shan helped her family survive World War II.

Tearing up, she said: “I feel very emotional to discover that it was because of one consul general. He was able to save all of these people.”

From December 8 to Christmas Day, the city will mark the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Hong Kong, when the Japanese overwhelmed British and allied forces. The Japanese occupied Hong Kong for the next three years and eight months.

A daughter’s detective work

This year is also the 120th anniversary of the birth of Ho Feng-shan, whose story only became known after he died in 1997 and his daughter, Ho Manli, uncovered details about what he did in Vienna.

She remembered that when she was a child, her father would tell a story about his time as consul general in Vienna for two years from April 1938.

After witnessing the attacks on Jews during Kristallnacht, the 37-year-old went to visit his Jewish friends, the Rosenbergs, and issued them visas to go to Shanghai.

However, on the morning of their departure, Mrs Rosenberg told him that her husband had been arrested. Ho Feng-shan went to their home and was in the living room when two Gestapo officers in trench coats turned up.

When he informed them that he was waiting for his friend to return, one of the officers pulled a gun on him angrily, demanding to know who he was.

The officers left after Mrs Rosenberg told them that he was the Chinese consul general. Her husband was released later that day and the couple left the country.

Ho Manli, now 70, spoke to the Post from her home in San Francisco and said she included a brief account of that story in her father’s obituary.

The curator of an exhibition about diplomats who saved Jews during the war then contacted her. They met, and when she confessed that she did not know more about her father’s story, he said: “You’re a newspaper reporter, don’t you want to know?”

That got her started, piecing together what had happened six decades earlier.

Through the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Ho Manli learned of Eric Goldstabb who went to more than 50 consulates in Vienna before the Chinese consulate gave him 20 visas to take his family to Shanghai.

A picture of late Chinese diplomat Ho Feng-shan is seen at ‘On the Wings

of the Phoenix: Dr Feng-shan Ho and the Rescue of Austrian Jews’ in the

US.

A picture of late Chinese diplomat Ho Feng-shan is seen at ‘On the Wings

of the Phoenix: Dr Feng-shan Ho and the Rescue of Austrian Jews’ in the

US.

When she was shown one of their passports, the visa serial number and date – 1, 193 issued on July 20, 1938 – revealed that her father had done much more than he had let on.

“That was when I realised that my father had not just saved his friends, the Rosenbergs, like in the story he told me,” she said.

He may have started out helping his friends, but ended up saving thousands.

In his memoir he wrote: “Seeing the tragic plight of the Jews, it was only natural to feel deep compassion and, from the standpoint of humanity, to be impelled to help them.”

Goldstabb was among the survivors who wrote testimonials to Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre, which launched an investigation into what Ho Feng-shan did in Vienna. That led to Israel honouring him posthumously in 2000 with the title “Righteous Among the Nations,” one of its highest civil honours.

But why did her father send fleeing Jews to Shanghai?

Ho Manli said that after China had been invaded by Japan in 1937, any document or entry visa issued by a Chinese diplomat would not have been recognised. But her father found a loophole in the administrative chaos of the time, whereby Shanghai remained an open port without proper immigration control.

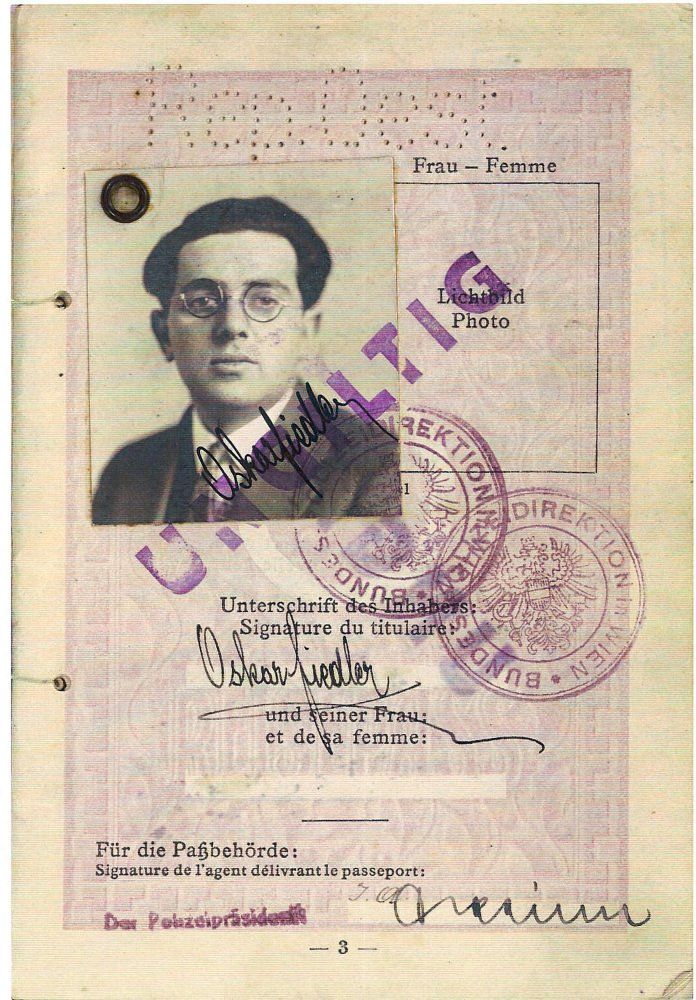

Oskar Fiedler (pictured) was one of the many Austrian Jews to be given a visa by Ho Feng-shan.

Oskar Fiedler (pictured) was one of the many Austrian Jews to be given a visa by Ho Feng-shan.

The biggest effect of her father issuing visas against his superiors’ orders was that word spread among Jews not only in Austria but also in Germany and Czechoslovakia, that Shanghai was a place they could escape to.

In total, 18,000 European Jews ended up in Shanghai, with around 4,000 to 5,000 from Austria.

Ho Feng-shan knew that many of the Jews had no intention of settling in Shanghai, but the visa enabled them to get out of Europe. He wrote in his memoir: “The visas were to Shanghai in name only. In reality, they could use them to facilitate their passage to other preferred destinations.”

As a result, thousands of Jewish families ended up in Portugal, Cuba, the United States, Palestine, the Philippines and Australia.

“My father came up with this brilliant strategy,” Ho Manli said.

But her research also uncovered that he suffered for what he did.

Ho Feng-shan issued visas to Austrian Jews to help them escape the Nazis

Ho Feng-shan issued visas to Austrian Jews to help them escape the Nazis

Upon learning that he was issuing visas to Jews, the Chinese ambassador to Berlin, Chen Jin, called Ho Feng-shan and ordered him to stop. When he refused, Chen sent a subordinate to Vienna to investigate whether he was being bribed by the Jews he helped, but the officer could find no evidence.

In early 1939, the Nazis confiscated the consulate building. Ho asked for funds to relocate and when his superiors refused, he rented smaller premises at his own expense and reopened the consulate.

Two years ago, Ho Manli obtained records from the national archives of Taiwan which showed that a report from the Chinese embassy in Berlin said her father was not fit to be consul general in Vienna. He was replaced and sent to Berlin in 1940.

“In Chinese bureaucracy, you do not disobey your superior. You do your best to toddy up to your superior in every way. So my father, in a lot of ways, was a terrible bureaucrat,” she said with a laugh. “He did not play by the rules.”

Through the 1940s, her father was posted to the United States, and rejoined the foreign ministry in 1943, taking up the post of ambassador to Egypt and seven Middle Eastern countries.

When the Chinese civil war ended in a communist victory in 1949, he chose to stick with the Nationalists, led by Chiang Kai-shek, who fled to Taiwan. He went on to be posted to Mexico, Bolivia and Colombia.

However, at the end of his career, he was impeached and denied a pension over an accusation that he could not account for US$200 (HK$1,559) of embassy expenses, according to Ho Manli, who believed it was the result of a political vendetta as he might have offended one of Chiang’s sons, Ching-kuo.

Her father retired to California in 1973 and died there on September 28, 1997, aged 96.

Ho Manli said that part of the reason she embarked on the journey to find out her father’s story was to clear his name.

In 2015, then Taiwanese president Ma Ying-jeou honoured her father posthumously with a commendation while marking the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II in Asia. However, he was never formally exonerated.

But Ho Manli said she took comfort in the evidence she unearthed showing that at the worst of times, her father did the humanitarian thing.

Several Jewish people whose relatives fled Europe with visas signed by her father have met her over the years to express their gratitude.

Hedy Durlester hugs Manli Ho, whose father helped her mother and father to escape Austria in 1938.

Hedy Durlester hugs Manli Ho, whose father helped her mother and father to escape Austria in 1938.

Daniel Wiehs, 79, who lives in Israel, said his mother Roszi obtained a visa signed by Ho Feng-shan, and that helped her get her fiancé Hugo out of a concentration camp before they fled for Shanghai. The couple married and their son was born in China.

“If we don’t remember, then things like that might happen again. Hopefully, when we hear about people like [Ho Feng-shan], it may help prevent such [an] atrocity in future,” Wiehs said.

Amir Lati, the Israeli consul general in Hong Kong, agreed and said Ho Feng-shan acted bravely at a time when few people would have done what he did.

“He saved thousands of lives, which means tens of thousands of people are alive today because of his deeds,” he said.

Canadian Harry Fiedler, 82, whose parents also escaped from Vienna with those prized visas, recalled feeling emotional when he met Ho Manli at the United Nations headquarters in New York in 2000, at an event honouring diplomats who provided visas to Jews during World War II.

He said of her father: “He was a hero for the Jews. He saved many, many lives. I wish I would have had the chance to meet him.”

Ho Manli said that as the last surviving member of her immediate family, meeting the Jewish survivors was special to her.

“When I see these people who were able to benefit from my father’s help, I jokingly call them my mishpuche, which means family in Yiddish. It is like he lives on through them,” she said.