Hong Kong News

Is Hong Kong’s judicial independence hanging in the balance?

Hong Kong’s judicial independence is teetering on a knife’s edge, Britain’s foreign minister has suggested in her latest report on the city, drawing swift rebukes from Beijing and the local government.

In her report covering the first six months of the year, released on Tuesday, Liz Truss expressed reservations for the first time over a legal system that London had previously called reputable, but said she believed British judges continued to have a constructive role to play by sitting in Hong Kong’s courts through a long-established tradition aimed at boosting international confidence.

“Our assessment of Hong Kong’s judicial independence is increasingly finely balanced, but for now I believe that British judges can continue to play a positive role in supporting this judicial independence,” Truss wrote.

Britain’s Foreign Secretary Liz Truss.

Britain’s Foreign Secretary Liz Truss.

That assessment, however, drew the ire of China’s local foreign ministry office, which accused the United Kingdom of harbouring ulterior motives in releasing the report just ahead of Sunday’s Legislative Council poll.

“The intention of the British side putting together the so-called report before the Hong Kong Legco election is to interfere in Hong Kong affairs and disrupt the election order of [Hong Kong],” the office said in a statement.

Beijing “strongly disapproved, firmly rejected and condemned” the report, a spokesman said, adding it “smeared the rule of law and development in Hong Kong, slandered the successful practice of ‘one country, two systems’, vilified the national security law … and seriously trampled on the principles of international law and the basic norms governing international relations including ‘non-interference in others’ internal affairs’.”

A spokesman for the Hong Kong government, meanwhile, said it “strongly opposed the unfounded allegations” in the report, and also called on the UK to “stop interfering in the internal affairs of China through Hong Kong affairs”.

Britain’s secretary of state for foreign, commonwealth and development affairs has been charged with issuing the reports every six months since 1997, when the city returned to Chinese rule, to monitor Beijing’s implementation of the Sino-British Joint Declaration, a 1984 agreement between the two countries on the future of the city.

Jimmy Lai is facing national security law offences.

Jimmy Lai is facing national security law offences.

Previous reports have stayed away from heavy criticism of Hong Kong’s judiciary, even as the city’s courts oversaw a flurry of politically charged cases linked to the 2019 anti-government protests.

In an earlier report chronicling events between July and December 2019, then British foreign secretary Dominic Raab said the city’s courts were expected to deal with cases concerning pro-democracy and opposition figures in “a fair and transparent manner for which Hong Kong’s judiciary has a renowned reputation”.

But the new document, which covers developments from January to June this year, cited the Court of Final Appeal’s ruling to refuse bail for media tycoon Jimmy Lai Chee-ying – the founder of the now-folded Apple Daily paper who is facing national security law charges.

It also noted that Tong Ying-kit, the first person charged in Hong Kong under the national security law for driving his motorcycle into a group of police officers last year while flying a flag calling for the city’s “liberation”, stood trial without a jury.

The city’s justice secretary, Teresa Cheng Yeuk-wah, had cited concerns for the personal safety of jurors and their families.

Tong was eventually convicted and jailed for nine years.

Tong Ying-kit, seen here, was the first person charged in Hong Kong under the national security law.

Tong Ying-kit, seen here, was the first person charged in Hong Kong under the national security law.

Tuesday’s report reiterated London’s opposition to the national security law imposed by Beijing in June last year.

“We are now seeing the effects of a law with loosely defined provisions, backed up by the threat of potentially long jail sentences and transfer of cases to mainland China for prosecution and sentencing,” it stated.

“Confidence in the rule of law will be undermined if there are further politicised prosecution decisions,” the report added.

Also included was a remark made in June by Zheng Yanxiong, director of Beijing’s Office for Safeguarding National Security in Hong Kong, who argued that the city could lose its independent judicial power, originating from Beijing, if it failed to uphold the country’s interests.

Attacks by Beijing’s liaison office in Hong Kong directed at Paul Harris, a British-born barrister who is currently head of the local Bar Association, were also documented.

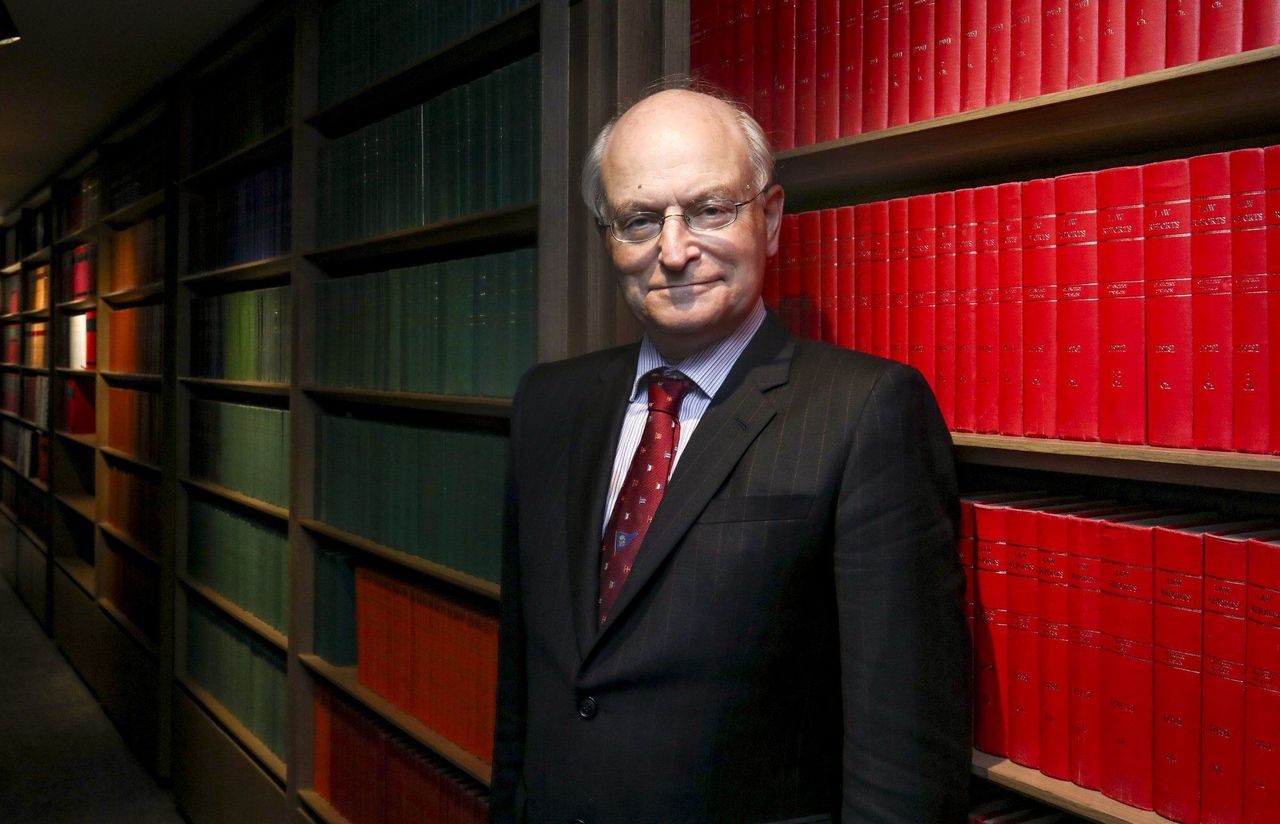

Bar Association chief Paul Harris.

Bar Association chief Paul Harris.

While the UK government would wish to see the tradition of British judges sitting in Hong Kong courts continue, the report said, it would not impose any such obligation on them.

“The UK judiciary is independent of the government and it is for the judges themselves to make their own decisions regarding their continued service in Hong Kong. The UK Supreme Court continues to assess the situation in Hong Kong, in discussion with the UK government,” it said.

UK-based scholar Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute at the University of London, noted the careful choice of words.

“For the foreign secretary to describe the continuation of judicial independence as ‘increasingly finely balanced’ is to acknowledge the great discomfort she has over the current state of affairs, while she is trying to do everything she can to slow down the erosion of an independent judiciary in Hong Kong,” he said.

Thomas Kellogg, executive director of the Georgetown Centre for Asian Law, noted the concerns of the UK government, but said it was also making a “tough call” letting the judges remain in the city.

“If they leave, they would no doubt have the opportunity to signal to the international community the threats that the Hong Kong court system faces, which would have some value. But then the moment would pass, and the courts would be left without one key source of comparative experience and expertise,” he said.

Former Hong Kong director of public prosecutions Grenville Cross called the report “clearly partisan”, saying it reflected “animosity which the UK Foreign Office has displayed towards Hong Kong in recent times”.

He said the report had omitted remarks made by senior British judges who took no issue with the city’s rule of law. For example, British Supreme Court president Robert Reed, when reaffirming his decision in August to continue serving in Hong Kong’s courts, said legal decisions coming out of the city remained “consistent with the rule of law”.

“Although the foreign secretary, Liz Truss, is still new to her job, she will hopefully take a closer interest in the next six-monthly report, and try to ensure that it has, at least, a veneer of objective reporting,” Cross said.

The report also raised concern over artistic freedom for the first time in recent years, pointing to new guidelines issued by the Hong Kong government in June to censor films considered national security threats.

Other areas the report touched on included press, internet and academic freedom.