Hong Kong News

How Hong Kong can get its water conservation ducks in a row

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was adopted by all United Nations member states in 2015. It is a plan of action for both developing and developed nations to achieve 17 sustainable development goals, which cover a range of environmental and social issues, by 2030.

Today is World Water Day, so let’s take a closer look at the sixth goal, which aims to ensure access to safe drinking water and sanitation for all.

Currently, there are more than 733 million people living in places with high or critical levels of water stress. Climate change, pollution and development have created tremendous threats to water security in many countries, with developing nations the most vulnerable.

The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022 revealed that at current rates, 1.6 billion people will lack safely managed drinking water by 2030, and 2.8 billion people will lack safely managed sanitation. Meeting the targets by 2030 will require a fourfold increase in the pace of progress.

Water and oil are both liquid resources essential for human survival and economic development. No renewable energy can fully replace oil as yet. So, humanity has to use these finite resources sustainably by conserving them and minimising wastage.

Fortunately, some water-stressed nations have applied sound strategies and technologies to address water scarcity successfully. Hong Kong needs to learn from them to develop sustainable strategies tailored to the city’s situation.

Confronted with an arid climate, Israel has used desalination technology since 2005 to turn seawater into potable water. But this is an energy-intensive technology, which will result in heavy carbon emissions if zero-carbon renewables are not used to power the desalinators.

Israel is also considered the global leader in water recycling with around 90 per cent of its waste water treated for reuse in drip irrigation, a water-efficient technology developed for agriculture enabling the cultivation of many types of fruit, including citrus fruit, avocados and mangoes, for local consumption and export.

Then there’s Singapore, which, with limited space for reservoirs and keen to reduce reliance on importing fresh water from neighbouring Malaysia, has effectively treated its sewage for reuse and even for drinking. Currently, the reused water produced from its advanced system amounts to 40 per cent of Singapore’s total water demand and authorities plan to raise this to 55 per cent by 2060.

Most of the reused water has been put to industrial and commercial uses, such as the water-intensive microchip manufacturing industry and cooling for air conditioning systems in commercial buildings. However, the authorities did not stay in their comfort zone, and by launching promotional campaigns, they eventually convinced the public to accept drinking water that contains reused water which meets safe potable water standards.

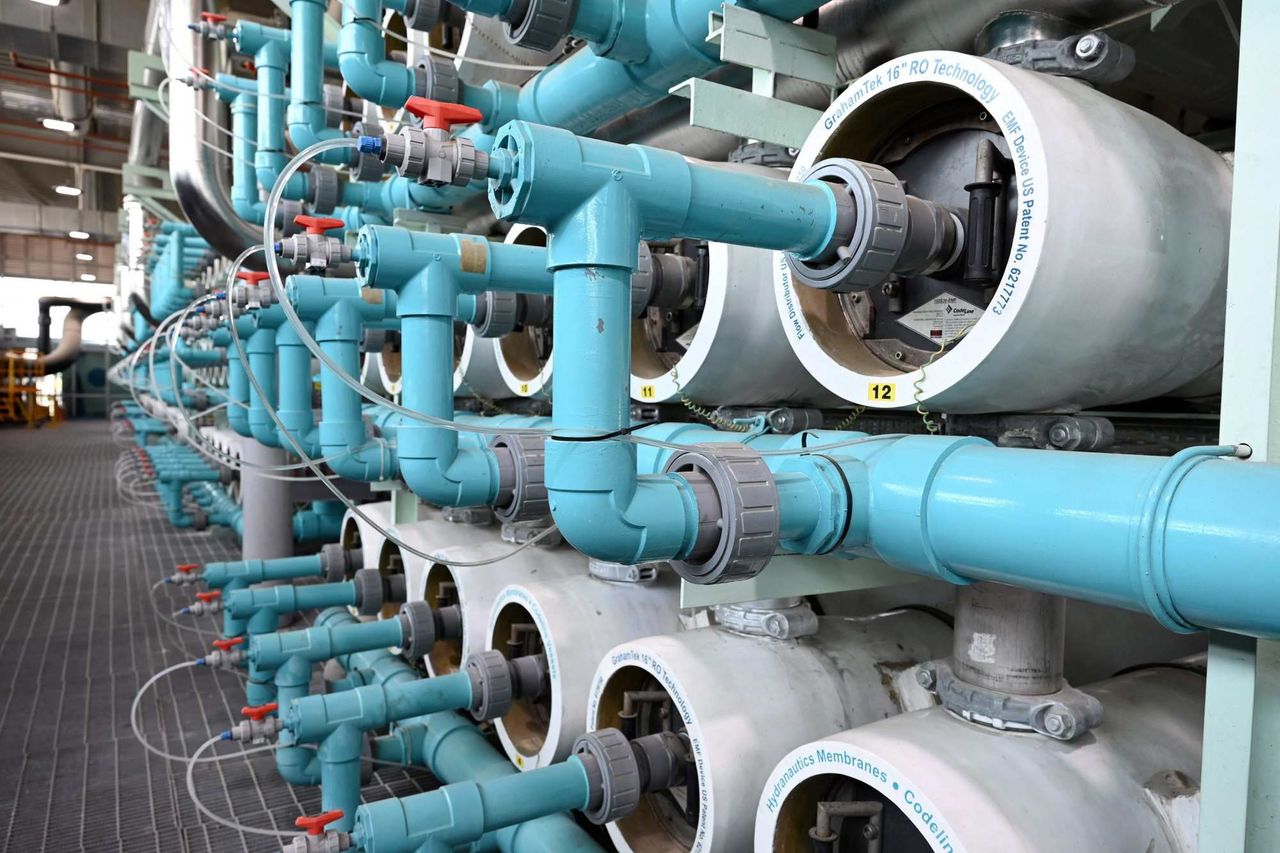

The reverse osmosis treatment on used water equipment at the Bedok

NEWater plant, where sewage is transformed into water fit for human

consumption, in Singapore in July 2021.

The reverse osmosis treatment on used water equipment at the Bedok

NEWater plant, where sewage is transformed into water fit for human

consumption, in Singapore in July 2021.

To tackle water scarcity effectively, we should be paying attention to reducing consumption at source as well as cutting wastage by limiting leakage throughout the water distribution network, both in public and private areas.

In Hong Kong, the Water Supplies Department (WSD) aims to reduce leakage rate from the public mains from 15 per cent in 2019 to less than 10 per cent by 2030 by implementing the Water Intelligent Network, which uses sensors and telemetry.

The city’s total water consumption has kept rising. It broke a new high last year when 1,066 million cubic metres (mcm) of fresh water were consumed. Therefore, the earlier we can meet or exceed the 10 per cent goal, the better.

Based on the city’s 2019 water consumption of 996 mcm, the 15 per cent leakage in 2019 is equivalent to wasting 149.4 mcm of fresh water, or the volume of 59, 760 Olympic-size pools. Clearly this is an avoidable wastage.

People at Kowloon Park swimming pool on August 7, 2022.

People at Kowloon Park swimming pool on August 7, 2022.

There are practical ways to conserve water, such as placing floating solar panels on reservoirs to reduce the water evaporation rate while producing zero-carbon energy to alleviate climate change.

Why don’t we change to using reused water to cool air conditioning systems in our office buildings, data centres and tertiary institutions? By doing so, we can save a lot of precious fresh water until Hongkongers are willing to accept drinking water that has been recycled from sewage like Singaporeans do.

We can look for detailed information about water-efficient equipment and water saving tips on the WSD’s homepage. We should also be mindful of the water footprint of food and commodities. The water footprint calculator developed by the University of Hong Kong can give us some guidance.

I recall an old Chinese proverb advising people to prepare for rainy days. Today, it is more appropriate to advise people to prepare for droughts.