Hong Kong News

Hongkongers need more than flashy ‘Strive and Rise’ scheme to beat poverty

The government-led Strive and Rise mentorship programme, benefiting 2,800 students living in subdivided flats, began this past weekend. Leading the programme is Chief Secretary Eric Chan Kwok-ki, who has received support from more than 100 enterprises and organisations, with HK$140 million (US$17.8 million) raised in sponsorship funding.

The 2,800 underprivileged students will each be assigned a mentor and receive a total of HK$10,000 should they complete the programme. It includes some 800 group activity sessions, mandatory courses in communication skills, financial and life planning, and optional interest classes that include social etiquette, language learning and sports conducted by celebrities and star athletes.

The government has brought 20 “strategic partners” on board after they provided key support in sponsorship or nominating mentors. They include Henderson Land, HSBC, Bank of China (Hong Kong), China Resources Group, Sun Hung Kai Properties and New World Development.

If anyone thinks this star-studded bureaucratic monstrosity will inspire hope in the city’s neediest and lead our fight in eradicating intergenerational poverty, they are truly mistaken. It’s an exercise of counting a show of hands to see who will support the government, and how much they will pledge. It’s also a way for those taking part to feel they are doing good, which is nice – for them.

But for students and their families to feel they have a better tomorrow to look forward to, there needs to be real political will and leadership from the government. We must reject the key performance indicator set for Strive and Rise, which is to have “no less than 70 per cent of students who complete the one‐year Strive and Rise Programme to achieve improvement in terms of personal development and positive thinking”.

It is patronising to claim the poor are “negative”. Of course they are, and it is not only them, either. Look at how the Hong Kong stock market has plummeted, back to 1997 levels last week. That creates the kind of pessimism the government needs to address.

A friend who has built a career serving the needy and working in community building told me subdivided homes are now called “poverty showrooms” in certain circles. Even worse is that there are many more families that are vulnerable.

Often going unnoticed are the working poor who are “lucky” enough not to be stuck in a subdivided flat but still struggle to make ends meet. There is not much else they can afford, including time off, and their children cannot take part in activities outside school. Life is harsh, miserable and full of uncertainties.

It doesn’t help that the Covid-19 pandemic has made life tougher for the underprivileged. According to the Hong Kong Poverty Report, released by Oxfam earlier this month, poverty has grown worse during the pandemic.

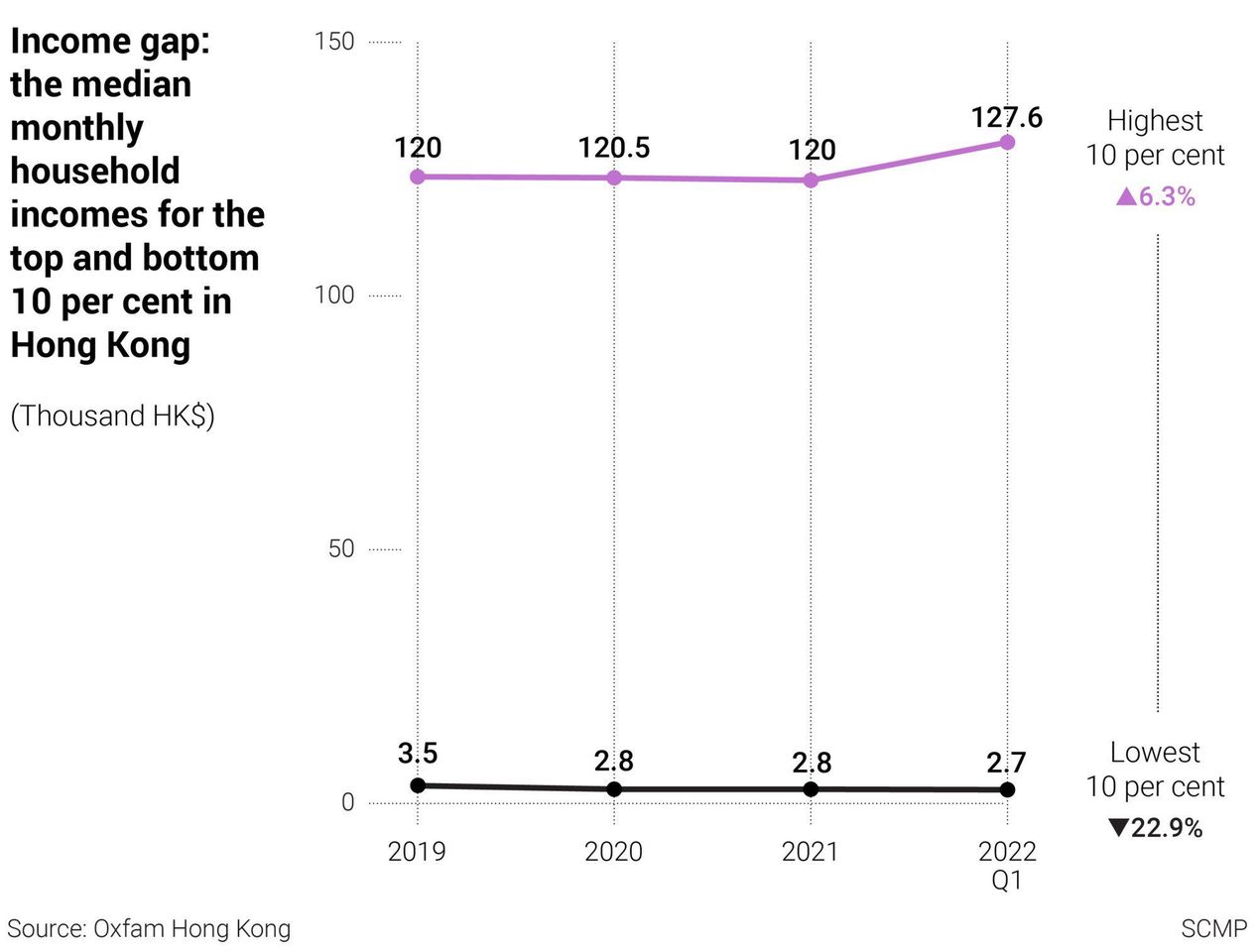

The wealth gap widened and the city’s richest people earn over 47 times more than the poorest. According to Oxfam’s analysis, the unemployment rate among poor people reached 26.1 per cent in the first quarter of this year. We are only just opening up, but we must be aware of the repercussions policy decisions have on lives and families.

Decreased income, job losses, work stoppages and inflation during the pandemic are especially damaging to the most vulnerable. We should be looking at creating economic growth and putting forward policies that ensure growth reaches those who need it and increases access to opportunities and social mobility.

In short, we have to recognise there are structural odds stacked against the poor. Their inability to leave the vicious cycle of poverty isn’t because of their lack of “positive thinking”. Positive thinking is important in overcoming adversity, but poverty is a much bigger issue than that.

The cardinal mistake is assuming a big programme like “Strive and Rise” will lift people out of poverty without any commitment to making broader changes. Mentors are not going to give poor children a proper roof over their heads and their parents job security, let alone jobs that pay them a living wage.

Poverty alleviation requires changes in institutions, better governance and the right public policies while taking into account all the challenges the city faces.