Hong Kong News

Hong Kong wants Beijing to interpret national security law. Here’s why it matters

Hong Kong’s top court on Monday ruled a prominent British barrister could defend media tycoon Jimmy Lai Chee-ying, immediately triggering yet another political storm as the city’s leader asked Beijing to intervene.

Hours after the Court of Final Appeal’s ruling, Chief Executive John Lee Ka-chiu said he had asked the National People’s Congress (NPC) Standing Committee for an interpretation of the national security law to decide whether lawyers who did not practise generally in Hong Kong should be allowed to argue these cases.

Here is what you need to know about the possible interpretation of the national security law, which Beijing imposed on Hong Kong in 2020, and what implications it has for the city’s legal system.

Hong Kong Chief Executive John Lee.

Hong Kong Chief Executive John Lee. 1. What is the dispute about?

The legal tussle was triggered by the Department of Justice after Lai, the 74-year-old founder of the now-defunct Apple Daily who faced charges of collusion with foreign forces, hired British King’s Counsel Timothy Owen to defend him in a trial originally expected to start on Thursday.

The government took the case to the Court of Final Appeal after losing its bid to block Owen from the trial in the lower courts, arguing the admission of overseas counsel in cases involving national security was “incompatible with the overall objective and design” of the legislation.

City leader Lee decided to ask the NPC Standing Committee to interpret the national security law after the top court upheld its decision to allow Owen to defend Lai. His move was backed by Beijing’s officials overseeing the city’s affairs, who said the court decision had violated “the legislative spirit and legal logic” of the national security law.

On Tuesday, Secretary for Justice Paul Lam Ting-kwok requested the court adjourn Lai’s case as the city awaited Beijing’s ruling.

Tycoon Jimmy Lai hired British King’s Counsel Timothy Owen to defend him.

Tycoon Jimmy Lai hired British King’s Counsel Timothy Owen to defend him. 2. How has Beijing interpreted laws before?

The NPC Standing Committee has interpreted the city’s mini-constitution, the Basic Law, on five occasions in the 25 years since the city’s handover to Chinese rule.

The execution of the standing committee’s power to issue interpretation has proved controversial in the past.

The most recent interpretation came in 2016, after newly elected lawmakers Sixtus Baggio Leung Chung-hang and Yau Wai-ching used their oath-taking in the Legislative Council to criticise China. The apex body declared that new lawmakers who failed to take their oath sincerely or properly could be disqualified immediately.

But Lee’s request, if approved, would be the first time the standing committee has interpreted the national security law, and it remained unknown which clause would be explained.

Constitutional law expert Professor Albert Chen Hung-yee, of the University of Hong Kong, said the interpretation of the security legislation – a national law – was not required to go through the Basic Law Committee, which is composed of both mainland Chinese and local members.

3. What are the arguments on each side?

In its repeated appeal attempts, the government contended that overseas counsel could not furnish judges with new perspectives on the national security law, as they lacked a full understanding of the city’s unique sociopolitical and constitutional context.

Admitting overseas lawyers in cases concerning Beijing’s interest would “generally tend to defeat the aim” of the national security law, which was enacted to tackle interference in Hong Kong’s affairs by foreign or external forces, it contended.

The government also insisted there would be no “meaningful or effective enforcement” of overseas council’s confidentiality obligations under Article 63 of the security law over with respect to state secrets and other confidential information which the counsel might come to know during the trial.

But the courts found the contentions not “reasonably argued”, saying a balance between safeguarding national security and protecting freedom of expression should be struck in the landmark case and that the admission of a high-calibre barrister would in fact aid in the development of the city’s jurisprudence.

The bench also ruled it was unnecessary to be concerned with a hypothetical situation of possible disclosure of state secrets by some overseas counsel, adding foreign lawyers would also be subject to the code of conduct.

In announcing his decision to take the case to Beijing, Chief Executive Lee argued there was currently “no effective means” to ensure that overseas counsel would not have a conflict of interest because of their nationality, that they had not been coerced or controlled by foreign agencies and that they would not divulge information such as state secrets.

4. What kind of lawyers could be affected?

Lee stressed that the government only sought to bar lawyers who did not generally practise in the city from arguing national security cases, but not those legal practitioners registered in Hong Kong who held foreign passports.

He brushed aside concerns his move would damage the city’s legal reputation, saying defendants involved in national security crimes were still free to choose lawyers who were fully qualified in Hong Kong.

But legal experts questioned the grounds of drawing a line in the sand this way.

Professor Johannes Chan Man-mun, former law dean of the University of Hong Kong, said he did not see any legitimate difference between an overseas lawyer and a local one with a foreign passport.

“How about senior civil servants, senior members of the disciplinary forces, other professionals such as accountants and so on who may have access to sensitive confidential information or state secrets?” he said.

“Are there to be requirements that holders of foreign nationality should not be allowed to hold these positions then? If judges holding foreign nationality are not restricted from trying national security cases, why should lawyers of foreign nationality be restricted from representing their client in national security cases?”

Senior Counsel Philip Dykes, former chairman of the Bar Association, said the government’s position was confusing, arguing the crux of the issue was whether the advocate could be trusted and was not an unacceptable security risk.

5. Could foreign judges be banned from trying national security cases next?

Hong Kong is one of the few former British colonies that has retained a mechanism of inviting judges from other common law jurisdictions to sit on the Court of Final Appeal, an arrangement enshrined in the Basic Law.

On Monday, Lee said the government had no plans to ban foreign judges from trying national security cases.

There was an established mechanism in place to recommend – and subsequently appoint – judges, who are also required to go through an integrity check before taking an oath, he said. He also pointed to the requirement under the Beijing-imposed legislation that all national security cases should be heard by a pool of designated judges hand-picked by the city’s leader.

“We have a strict mechanism regarding the appointment of judges, which is totally different from that of the overseas solicitors and barristers,” he said.

6. What are the controversies surrounding the request?

Ahead of the Court of Final Appeal’s ruling, several veteran pro-Beijing politicians had openly opposed Owen’s involvement in Lai’s case.

Former chief executive Leung Chun-ying said it was “ridiculous” for someone accused of colluding with foreign forces to be represented by a lawyer from abroad.

Tam Yiu-chung, Hong Kong’s sole delegate to the NPC Standing Committee.

Tam Yiu-chung, Hong Kong’s sole delegate to the NPC Standing Committee.

Tam Yiu-chung, Hong Kong’s sole delegate to the NPC Standing Committee, said a few days before the court’s decision that Beijing would have to step in to interpret the national security law “to correct the misunderstanding” if the top court upheld its decision to allow Owen to defend Lai.

Legal scholar Chan said the extensive discussion was “disturbing”, as such advocacy for a particular view would only undermine the rule of law and public perception of judicial independence.

He added the government’s announcement to seek an interpretation from Beijing to reverse the top court’s judgment within hours of the ruling would inevitably leave a legitimate doubt in the minds of the public and the international community about the utility of the judicial proceedings.

“The government is determined to have its way, and judicial decisions from the highest court could be brushed aside,” Chan said. “No matter how hard the government tries to tell the international community about the rule of law in Hong Kong, the interpretation would send a completely contradictory message.”

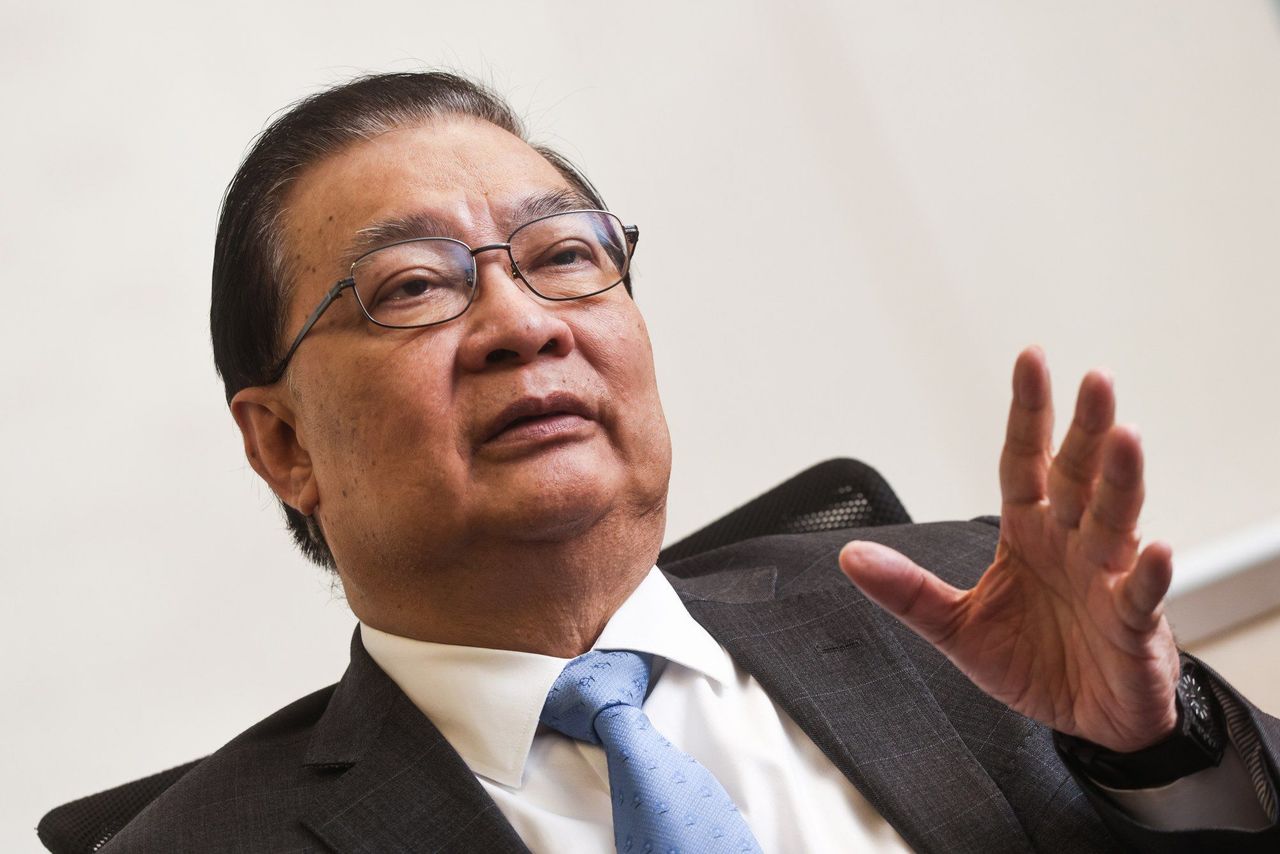

Professor Johannes Chan Man-mun, former law dean of the University of Hong Kong.

Professor Johannes Chan Man-mun, former law dean of the University of Hong Kong.

Professor Michael Davis, formerly a legal academic at the University of Hong Kong and now a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Centre in Washington, also expressed concerns that the “hostility” to legal input into national security cases “would just be the first step on a treacherous road”.

He argued Hong Kong courts could have benefited from the human rights expertise that overseas counsel could bring to them in national security cases.

“Tying defendants’ hands by denying them the best legal representation is surely not a way to deliver justice in Hong Kong,” he said.