Hong Kong News

Hong Kong start-up comes to the rescue of the world’s endangered corals

Vriko Yu Pik-fan was doing her weekly dive and research at a marine park in eastern Hong Kong’s Sai Kung area in 2014 when she made a startling discovery: a patch of corals had completely disappeared from the coastal waters within two months.

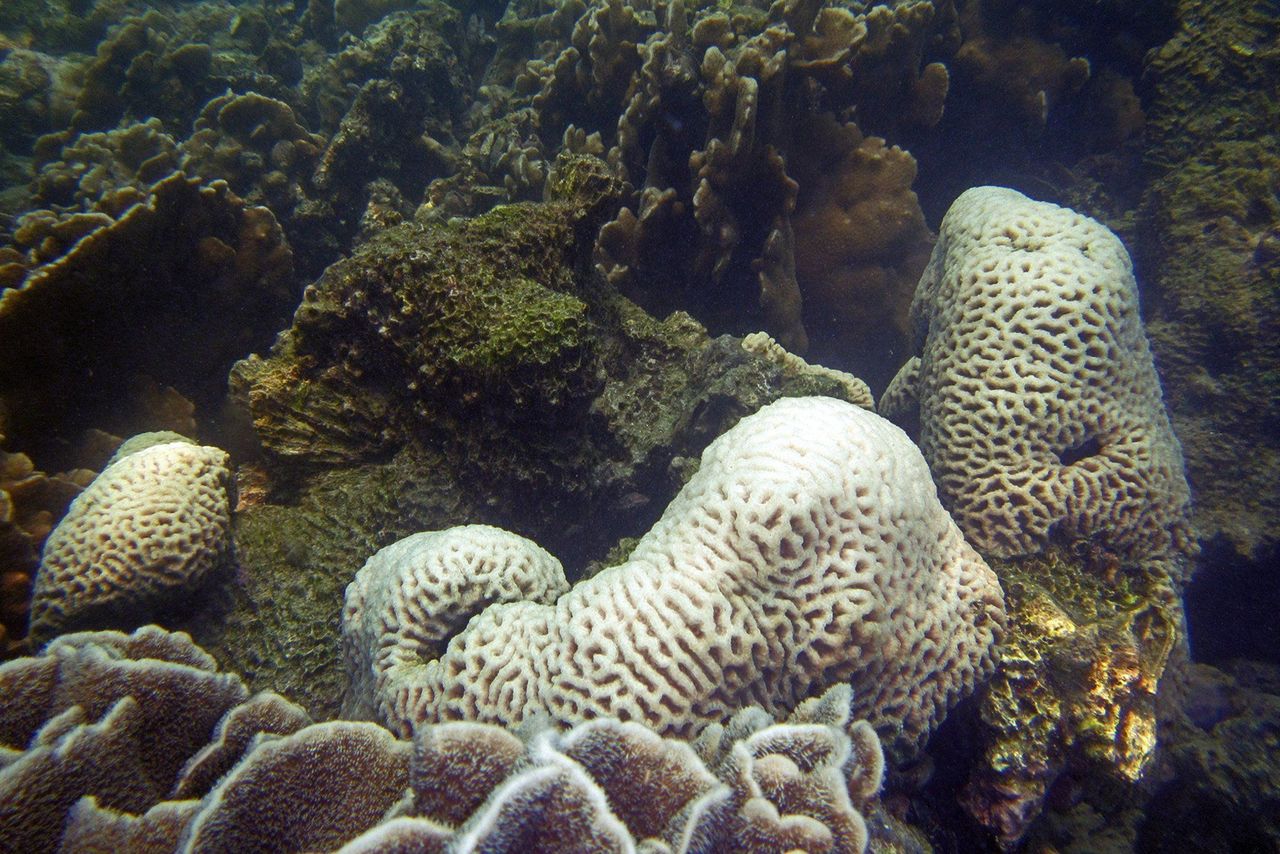

By the next year, 90 per cent of the Platygyra, the commonly found stony coral known as the brain coral, had been wiped off the sea floor of the Hoi Ha Wan Marine Park where Yu – a marine biologist completing her PhD at the University of Hong Kong – frequently dived for her research.

The “shocking experience” made Yu realise just how quickly climate change and rising sea temperature were gathering pace, and endangering Hong Kong’s fragile marine biodiversity.

That realisation spurred her into action. Using 3D printing technology, Yu co-founded a company called Archireef that creates terracotta reef tiles to help corals grow and survive once they are attached to the seabed. Archireef deployed 128 of its tiles at Hoi Ha Wan Marine Park for Hong Kong’s Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department in July 2020.

A patch of Platygyra brain corals at Hong Kong’s North Lantau area.

A patch of Platygyra brain corals at Hong Kong’s North Lantau area. Coral reefs are vital to the marine ecosystem. Besides providing crucial breeding ground and shelter for fish, reefs act as natural buffers against storms and surges, protecting an estimated 200 million people living along the world’s coastlines from violent weather, according to the Coral Reef Alliance. The annual economic value of seafood, tourism and recreation associated with reefs is estimated at US$2.7 trillion, according to the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network.

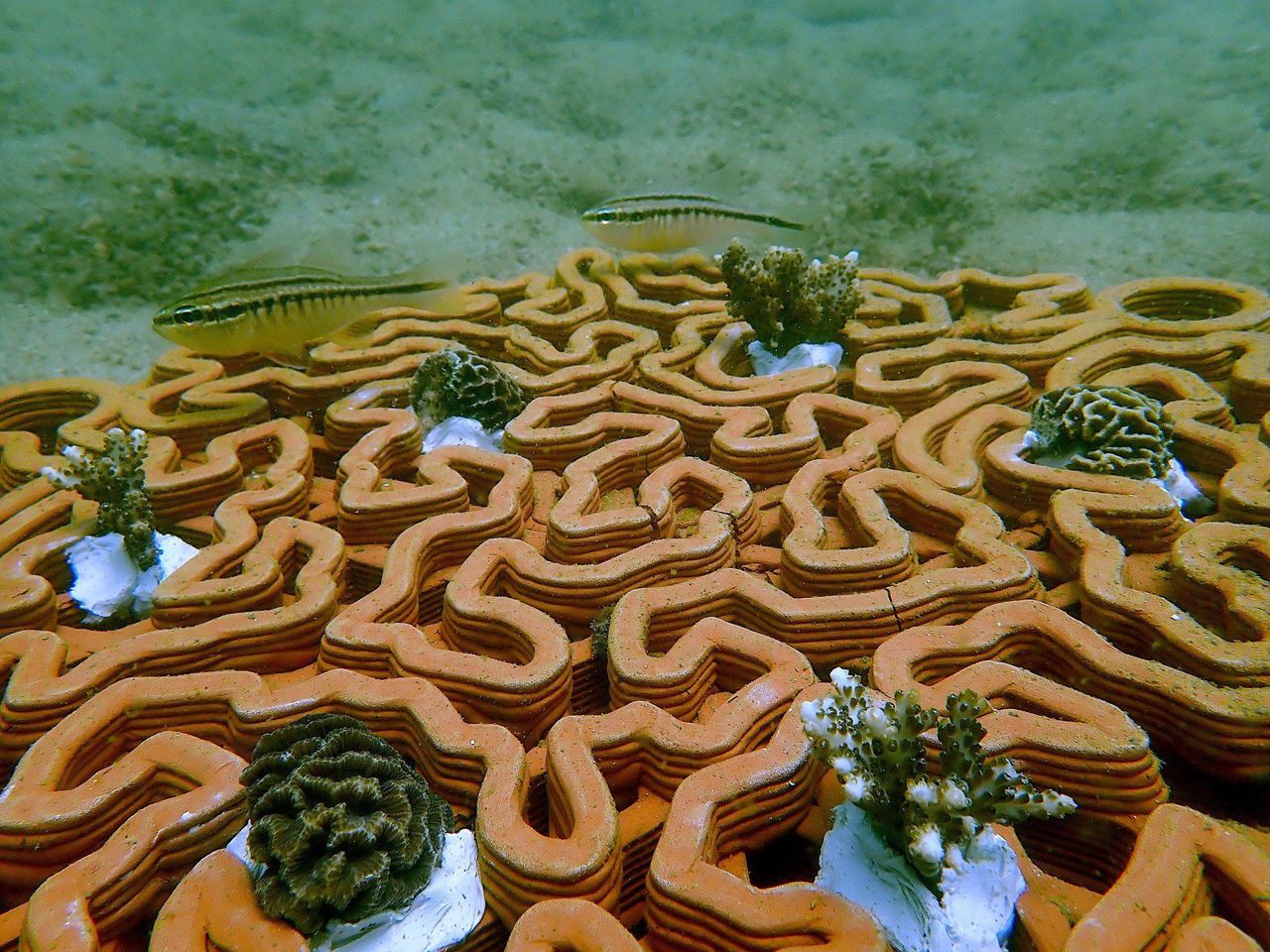

A terracotta reef tile, designed to mimic the appearance of a brain

coral so that its grooves and folds can provide habitat for marine life.

A terracotta reef tile, designed to mimic the appearance of a brain

coral so that its grooves and folds can provide habitat for marine life.

But reefs are also among the most fragile ecosystems, as corals are vulnerable to rising seawater temperatures and acidity. If the world’s temperature were to rise by 2 degrees Celsius from pre-industrial levels, it would wipe out 99 per cent of all remaining corals, according to a report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2018.

Archireef differs from other 3D printers that create reefs, such as Australia’s Reef Design Lab. Yu uses terracotta, a non-toxic material, and Archireef aims to be a nursery for corals to grow, instead of seeking to replace natural reefs.

In January, Archireef began deploying tiles to rebuild 40 square metres of artificial reefs seeded with rescued coral fragments in Abu Dhabi’s coastal waters, backed by the emirate’s sovereign wealth fund ADQ. The company also launched a facility in December with the capacity to print five reef tiles a day, using designs patented in Hong Kong, China, the Philippines and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

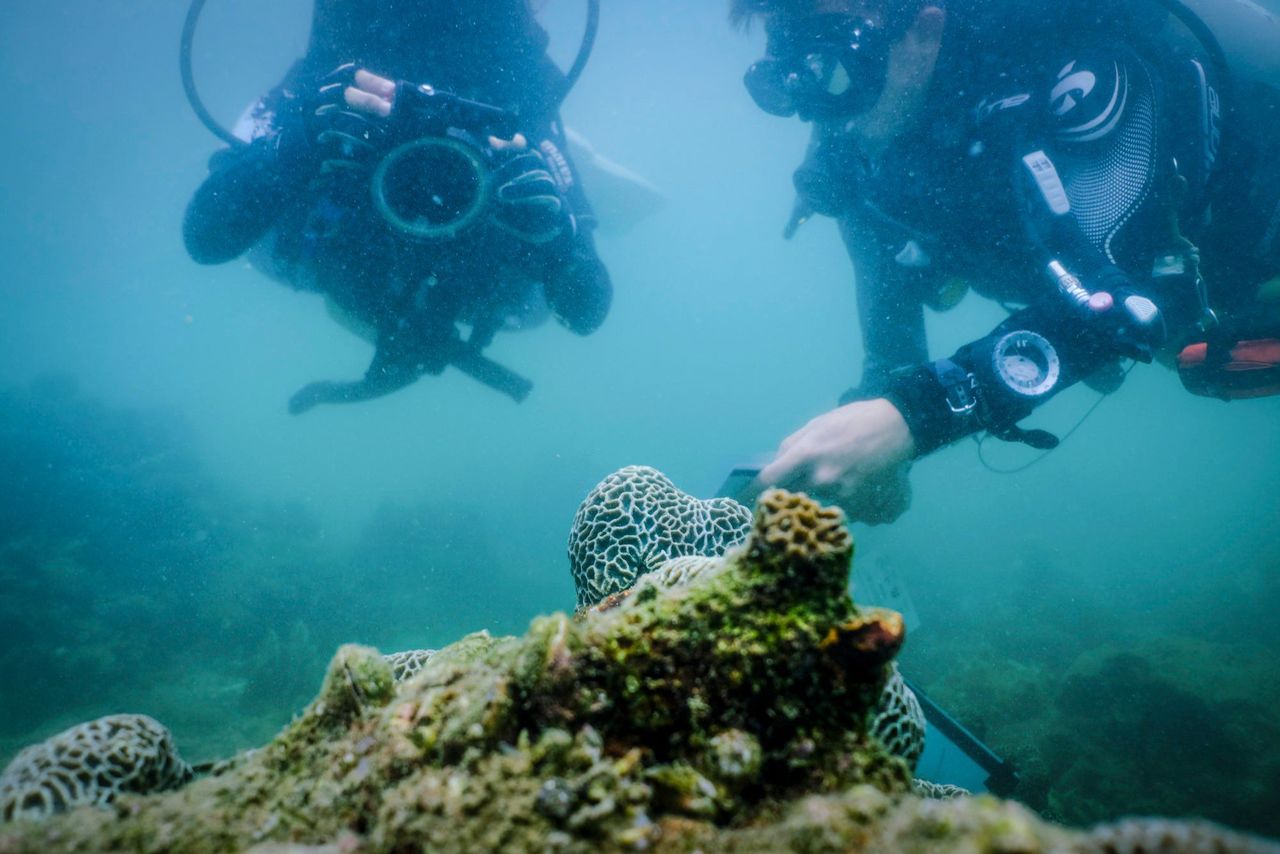

Yu-De Pei (right), coral researcher from Taiwan, and Vriko Yu Pik-fan

(left) checked the coral Platygyra on the seabed in Hoi Ha Wan on

December 5, 2018.

Yu-De Pei (right), coral researcher from Taiwan, and Vriko Yu Pik-fan

(left) checked the coral Platygyra on the seabed in Hoi Ha Wan on

December 5, 2018.

The reef tiles can be customised to suit local water conditions, helping to achieve up to a 98 per cent survival rate, four times more effective than traditional methods for restoring corals, Archireef said on its website.

They worked with Sino Group and Hong Kong’s Ocean Park last September, and recently expanded into the UAE to help save the Gulf nation’s degraded marine ecosystems.

Brought on by warmer oceans and climate change, the world’s coral reefs are at risk, experiencing the longest, most widespread and destructive bleaching from 2014 to 2017, according to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA).

Over 70 per cent of the world’s reefs experienced heat stress that was severe enough to trigger bleaching, or mortality, according to the NOAA.

“If we fail to stabilise the climate, the natural system will collapse,” said Anthony Hobley, executive fellow of strategic engagement at the World Economic Forum’s Centre for Nature and Climate, speaking at the Sustainable Innovation Forum at the 27th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP27) in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt in November.

“We have to decarbonise, and we have to stabilise the natural system,” said Hobley. “If we do one but not the other, we fail.”

Bleaching, when the corals expel the zooxanthellae algae living in their

tissues, putting them at risk of mortality, in the waters around Sharp

Island on July 31, 2014.

Bleaching, when the corals expel the zooxanthellae algae living in their

tissues, putting them at risk of mortality, in the waters around Sharp

Island on July 31, 2014.

At the 15th United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP15) in Montreal in December, a historic agreement was reached by over 190 countries to protect 30 per cent of land and water considered important for biodiversity by 2030. Currently, 17 per cent of terrestrial and 10 per cent of marine areas are protected.

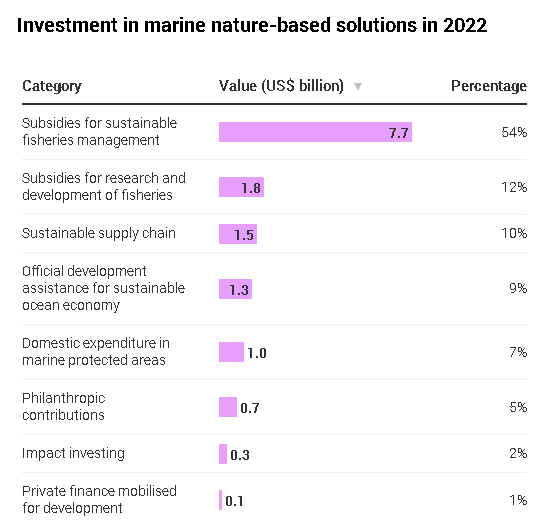

The framework also pledged to raise US$200 billion by 2030 for biodiversity from various sources, while phasing out or reforming subsidies that harm nature by at least US$500 billion per year.

The framework at COP15 also encouraged large transnational companies and financial institutions to assess, monitor and disclose biodiversity risks, impacts and dependencies.

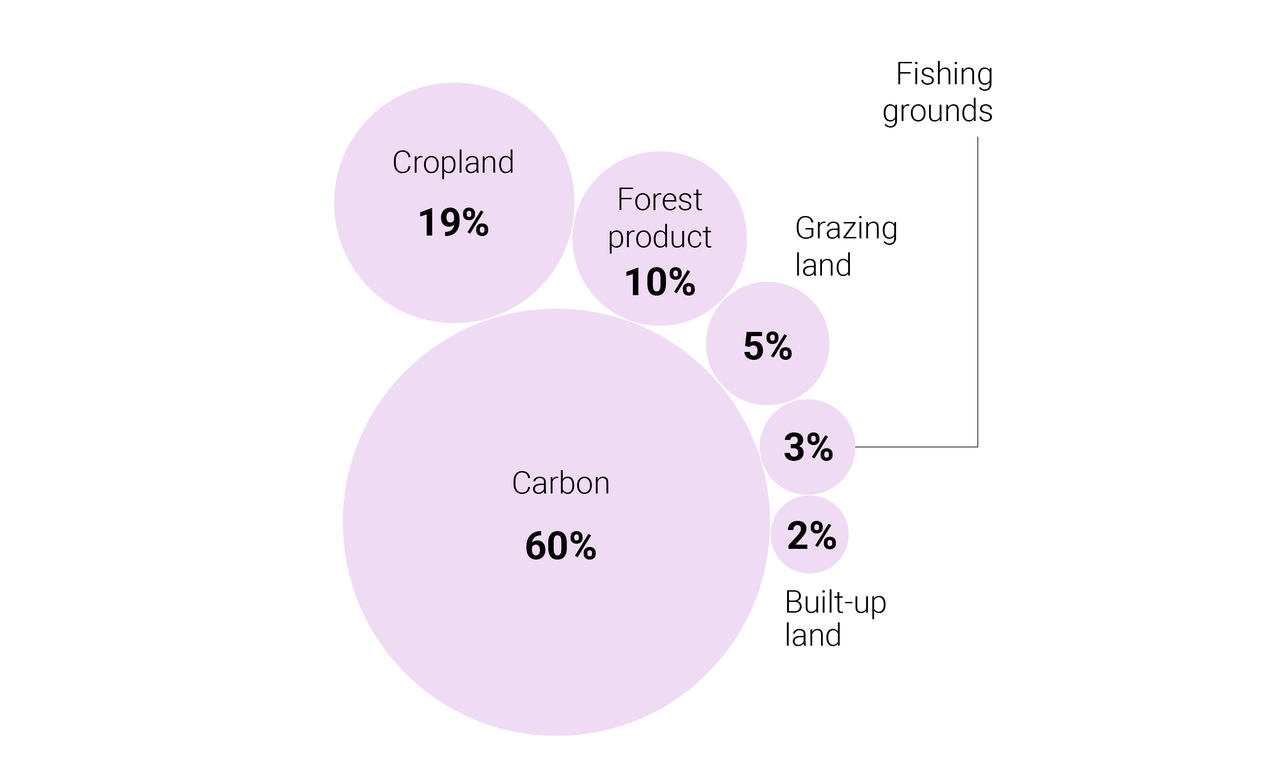

Source: WWF Living Planet Report 2022

Source: WWF Living Planet Report 2022

“COP15 garnered more public attention on biodiversity. Yet, there is a lack of universal guidelines on disclosure of biodiversity risks and opportunities at the moment”, HSBC’s head of global ESG research Chan Wai-Shin wrote in January. “Nature disclosure rules will be widely discussed, and ... adopted through 2023”.

Standard-setting bodies have been working on including disclosures related to biodiversity in their frameworks for businesses.

The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), a new body set up in late 2021 to consolidate various ESG reporting standards, announced at COP15 that it expected to address nature and biodiversity-related factors in its new draft disclosure requirements.

“Nature is one of the first victims of climate change, but it is also a provider of solutions. Nature-based solutions are here. We do not put value on them, but we will,” the ISSB’s chairman Emmanuel Faber said in his keynote speech at COP15’s Finance Day.

“We would immediately advance work to build from the climate standards to extend that immediately to connect with natural ecosystems, deforestation, water and biodiversity,” said Faber.

The ISSB would consider the work of the Task force on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), an initiative first announced in July 2020 for organisations to report and act on evolving ecological risks, in complementing their climate-related disclosures to address those related to natural ecosystems, Faber added.

The TNFD plans to release its framework for nature-related risk management and disclosures for market adoption in September 2023, according to its website.

Some companies recognise the importance of biodiversity impacts, and have already started to make disclosures as the first step to manage risks and opportunities.

Hong Kong and China Gas (Towngas) published a disclosure in response to the TNFD framework in November, which found that 11 of its 117 projects assessed were in proximity to key biodiversity areas, according to the gas distributor.

It would avoid areas rich in biodiversity, and take mitigating measures to reduce pollution and loss of topsoil during construction, Towngas said in its 2022 ESG report.

Insurers are also taking advantage of the business opportunity in providing coverage against biodiversity risks. Ping An Insurance now provides compensation when changes in the marine environment damage local species such as kelp, shellfish and algae, and lead to the weakening of the carbon sequestration capacity of the ocean.

However, a majority of companies worldwide are not translating commitments on biodiversity to action, according to the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), a non-profit organisation that runs the world’s environmental disclosure system for companies, cities, states and regions.

A pair of cardinal fish exploring a tile seeded with two species of the corals Platygyra and Acropora on August 21, 2020.

A pair of cardinal fish exploring a tile seeded with two species of the corals Platygyra and Acropora on August 21, 2020.

Of the 7,790 companies that responded to CDP’s questions on biodiversity in its 2022 questionnaire, only 31 per cent have made a public commitment or endorsed biodiversity-related initiatives, while another 25 per cent planned to do so within the next two years.

Meanwhile, 55 per cent of companies have not acted to take their biodiversity-related commitments forward in the last year, while 70 per cent of companies do not assess the impact of their value chain on biodiversity, the survey showed.

“In the past few years, we’ve all witnessed an improvement in how we view nature, and this very much made its way through public accounting, private accounting, economic output and realisation of the value of nature”, said Shereen Zorba, the head of the secretariat of the UN Science-Policy-Business Forum on the Environment, speaking at the Sustainable Innovation Forum 2022 at COP27 on November 10. “In terms of impact, we are far, far away from where we need to be”.

SWIMS scientists Vriko Yu and Philip Thompson planting coral fragments

onto terracotta tiles in Hoi Ha Wan Marine Park on August 21, 2020.

SWIMS scientists Vriko Yu and Philip Thompson planting coral fragments

onto terracotta tiles in Hoi Ha Wan Marine Park on August 21, 2020.

Nature-positive policies, or those that add value to nature, could attract over US$10 trillion in new business every year and create 395 million jobs by 2030, according to the WEF.

“Nature is the technology we have available for the next critical decade to help solve the net zero equation”’ said Joshua Katz, a McKinsey partner speaking during a November 12 webinar on protecting biodiversity and scaling nature-based solutions. “If you want to think about a cost effective way of capturing carbon or avoiding carbon loss, it is through natural systems”.

Oceans and forests help mitigate climate change with their capacity to capture carbon dioxide and store oxygen. One natural solution is afforestation, which establishes a stand of trees that can absorb and store greenhouse gases.

Children pose with 3D printed artificial reefs during the launch of

coral restoration project by Archireef, Sino Group and Ocean Park on

September 14, 2022.

Children pose with 3D printed artificial reefs during the launch of

coral restoration project by Archireef, Sino Group and Ocean Park on

September 14, 2022.

The ability of plantations to reduce carbon dioxide can earn the owners credits that are tradeable via voluntary carbon markets, once their sustainability and management standards are verified.

Forestry and land use-related carbon credits worth 227.7 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent were transacted globally in 2021, the largest category by volume and the second most expensive at US$5.80 per metric tonne, according to data from Ecosystem Marketplace.

While investors have been more familiar with forestry as a natural capital asset, there has been growing focus on “blue carbon”, including marine assets like seaweed, kelp and areas of marine land that are also sequestering carbon, said Mervyn Tang, head of sustainability strategy, Asia-Pacific at global asset manager Schroders.

The oceans represent over 70 per cent of the Earth’s surface and absorb around a quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions, acting as one of the world’s largest carbon sinks while also providing 17 per cent of the world’s protein, according to the UNEP.

“We expect biodiversity to retain its new-found prominence, with the role of oceans and nature-based solutions being increasingly recognised,” said HSBC’s Chan.

While biodiversity conservation has existed for decades, people have only started talking about quantifying and generating impact from biodiversity in recent years because of the technicalities of measuring it, said Archireef’s Yu.

“Biodiversity is a complex idea. We’re talking about all the animals that live in this area, including things that we see and do not see. So, inevitably, biodiversity is hard to measure,” said Yu.

Archireef is focused on collecting samples to examine the animals that live in the restored areas to create a biodiversity index which could potentially lead to biodiversity credits in the future, Yu added.

Similar to carbon credits, biodiversity credits are tradeable economic instruments that can be used to raise funds to finance biodiversity preservation projects and support actions to restore nature.

“What we invest in [climate solutions] today would collect at least 10 times more effectiveness, in terms of the ecological benefits, than if we invest 10 years later for the same amount”, said Yu. “This is the time for us to reverse the climate clock”.