Hong Kong News

Hong Kong Sars survivors turn trauma into Covid resilience, relive harrowing tales

So Chi-keung will never forget the month he spent with other Sars patients in the isolation ward of Hong Kong’s Princess Margaret Hospital 20 years ago.

“It felt like we were waiting for our turn to die,” recalled the former owner of a metalware factory. “Every day we saw someone die in the isolation ward, and we were told there was no cure.”

Twenty years after Sars hit the city, So Chi-keung still has fresh memories of the health crisis.

Twenty years after Sars hit the city, So Chi-keung still has fresh memories of the health crisis.

Known as Ah So to those who knew him in Sham Shui Po, he was 52 at the time with a wife and four teenage children. He worried about them all the time as he lay in his hospital bed. Fortunately, none of them contracted Sars.

His infection started with a high fever and coughing. Within a week, he was in hospital and struggling to breathe.

“I was exhausted just talking on the phone, like a dying old man,” recalled So, now 72. “The trauma, panic and anxiety still knock on my door from time to time, even after 20 years. I cannot control it, nor can I stop myself from falling into those traps again and again.”

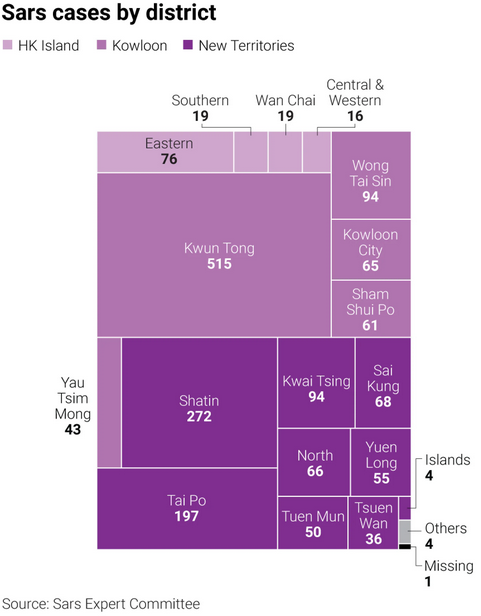

Princess Margaret Hospital in Kwai Chung, the city’s only infectious diseases hospital at the time, was the designated hospital to receive all new Sars patients from March 29 that year.

In the first week alone, almost 600 patients were sent there, including 45 who needed intensive care. Almost immediately, healthcare workers began falling ill and as the number rose, the hospital stopped admitting new patients on April 11.

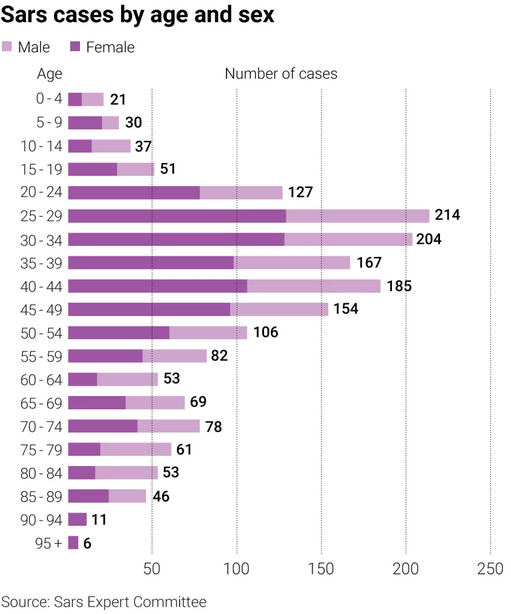

Over just three months, from late February to early June that year, 1,755 people in Hong Kong were infected and 299 died, including eight healthcare workers.

Sars, which emerged from mainland China, wreaked havoc on Hong Kong. The city was deserted. As people stayed home, the economy suffered. Schools closed for seven weeks.

Hong Kong’s “patient zero” was found to be a 64-year-old medical professor from Guangzhou, in neighbouring Guangdong province, who checked into the Metropole Hotel in Mong Kok on February 21, 2003, and fell ill.

Staff at the restaurant of the Metropole Hotel in April 2003.

Staff at the restaurant of the Metropole Hotel in April 2003.

He infected hotel guests who spread the mysterious disease to Hong Kong’s Prince of Wales Hospital when they sought treatment. Other infected guests took Sars from Hong Kong to other countries.

About three weeks later in mid-March, an ill man from Shenzhen visited his brother living at Amoy Gardens estate in Kowloon Bay, triggering a community outbreak.

Sars, eventually identified as a zoonotic disease transmissible from animals, such as bats to humans, infected more than 8,000 people in 37 countries and left almost 800 dead. Most cases occurred on the mainland, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Canada, Singapore and Vietnam.

A long road to recovery

So contracted the virus when he visited his uncle at Nethersole Hospital in Tai Po on April 1. His uncle was later found to have shared the ward with yet-undiagnosed Sars patients.

Although So wore a mask the whole time, he believed he was infected because he did not wash his hands when he changed his mask after the visit.

So recovered after a month in the isolation ward. He was pumped with steroids, which he said left him with a host of side effects, including chronic pain, muscle loss, hair loss and persistent shortness of breath.

His close brush with death also left him with lingering anxiety and depression, and he has seen a psychologist off and on over the years.

“Many Sars survivors I know are still suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, and they do not want to talk about it,” he said, “People cannot understand our pain because it’s not visible, and unlike Covid-19, we don’t have tens of thousands of people sharing the same experience.”

Facing mental and physical health issues after Sars made him choose early retirement later the same year.

Frontline nursing staff at the Prince of Wales Hospital in May 2003.

Frontline nursing staff at the Prince of Wales Hospital in May 2003.

“I struggled to climb onto the bus after leaving the hospital. It was just a small step, but my limbs were extremely weak,” he said. “And my arms could barely hold anything, not even a newspaper or grocery bag.”

His condition did not see significant improvement until four years later, when he discovered the power of nature therapy in a recreational area in Sham Shui Po.

“I went up to Bishop Hill with an old lady of the neighbourhood,” he said. “It was tedious to climb the slope, but I felt so much better afterwards. I believe the fresh air healed me.”

With his metalware background, he installed some fitness equipment at a hillside park and began exercising daily outdoors.

The small park, with parallel bars, swing, a trampoline, spin bikes and shoulder pulleys, has since become a neighbourhood landmark regularly used, especially by elderly residents.

“I’m glad that Sars did not kill me, that’s why I want to use my expertise and do good to others.”

So did not fall ill with Covid-19 during the pandemic over the past three years.

“Since I contracted Sars, I developed the habit of not touching my face when I am outside because our hands are full of germs, I also avoid going to crowded places,” he said, “I always remind people to follow these rules.”

He hoped Hong Kong would learn from the pandemic and devote more resources to improving public hygiene and the health of the elderly.

“We never know what will happen tomorrow, the best we can do is to do our part,” said So, a grandfather of three. “Now all I want is a healthy life.”

A pastor faces death in ICU

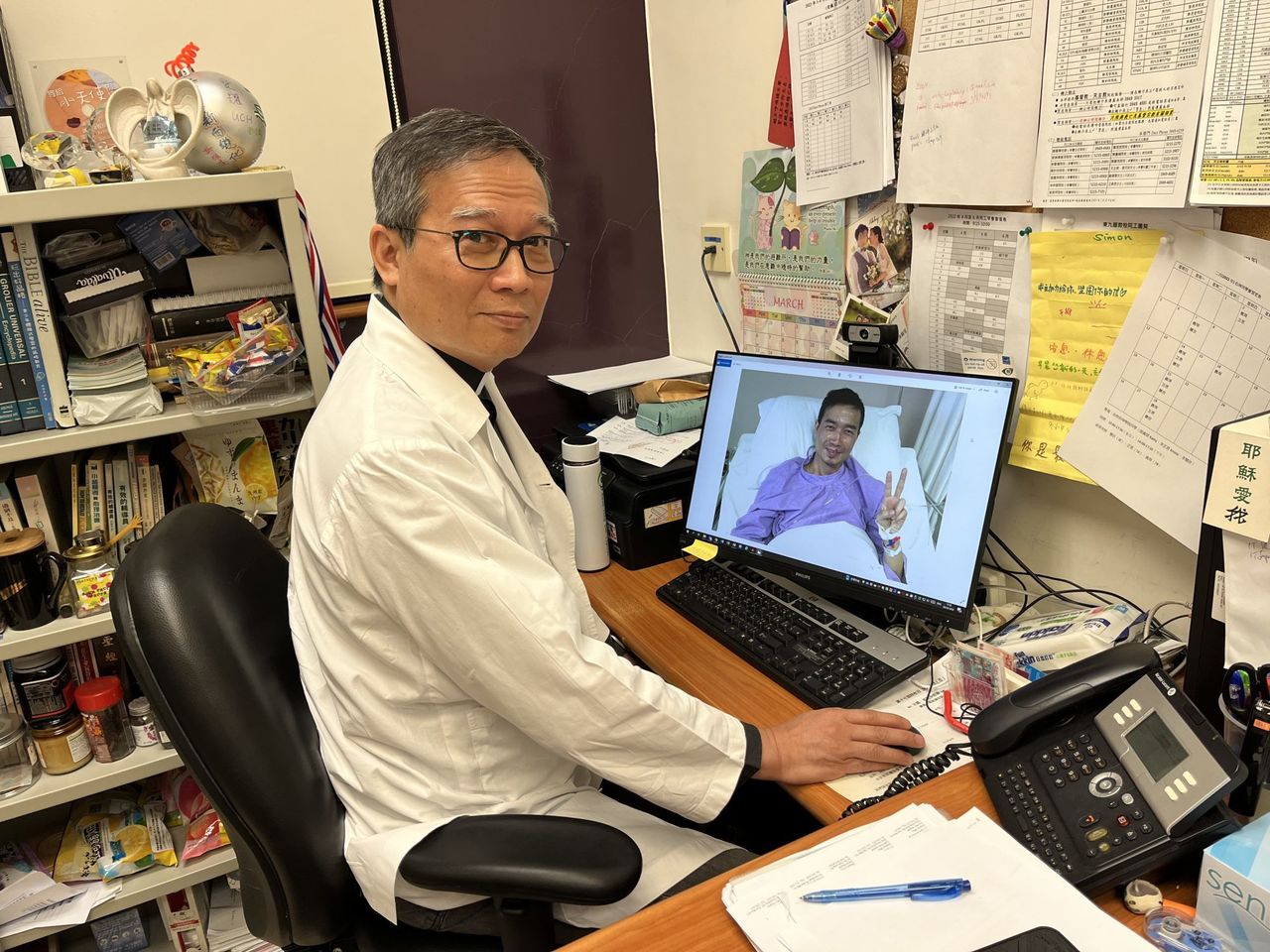

Lutheran Reverend Simon Tse Yiu-yeung is another Hongkonger whose life changed because of Sars.

A preacher at the time, he and his wife fell ill with Sars and for a few harrowing weeks, had to contemplate leaving their two young sons orphaned.

Reverend Simon Tse looks at a photo of himself leaving the ICU.

Reverend Simon Tse looks at a photo of himself leaving the ICU.

Ward 8A of Prince of Wales Hospital was another Sars epicentre where more than 200 healthcare workers, medical students, patients and visitors were infected.

In the early days of the epidemic, the government, health experts and the public were all clueless about what Sars was, or how it spread.

Tse contracted Sars after visiting a patient at the ward, and a few days later, his wife was ill too.

Tse was more severely affected and had to spend a week in the intensive care unit, while his wife remained in an isolation ward.

A resident at the Lower Ngau Tau Kok Estate in Kowloon Bay.

A resident at the Lower Ngau Tau Kok Estate in Kowloon Bay.

“In the intensive care unit, I saw some patients who were dead being packed away. The situation was chaotic. Some patients were mentally distressed and pulled their hair out as their blood spilled on the floor,” recalled Tse, now 61.

He had a close call too. He had a persistent high fever and suffered bouts of diarrhoea that would leave him struggling to breathe.

“I had diarrhoea two to three times a day,” he said, adding that a nurse would stand beside him, ready to intubate him. “The atmosphere was extremely anxious. Every time, I would wonder if I would survive.”

There was also the agony of being separated from his young sons, aged 10 and four at the time.

But he recalled: “My family was wounded by the experience. My wife and I suffered physically, while our two sons suffered mentally.”

Through the worst of his days in hospital, Tse made plans to have his brother take care of the boys in case he and his wife died.

Taoist priests conduct a ceremony at Amoy Gardens housing estate in May 2003.

Taoist priests conduct a ceremony at Amoy Gardens housing estate in May 2003.

He pulled through after a week at the ICU and two weeks in a general ward, while his wife was discharged after two weeks.

Tse, who was ordained that year, never forgot his time in hospital and the week he faced death in intensive care.

“I am very grateful for the healthcare system as the workers were my saviours. I kept wishing that I could fight alongside them,” he said.

His experience led him eventually to become chief chaplain at United Christian Hospital in 2014, working closely with patients, their families and the healthcare team.

When Covid-19 struck in early 2020, the authorities ordered a suspension of chaplaincy services at all public hospitals to curb the spread of the coronavirus.

Tse fought to keep the chaplaincy at United Christian Hospital running. His was one of the few hospital chaplaincies that provided spiritual care services after March 2020.

His Sars experience helped him understand the pain of patients isolated from family and the rest of the world.

“The pandemic cut off the relationship between patients and their families, which was heartbreaking,” he said.

Mourners pay their respects to Dr Joanna Tse, who volunteered to work with Sars patients.

Mourners pay their respects to Dr Joanna Tse, who volunteered to work with Sars patients.

He and his team stayed with the patients during their video calls with loved ones.

“We understood the patients’ condition and allowed them to talk about their worries,” he said. “We let them vent, and helped them find solutions. We catered to their spiritual needs.”

Sars also taught Tse that he should prioritise his family and make an effort to communicate emotional needs.

He and his wife began holding weekly chat sessions with their children, and this “family tradition” helped when Covid-19 arrived.

“We spent a lot of time praying, talking about our feelings, crying together and learning to put negative thoughts aside,” he said.

So when he contracted Covid-19 last September, everyone stayed calm.

“Sars changed my values, life direction and views on my service and family,” he said. “Crises can hone our ability to deal with challenges and persevere.”