Hong Kong News

Hong Kong’s future workforce needs liberal arts education to thrive

We live in a techno-feudal world. Seemingly all aspects of our lives are now constantly monitored, organised or controlled by tech companies. The rise of ChatGPT and other open-source AI applications further challenges human-technology relations by redefining the meaning of education, learning and creativity.

Although educators across the world are still trying to understand the pedagogical implications of these tools, the education sector has long fixated on science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) as the core of education for the future.

The abundance of success stories of programmers and software engineers at leading tech firms has fuelled the career dreams of younger generations. Schools and universities, meanwhile, compete to be recognised as the most innovative educational institutions with the best STEM programmes.

But even though many corporations today expect employees to possess high quantitative and digital literacy, they are also increasingly looking for people with social, emotional and cognitive skills including leadership, project management, critical thinking, continuous learning and empathy. These skills cannot be quantified, automated or substituted by machines, yet they are essential to organisational success.

In a world where economic growth is driven by knowledge and innovation, and with the major challenges facing humankind requiring solutions that transcend boundaries, it is more important than ever for the future workforce to possess technical knowledge as well as vital skills including creativity, interdisciplinary thinking and the ability to navigate through ambiguity.

A liberal arts education which helps students develop these vital skills is essential to training the future workforce. Even more important but often overlooked is the importance of a liberal arts education to building a pluralistic, resilient civil society.

Nonetheless, liberal arts subjects are considered by some to only be valuable to the elite or dismissed as guaranteeing poor pay. This is certainly understandable, given that graduates in applied subjects often enjoy an advantage over those in the liberal arts when they seek early career opportunities.

The value of the knowledge and skills liberal arts graduates have tends to be more manifest during the later stages of their career. The problem is not the value of liberal arts education itself but how it should be delivered in a 21st-century context.

Reiterating the importance of liberal arts education is not enough to make it relevant in Hong Kong. Guided by the narrative of catching up with Shenzhen in innovation and technology, the growth of a STEM education ecosystem has led the city to shun promoting liberal arts.

Not surprisingly, bright young people are piling into STEM programmes at the expense of liberal arts. Their preference is seen in last year’s Diploma of Secondary Education Entries statistics.

For elective subjects, more than 90 per cent of participating schools offered biology and chemistry, compared to 70 per cent for history, 30 per cent for Chinese literature and 7 per cent for English-language literature. While chemistry and biology each had around 12,000 students enrolled, geography only had about 8,000, history less than 5,000, Chinese literature 1,300 and English-language literature less than 300.

The skew of the distribution is a systemic phenomenon. Despite the 14th five-year plan and last year’s policy address outlining efforts to promote Hong Kong as a centre for international cultural exchange, there has been no mention of promoting liberal arts education.

If the government wants to nurture the arts and cultural talent in Hong Kong and the Greater Bay Area, it needs to promote a liberal-arts approach to education – one that provides students with a well-rounded understanding of the world from a young age.

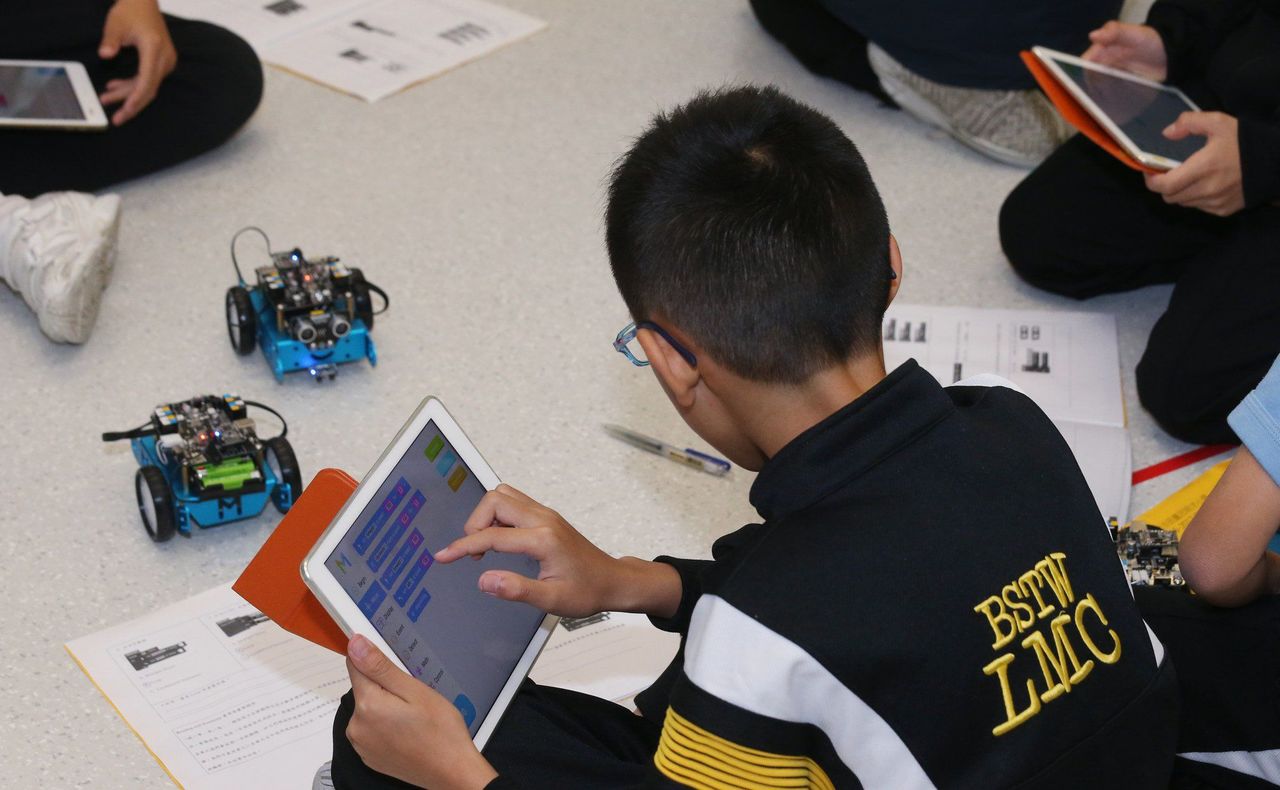

Students learn about robotics and STEM subjects at the Baptist Lui Ming Choi Primary School in Sha Tin in 2017.

Students learn about robotics and STEM subjects at the Baptist Lui Ming Choi Primary School in Sha Tin in 2017.

The idea isn’t to pit liberal arts against the STEM fields, and neither are they incompatible. The knowledge and skills a liberal arts education provides benefit the flourishing of STEM talent.

Nonetheless, rather than continue with an outdated, rigid pedagogy in the classics, a re-envisioning of liberal arts education is needed if we aspire to be a global hub of knowledge, creativity and innovation. In a wired world – where automation and machine learning algorithms are becoming more sophisticated – there is a growing need for people who possess skills that cannot be fully automated or replicated by machines.

A liberal arts education offers just that. While many people do believe in the value of liberal arts education, one must reimagine what it means and how it should be delivered to remain relevant in the 21st century.