Hong Kong News

Hong Kong’s Covid-19 patient quarantine rule ‘unethical’, expert says

A leading Hong Kong health expert has labelled a new 14-day quarantine requirement for recovered Covid-19 patients as “unethical”, while a major patients’ rights group has suggested the government should offer cash payments for low-income residents forced to undergo it.

Professor Benjamin Cowling of the University of Hong Kong, a top epidemiologist in the city, on Wednesday launched a scathing attack on the policy change – aimed at easing Beijing concerns and reopening the border – branding it “ridiculous” and “unethical”.

Speaking out on Twitter, Cowling said the policy was a “waste of resources and actively harming the patient with no community benefit to offset against”.

“That makes it unethical surely,” he said. “I hope it doesn’t also apply to ‘re-positives’, that would be even more ridiculous”.

The Patients’ Rights Association, a group championing medical causes with a focus on underprivileged residents, meanwhile, warned that authorities risked discouraging low-income patients from getting tested for fear of being locked up for a sustained period of time without pay.

“The government should remove economic disincentives for poor people to seek medical help, either in the form of direct subsidies, or by asking the Community Care Fund or charities to step in to help,” the association’s Tim Pang Hung-cheong told the Post on Wednesday.

“The city’s low-income residents who are just getting by cannot afford to lose a day’s income, and might even lose their jobs due to a long absence from work.”

The developments came as Hong Kong on Wednesday confirmed five new Covid-19 infections, all imported and fully vaccinated, taking the local tally to 12,335 cases, with 213 related deaths.

The University of Hong Kong’s Ben Cowling (right) has said a new 14-day quarantine has ‘no community benefit’.

The University of Hong Kong’s Ben Cowling (right) has said a new 14-day quarantine has ‘no community benefit’.

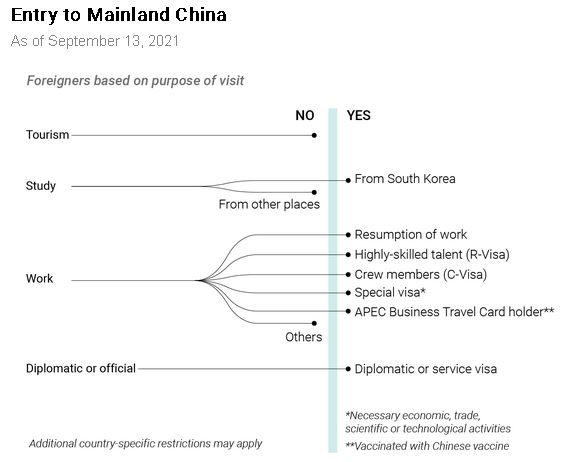

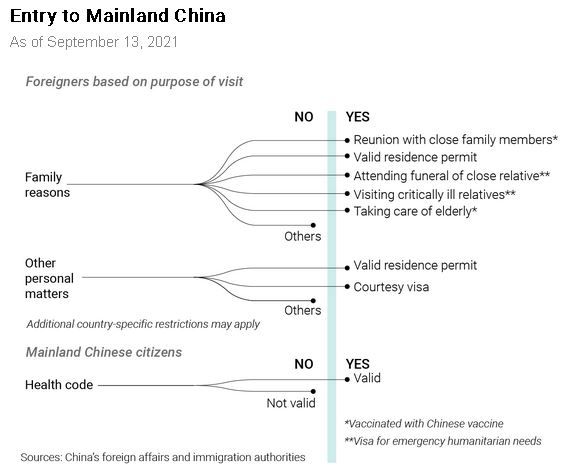

City officials have been engaged in a prolonged bid to secure approval from Beijing for the resumption of quarantine-free, cross-border travel.

But the first meeting involving experts and officials from both sides last month ended with little progress and no timetable, only suggestions aimed at improving the city’s anti-pandemic controls, including tightening patient discharge rules.

On Tuesday, Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor announced a raft of major changes, including revoking quarantine exemption privileges to most groups previously deemed essential for business and the city’s daily operations.

Another key change centred on tightening discharge conditions for infected people from Wednesday, allowing them to leave hospital only after testing negative twice. They must then spend an additional 14 days in quarantine at a separate facility – a policy aligned with the mainland’s.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam this week said a raft of policy changes were

aimed at easing Beijing concerns over the reopening of the border.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam this week said a raft of policy changes were

aimed at easing Beijing concerns over the reopening of the border.

Explaining the move, a government spokesman said the tighter rules were in keeping with the city’s zero-Covid stance and would “further reduce the risk of such patients bringing the virus into the community to a minimum”.

He added: “It will also lower the risk of the virus spreading in the community due to possible repositive situations.”

There are currently 49 Covid-19 patients in public hospitals in Hong Kong. Those who meet the new discharge criteria will be transferred directly to the North Lantau Hospital Hong Kong Infection Control Centre to carry out the two-week quarantine and undergo health monitoring.

To be released, symptomatic patients must have normal body temperature for more than three days, significant improvement in clinical symptoms, and two negative coronavirus tests taken at least 24 hours apart. They must also go at least 10 days without displaying any symptoms.

Asymptomatic patients must have two negative Covid-19 tests taken at least 24 hours apart and have a minimum of 10 days pass after their first positive result.

Under the previous regime, patients were allowed to leave hospital if their viral load was low enough that they were considered unable to infect others, and they were not required to test negative.

Pang said he understood the public was anxious to get the border reopened for travel and economic reasons, but stressed a fine balance needed to be struck, and the latest measures risked deviating too far from the protection of patients’ rights.

Alex Lam Chi-yau, chairman of the NGO Hong Kong Patients’ Voices, also acknowledged the public interest involved, but warned the new rules could “further deter” businessmen and other local residents from coming to the city, as a positive coronavirus test result could land them in a long hospital confinement and quarantine.

Respiratory medicine specialist Dr Leung Chi-chiu, however, told a radio programme that the previous discharge rules could allow false-negative patients back into the community, and were set at a time when public hospitals were coping with too many cases during previous coronavirus waves.

But Cowling, the epidemiologist, said he believed the policy was not medically justified.

“They are no longer a threat if they are discharged,” he said. “There has never been any report of any recovered case triggering a community outbreak, and that’s the same as the rest of the world.”