Hong Kong News

Hong Kong pushing ahead with legal aid overhaul, despite lawyers’ concerns

A proposed overhaul of Hong Kong’s legal aid system that some fear could curtail government critics’ access to quality representation may be implemented as early as the end of the year, with authorities standing by their decision not to hold mass consultations on the changes.

The city’s two biggest legal bodies said on Tuesday that they were given little time to study the contentious proposal, which would, among other changes, do away with the ability of indigent defendants to pick their own lawyers and slash the number of judicial reviews attorneys can argue in a year.

The overhaul, one prominent lawyer said, could ultimately disadvantage plaintiffs seeking to challenge the authorities in court.

The government, however, has been clear that it intends to push the overhaul through, defending its decision to conduct only limited consultation by insisting the changes are minimal and do not require widespread feedback.

Chief Secretary John Lee Ka-chiu wrote in a blog post on Tuesday that the government hoped to fully implement the changes by year’s end.

The overhaul, he said, would prevent a small group of lawyers from monopolising cases subsidised by taxpayers’ money, while the Legal Aid Department would ensure applicants’ were assigned competent counsel to safeguard their fair trial rights.

Speaking before a Legislative Council session scrutinising the proposal on Tuesday, Daniel Cheng Chung-wai, director of administration for Lee’s office, was even more blunt about the timeline: “If you ask if we are desperate to [make these changes] – yes, we are. Actually, we would like to do it as soon as possible.”

It first emerged on Friday that Lee’s office and the Legal Aid Department were seeking to axe legal aid claimants’ long-established discretion in choosing their own lawyers in criminal cases, while also limiting lawyers’ ability to take up judicial reviews.

The overhaul would see solicitors barred from arguing more than five judicial reviews per year, or three for barristers – down from 35 and 20, respectively. It would also impose more modest reductions on the number of civil cases they can accept.

The changes were prompted by dissatisfaction among the pro-establishment camp that cases involving opposition activists and protesters who required legal aid were often argued by the same group of lawyers.

The legal community has countered that for defendants, the choice of counsel is a matter of trust, and that judicial review in particular is a highly specialised field. The changes, they said, could have the effect of undermining their clients’ rights at the expense of politics.

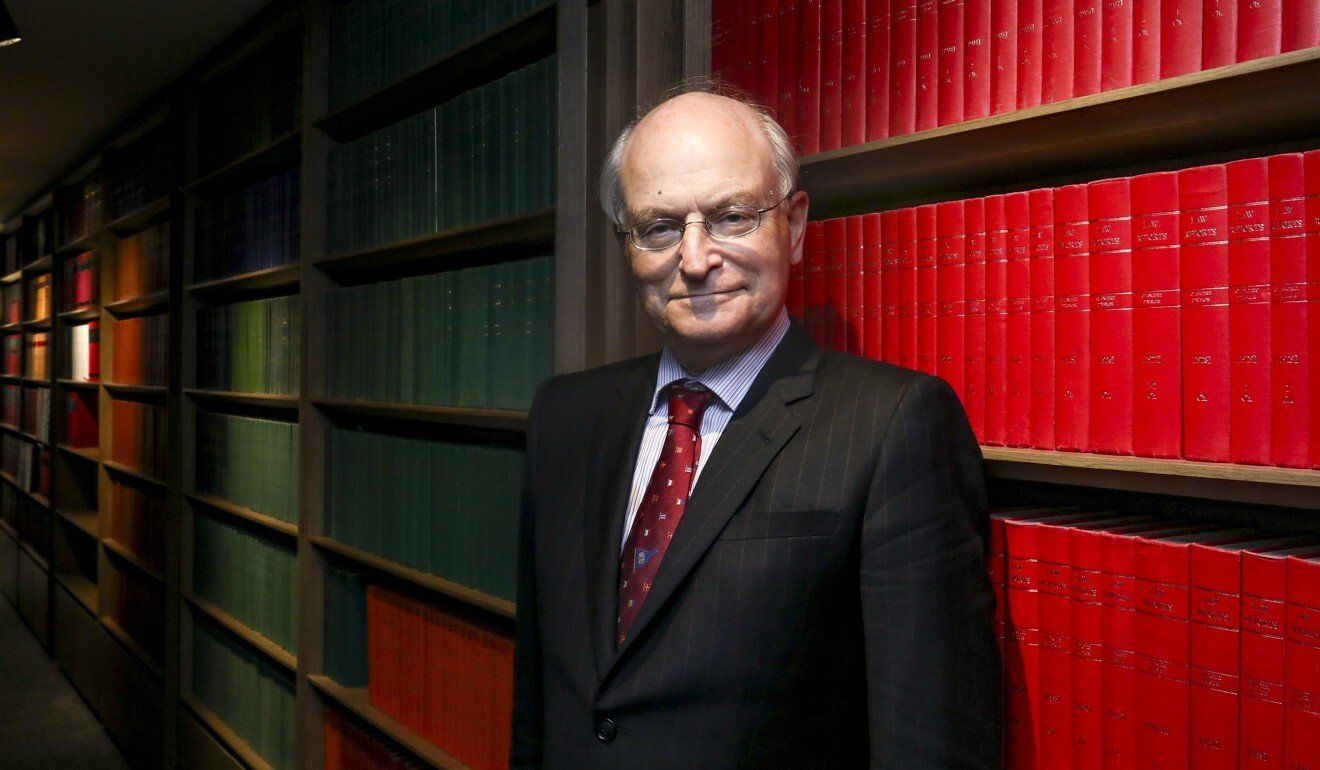

Paul Harris, a judicial review specialist and the head of the Bar Association, told the authorities during Tuesday’s Legco justice panel hearing that his preliminary view was that the proposal would require a delicate balance between providing new opportunities to barristers wanting to break into the field and safeguarding the quality of counsel available to clients.

He also reminded the authorities that their changes must comply with the city’s mini-constitution, the Basic Law, which guarantees fair legal representation. “We think it really has to be looked at carefully,” he said, adding that barristers’ bodies intended to submit detailed suggestions later.

Paul Harris, the newly elected chairman of Hong Kong Bar Association,

poses for the photo during an interview in Admiralty. 22JAN21

Paul Harris, the newly elected chairman of Hong Kong Bar Association,

poses for the photo during an interview in Admiralty. 22JAN21

Johnny Ma Ka-chun, the group’s Honorary Secretary, said he was concerned that should the changes take effect, there would not be enough experienced barristers to meet demand among those seeking to lodge legal challenges. The government, on the other hand, being more than capable of paying its own legal fees, would be unaffected, he added, leading to a discrepancy in the quality of representation.

“Whether the quality of legal representation would affect the court in arriving at the most accurate ruling would be one of the points concerned,” he said.

Stephen Hung Wan-shun, who chairs the Law Society’s criminal law and procedures committee, argued that if the Legal Aid Department were to introduce a mechanism for rejecting a defendant’s application for the lawyer of their choice, it should also draw up a set of objective criteria for doing so.

However, Cheng, from the Chief Secretary’s Office, insisted the changes were minor as they would not require legislative amendments, and because in the case of judicial reviews and civil cases, they were merely adjustments to already existing quotas.

Pro-establishment lawmakers, meanwhile, welcomed the proposal on Tuesday, with Holden Chow Ho-ding, a lawyer and the vice-chairman of the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong, saying: “Public money should not be monopolised by a small number of lawyers.”

Lawmaker Paul Tse Wai-chun, also a lawyer by profession, reminded the public that middle-class defendants, who did not qualify for legal aid, were not always able to hire the lawyers of their choice either due to monetary constraints.

“This way, people might appreciate how fortunate they are to get legal aid,” he said.

The Legislative Council has been all but devoid of opposition voices for nearly a year since the bulk of the camp resigned en masse and one of two remaining independents was ousted in August.