Hong Kong News

Hong Kong plans major shift with proposed Northern Metropolis

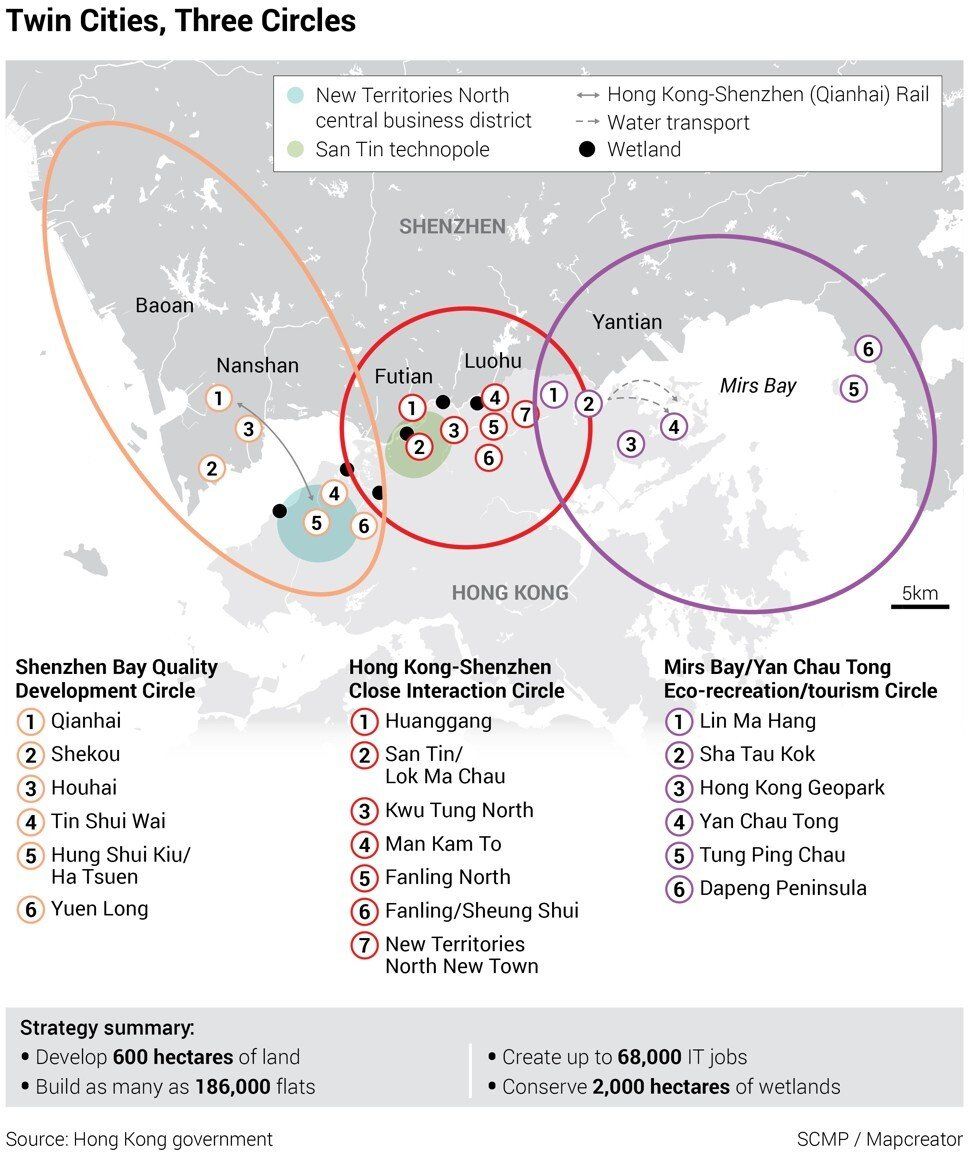

Hong Kong’s border area with mainland China will be built into a new Northern Metropolis of 2.5 million people in 20 years, including a “Silicon Valley” that will closely interact with neighbouring Shenzhen, according to a blueprint laid down by Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor in her policy address on Wednesday.

The scheme, repackaged and expanded from an existing new town plan, is seen as a major strategic change for development, moving the centre away from Hong Kong Island to the north, to integrate the city into the latest national development plan.

It would involve a new cross-border railway linking the city to the Qianhai economic zone in Shenzhen, and an extension of a local northern rail link that would stimulate development across Hong Kong’s rural hinterland.

The Qianhai economic zone in Shenzhen.

The Qianhai economic zone in Shenzhen.

The plan will also involve government resumption and conservation of about 2,000 hectares (5,000 acres) of ecologically important sites including wetlands, some of which are likely to be held by major developers.

While some observers noted the political reality of the city following the national strategy to develop the border area, others questioned the burden on public finances, as the government had also been pursuing a billion-dollar reclamation project to the west of Hong Kong Island.

Announcing the Northern Metropolis Development Strategy, Lam said: “It is the most vibrant area where urban development and major population growth of Hong Kong in the next 20 years will take place.

“With as many as seven land-based boundary control points, the Northern Metropolis will be the most important area in Hong Kong that facilitates our development integration with Shenzhen and connection with the Greater Bay Area.”

The metropolis will include existing new towns in Tin Shui Wai, Yuen Long, Fanling and Sheung Shui and their neighbouring rural areas, as well as six new development areas under planning or construction.

Upon full development of the entire Northern Metropolis, a total of 905,000 to 926,000 flats, including the existing 390 000 homes in Yuen Long and North districts, would be available to house a population of about 2.5 million, she said.

The total number of jobs would increase substantially from 116,000 at present to about 650 000, including 150 000 jobs related to innovation and technology.

A 1,100-hectare “technopole” would be built in San Tin, dubbed “Hong Kong’s Silicon Valley”, which would be a community for IT talent and provide a total gross floor area as big as 16½ Science Parks.

To improve transport, the Hong Kong-Shenzhen Western Rail Link, to run between Hung Shui Kiu new town and Qianhai, would be built, along with four other local railway projects that would link more rural spots in the northern New Territories.

Lam dismissed concerns about costs. “I can share my experience with everyone. The most profitable thing in Hong Kong is land. It is impossible for us to lose money during the process of developing land,” she said.

The chief executive also said the project was not something one administration could deliver, but “a government that works for the best interests of Hong Kong will have to go down this path”, adding she was not worried the next leader would change the plan.

Lam also said that to tackle the severe shortage of land, both the new Northern Metropolis plan and her own brainchild, Lantau Tomorrow Vision, a massive reclamation project in waters to the east of Lantau Island, would be needed.

“We cannot forgo the reclamation,” she said, adding that commencement of the Lantau project was likely to be pushed forward by a year, to 2026.

As part of the northern plan, ecologically important wetland sites would be resumed by the government for conservation, including Fung Lok Wai and Nam Sang Wai, where CK Asset and Henderson Land Development respectively have land and residential projects planned.

But Ling Kar-kan, the government’s strategic planning adviser for Hong Kong/Shenzhen cooperation, would not say whether those plots would be taken back.

Land at existing boundary crossing points at Lo Wu and Man Kam To would be redeveloped for housing and commercial development, he added, as their cargo functions would be taken by other ports. He added that future residents would be able to take up jobs in the area without having to commute to Kowloon or Hong Kong Island.

Ryan Ip Man-ki, head of land and housing at think tank Our Hong Kong Foundation, welcomed the proposal to urbanise the New Territories and provide another land supply source aside from the Lantau scheme.

The Heung Yuen Wai boundary control point.

The Heung Yuen Wai boundary control point.

He said it was time to move away from the “Central perspective” focusing on both sides of Victoria Harbour to a “regional vision” to seize opportunities from Hong Kong-Shenzhen economic synergy. He said development density should be aligned with that of old urban areas.

Francis Lam Ka-fai, chairman of the Institute of Surveyors’ planning and development division and housing policy panel, said he believed there might be challenges in terms of matching jobs to future residents, as not everyone would be qualified to work in the IT or innovation sector. He said traditional trades should still be promoted to provide jobs.

The Real Estate Developers Association said it would collaborate with the government on the plan.

Rosanna Tang, head of research for Hong Kong and the Greater Bay Area at Colliers, said the scheme would be a “big game-changer” and narrow the property price gap between the New Territories and urban centres in the long run.

Edwin Lau Che-feng, founder and executive director of conservation group The Green Earth, expressed some scepticism.

“I hope the government is truly doing this for conservation and not as a trade-off for development,” he said, adding dump sites and car parks should be used first for redevelopment.

He said the Northern Metropolis development would be much more favourable than reclaiming land for the Lantau plan if the government could balance environmental with social and economic needs.