Hong Kong News

Hong Kong organ donation register hit by wave of withdrawal applications

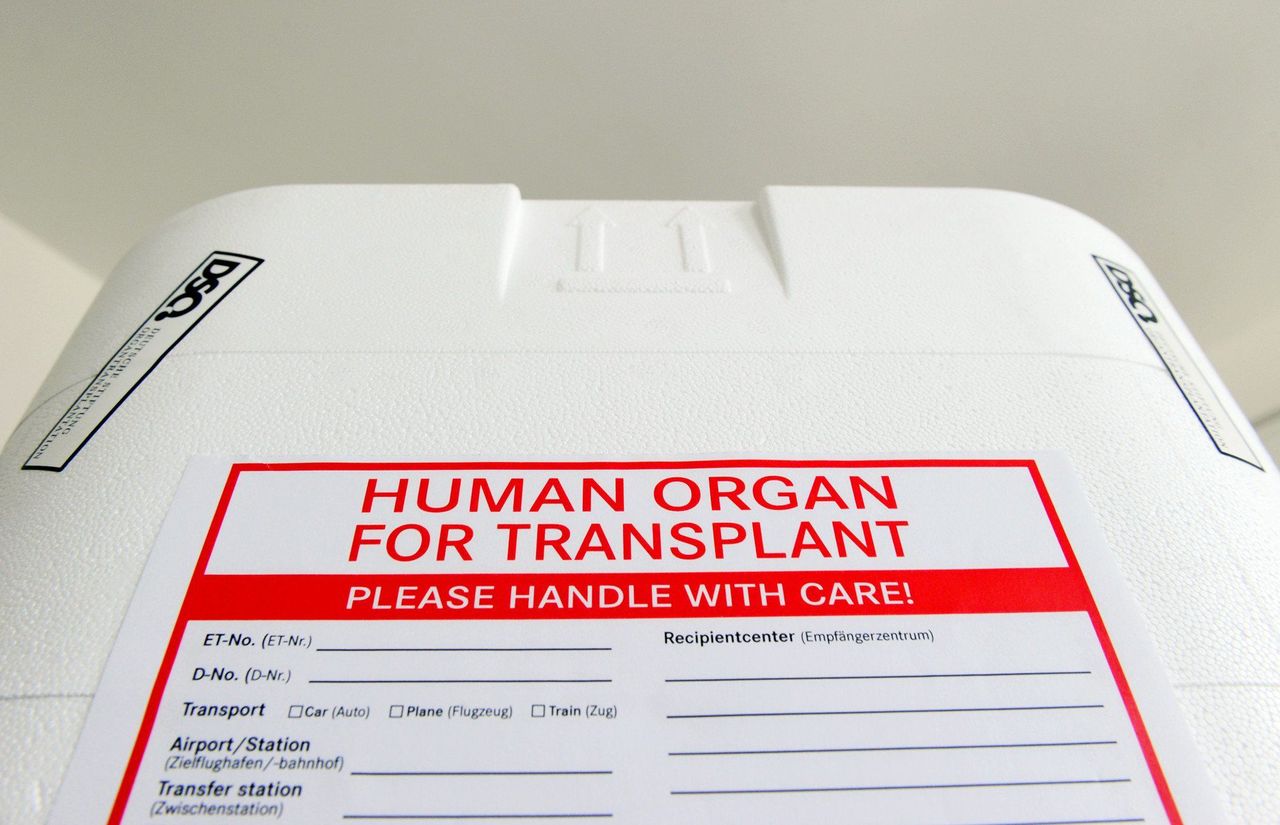

Hong Kong has recorded an unusual rise in the number of residents applying to withdraw from the city’s organ donor register since December, health authorities have revealed, with the increase starting after the government said it hoped to establish a cross-border donation mechanism.

More than half of all attempted withdrawals were invalid as the applicants had not registered in the first place or repeatedly made requests to leave the scheme, the Health Bureau said on Monday, warning that “a small group of people” could be trying to jeopardise hard-earned support for organ donation.

According to bureau data, 5,785 withdrawal applications have been received since December, the month a Hong Kong baby girl suffering from heart failure received a donated organ from mainland China, in the first arrangement of its kind.

Cleo Lai received a heart from a donor in mainland China.

Cleo Lai received a heart from a donor in mainland China.

The figure for the five months to April was “significantly higher than that recorded in the past” as 2,905 of the applications were found to be invalid, the bureau said. In February alone, the percentage of invalid withdrawal applications was as high as 74 per cent.

From 2018 to 2022, the number of withdrawals annually ranged from 266 to 1,068.

“It cannot be ruled out that a small group of people have intentionally made withdrawal attempts with the aim of disrupting the representativeness of the Centralised Organ Donation Register and increasing the administrative burden on government personnel,” the bureau said.

The government strongly condemned “such utterly irresponsible behaviour”, it added.

It said some people had “wantonly vilified” the significance of the mechanism, as well as “despising” ties between residents on both sides of the border and the “selfless acts” from the mainland that had saved the lives of Hong Kong patients.

The bureau urged the public “not to let a small group of people with ulterior motives jeopardise the hard-earned atmosphere in support of organ donation over the years”.

It said some internet users had recently promoted the idea that organ donors should scrutinise the identity of recipients and urged others to withdraw from the register.

A check by the Post on Monday found that internet users were posting a link for cancelling organ donation registration on LIHKG, a popular Hong Kong online forum.

But under international practice, donors or their family members cannot designate specific recipients or ask for any identity screening. The identity of recipients will also not be made known to family members of donors beforehand.

The authorities said such a mechanism was in place to ensure no beneficial interest or discrimination would exist between donors and recipients.

After a heart was donated to four-month-old Cleo Lai Tsz-hei in December, Hong Kong health authorities said they were exploring the setting up of a standing organ transplant mutual assistance mechanism with the mainland.

The plan under consideration would be a second-tier mechanism which can be activated immediately once suitable patients cannot be identified for any organ donated on either side of the border and local matching is unsuccessful.

The government said it was examining the proposed mechanism with the mainland to align technical requirements, criteria and operational procedures, and to ensure that organ donation was conducted in a legal, fair, equitable and safe manner.

A delegation led by Hospital Authority chief executive Dr Tony Ko Pat-sing visited Guangdong province over the past weekend to learn about organ transplant procedures on the mainland.

Dr Chau Ka-foon, honorary president of the Hong Kong Transplant Sports Association, said that while it was unknown if those applying to withdraw from the register were unsatisfied with the proposed mechanism, it was possible people might not be familiar with the mainland healthcare system and develop distrust towards it.

She said the proposed mechanism would not affect Hong Kong’s current donation system as it would only be triggered when organs could not be matched to local patients.

A doctor has urged the public to think about patients awaiting transplants.

A doctor has urged the public to think about patients awaiting transplants.

Chau said the government should put in more effort in explaining how the mechanism would work to dispel misconceptions.

“Most importantly, the government should clarify how Hong Kong and the mainland will collaborate in order to give Hongkongers peace of mind,” she said.

“They should explain clearly how the mechanism operates and prevent people from having the false assumption the organs will be given to the mainland without reasons.”

Chau said it was extremely rare that organs in Hong Kong could not find suitable recipients.

She said some donated hearts and lungs in the past could not be transplanted because only one doctor was in charge of such operations in some hospitals and they were on leave or overseas. It also occurred when blood types or body sizes were a mismatch.

She urged the public to think about the patients awaiting transplants.

“We should grasp any opportunity that can increase their chance of getting a transplant,” she said. “We should not let rumours or misunderstanding affect our intention to help others.”

John Burns, honorary professor at the department of politics and public administration at the University of Hong Kong, described the mechanism as “positive” and “a step forward”, but refrained from interpreting people’s motivation for withdrawing from the register.

But he said those who had applied for withdrawal even though they had never opted in for organ donation could be making a political statement.

Burns said the government’s statement had used “the strong absolutist language” employed by the security services in the past such as “wantonly vilify” and “despising” as though they were discussing terrorists and foreign colluders.

He said rather than strong condemnation, more education and persuasion were needed.

“Organ donation is a serious business and many people’s lives depend on it. The system must be nurtured, supported, enlarged and strengthened,” he said.