Hong Kong News

Hong Kong needs to invest in climate resilience, not artificial islands

In recent discussions on the development of the Kau Yi Chau artificial islands, better known as the Lantau Tomorrow Vision, experts have called for the correct science to be used to assess Hong Kong’s risk of a sea level rise from climate change.

As an international research centre focused on health emergencies and disaster-risk management, we know that the risk of flooding disasters from climate change, including storm surges and rising sea levels, make up the key hidden cost in the development of artificial islands – and feel that precious resources must be better channelled to enhance our city’s resilience to disasters.

Since UN members adopted the Hyogo Framework for Action 2005-2015, the global focus has shifted from post-disaster rescue to preventing new risks, reducing existing risks and strengthening resilience – through cost-effective investments to prevent social, economic and environmental losses.

In repeatedly highlighting the need to avoid creating new risks, the successor Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 further recognises climate change and rapid urbanisation as the key drivers of disaster risk, notably the heightened risks of a rise in the sea level and more frequent and severe typhoons.

The Sendai framework emphasises taking a risk-informed approach to development and infrastructure planning – and artificial islands require development and infrastructure planning on a mega scale. Assessing disaster risk means identifying hazards and their probability, the exposure of lives and assets to the hazards, and the various systems’ vulnerability or capacity to cope with the hazards.

Unfortunately, in the rush for urban development, disaster risk reduction often takes a back seat.

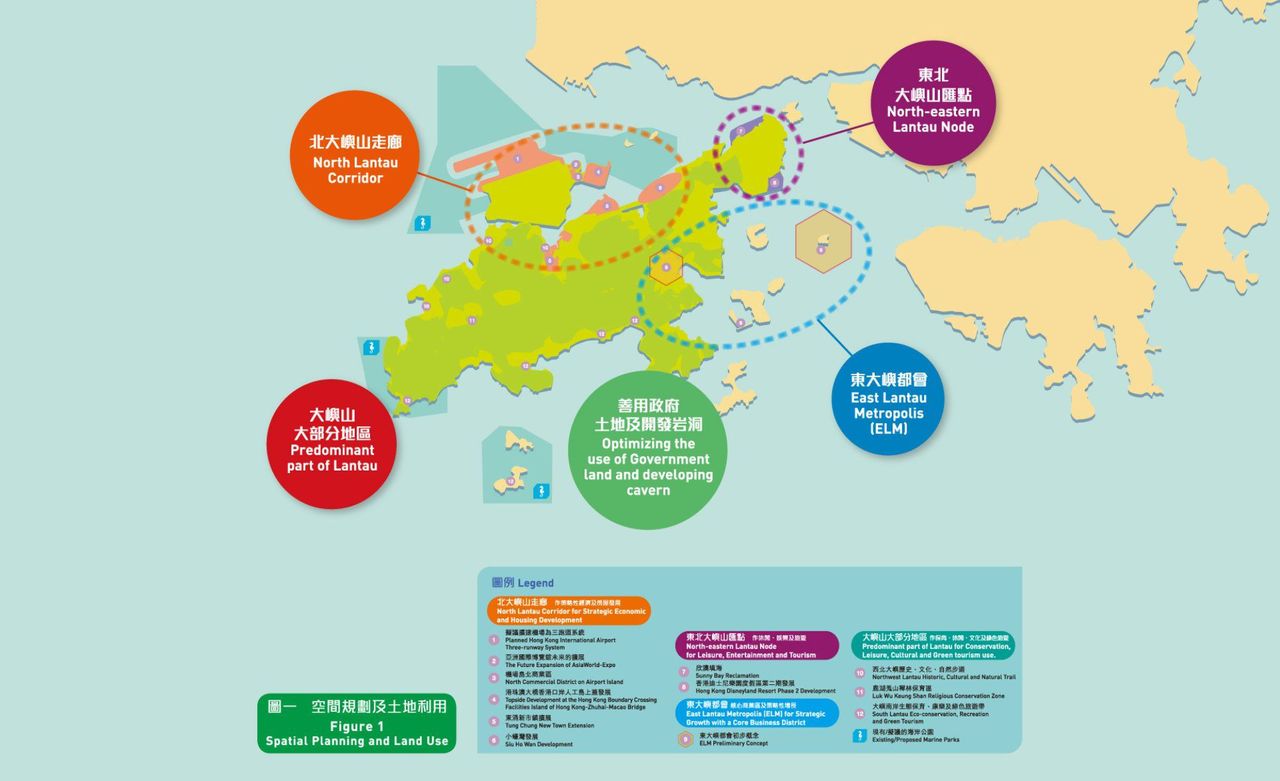

Some of the government’s proposals for “developing” Lantau.

Some of the government’s proposals for “developing” Lantau.

Building artificial islands in this era of climate change is a perfect example of creating new disaster risks – exposing human lives and properties to the growing hazards of rising sea levels and typhoons due to climate change (the Kau Yi Chau project envisions up to 700,000 inhabitants and 200,000 jobs), while reducing the capacity to cope as financial resources are drained from the building of mega artificial islands.

The financial resources allocated for the development of artificial islands could be better used in reducing disaster risks and building resilience.

Moreover, building artificial islands requires large amounts of energy and materials, particularly the huge volume of seabed sand to be extracted and transported. This will result in significant greenhouse gas emissions, at a time when the Hong Kong government has made commitments under the Paris climate accords and to carbon reduction through its Climate Action Plan 2050.

It’s also worth noting that China’s central government has also made a strong commitment to disaster risk reduction in its adoption of the Sendai framework, and in its political and financial support for related initiatives such as the Integrated Research on Disaster Risk (IRDR) programme under the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction and International Science Council; in fact, the IRDR’s International Programme Office is in Beijing.

Five years ago, the Kansai airport in Osaka that was built on an artificial island flooded after Super Typhoon Jebi hit Japan. That same month, Hong Kong was struck by Super Typhoon Mangkhut, leaving tens of thousands of households losing water and electricity, over 600 road sections closed and railway services severely disrupted.

Both Osaka and Hong Kong are on a list of cities facing threats from hurricanes and storm surges related to climate change, in a study by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) published in 2008. Out of the 136 port cities studied, each with a population of more than 1 million, the OECD ranked Hong Kong 12th in terms of its exposure to the threat of hurricanes, with Osaka-Kobe ranked 6th.

In terms of exposure to the threat of storm surges on property, the report estimated that by 2070, Hong Kong’s ranking would rise from 20th in 2005 to 9th, while Osaka-Kobe would fall from 4th to 13th.

But its assessment of Hong Kong’s risks had not even taken into account the threat to the proposed artificial islands of the East Lantau Metropolis.

Tuvalu, an island state in the far southwest Pacific, made the world sit up in 2001 when its government announced evacuation plans in the face of rising sea levels. It’s home to just 11,000 people; 22 years on, residents remain on the island, facing a sinking future.

If Hong Kong needed to evacuate the hundreds of thousands it envisioned living on the reclaimed East Lantau Metropolis, how much more difficult would that be?

With the city looking for a fresh start after the Covid-19 pandemic, we hope that Hong Kong will continue to reduce its disaster risks rather than create new ones for itself, and that it remains a safe home that can retain its people and attract talent. We believe that a good narrative of Hong Kong must be grounded in sound science and rationality.

China has unveiled an ambition for high-quality development throughout the country; this surely also means a development path that is risk-resilient and sustainable. Being at the global forefront of climate change and disaster risk reduction actions would contribute to a good narrative for China too.