Hong Kong News

Hong Kong needs its own Anthony Fauci to beat politics-driven vaccine fear

With Hong Kong aflutter in the Omicron crosshairs and pressure from the mainland to emulate its “dynamic zero-Covid” approach, the city is split once again along well-entrenched fault lines.

Pundits argue that staying in lockstep with Beijing is necessary to reopen the border for quarantine-free travel and economic exchange. Not everyone agrees, but with medical frontiers heading into uncharted Covid-19 territory, they could be right.

Maria van Kerkhove, the World Health Organization’s technical lead for Covid-19 response, recently said Omicron would not be the final variant “because this virus is circulating at a very intense level around the world”.

This should give anyone pause as Omicron continues its rampage through a global laboratory of the unvaccinated and susceptible. As China revels in the spotlight of a bubble-wrapped Winter Olympics, it has firmed its resolve to stamp out Covid-19 and prove the sagacity of its unique course.

Yet, tightening restrictions has had unintended consequences in Hong Kong. Divisions have deepened. Debate has retreated underground where it is harder to feel the pulse, offering the government fewer tools to track true infection levels or communicate effectively.

It is clear that many fear quarantine more than Covid-19 itself, which has presented in a comparatively milder form with Omicron. Why go to a doctor with a runny nose if there’s a chance you and your family could get locked up for a few weeks?

Covid-19 vaccines have provoked sullen resistance and spawned all manner of remarkable theories. This is unfortunate as many, understandably tired with the long wait for normality, are tossing the baby out with the bath water.

This dogged polarisation of society could be seen as a relic of the street protests that were quashed by a sweeping national security law. However, it would be dangerous to write off these fears without a full understanding of their cause.

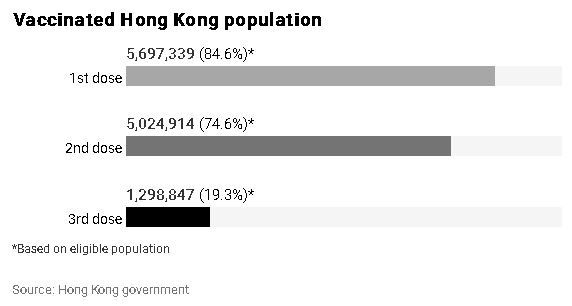

The statistics are revealing. Just 74 per cent of Hongkongers aged 12 and up are fully vaccinated with two doses a full year after vaccinations began, with a large number still unconvinced. Compare this with Singapore, where 88 per cent of the population is fully vaccinated with two doses, and China with 85 per cent.

Several African countries are well below the safe threshold. Cameroon had about 2.5 per cent of its population fully vaccinated by early February, Kenya 12.3 per cent and Egypt 27 per cent. The United States is still struggling at 64 per cent.

The prime challenge before the Hong Kong government is not vaccination enforcement, having mandated strict new rules for access to shopping centres, restaurants, supermarkets and so on. Instead, it is the continued lack of public trust and a growing sense of fear.

The city’s overcentralised, top-down system of governance has simply not allowed for the emergence of a credible, apolitical voice – a figure like America’s top infectious disease expert Anthony Fauci, who could deliver the facts without having science rubbished by those distrustful of the government and its motives.

Having the chief executive of the city as the leading voice on pandemic control has risked needlessly politicising a community health issue. The political tone must be lowered and, if possible, eliminated.

Offering the pulpit to a respected person of science is one way to defuse tension. Some might argue it is too late for that, but better preparedness for future crises that will inevitably emerge is vital.

Hong Kong has its well-regarded Centre for Health Protection, which has a role similar to the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Yet its controller Dr Ronald Lam Man-kin, who is also director of health, is not sufficiently visible when it comes to public persuasion. He could team up with leading virologists and scientists to offer regular, data-rich briefings with punch and credibility, thus separating medicine from rumours.

In 2003, the man of the hour was Malik Peiris, a Sri Lankan virologist who made his home in Hong Kong and led the fight against Sars. His lab was the first to successfully isolate that virus, and he has been at the forefront of research on zoonotic viruses, making him uniquely positioned to explain a coronavirus like Sars-Cov-2.

Discourse must be brought above ground and fears addressed. The government simply does not have the resources to manage lockdowns and quarantines of large housing estates across the city.

This requires vast numbers of trained staff for security, faster testing, medical intervention, compassionate counselling, elder care, food supply and so on. It raises issues of mental well-being, livelihood and a diminution in human capital at a time when the economic engine is sputtering.

Lockdowns on an industrial scale will not work the same way as on the mainland. Domestic demand and supply there are enough to keep the cogs whirring for a while in an autarkic bubble.

The Hong Kong mindset is different. The city also has an open-door, laissez-faire economy that is heavily dependent on imports – 90 per cent of the city’s food is imported. It is almost wholly premised on abstract notions of free will.

Straitjacketing this population risks pushing more discourse and grumbles underground, leaving the administration struggling to steer an unwieldy iceberg with too many unknowns lurking below the surface. It might be wise to steer a middle course – speedier, more accessible testing and short-duration stay-at-home requirements with better support for those who have contracted the virus.

This needs to be combined with a massive, well-coordinated communications roll-out spearheaded by medical professionals and enlisting the support of the remaining political opposition to help sway reluctant constituents.

This is a matter of health and public safety, not politics. The quicker all those eligible are vaccinated, the sooner the city can reopen.