Hong Kong News

Hong Kong leader defends history teaching policy amid massacre video saga

Hong Kong’s leader has defended her government’s approach of leaving schools to exercise professional judgment when teaching dark chapters of history, after some pupils were left distraught by graphic footage of the Nanking massacre.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor stressed the importance of learning about China’s past, but said teachers were best placed to ensure lessons were age appropriate as she noted past complaints of officials trying to “control everything”.

“It’s not for education officials to dictate or ... provide very detailed guidelines on what to show, when to show and so on,” she told her weekly press briefing on Tuesday.

The controversy emerged after PLK HKTA Yuen Yuen Primary School in Tuen Mun showed footage to pupils – some reportedly as young as seven – of the invading Imperial Japanese Army’s brutal massacre of Chinese civilians in the city now known as Nanjing.

The Education Bureau provided the videos to schools as part of commemorations marking the 84th anniversary of the massacre, which was launched on December 13, 1937.

Some pupils, including those in Primary Two, were described as being distraught by the documentary’s scenes of rampaging Japanese soldiers burying people alive and shooting them in the head.

Lam said she hoped the public would recognise that learning Chinese history was “absolutely important for school education”.

“If we don’t understand history, it’s hard to understand the significance and uniqueness of ‘one country, two systems’,” she said, referring to the governing principle for Hong Kong.

“[But] while learning history is of paramount importance, how to learn is something we would defer to the education sector, because we have very well-trained teachers, [and] we have well-run schools.”

PLK HKTA Yuen Yuen Primary School in Tuen Mun is at the centre of the latest education saga to befall Hong Kong.

PLK HKTA Yuen Yuen Primary School in Tuen Mun is at the centre of the latest education saga to befall Hong Kong.

Asked if the bureau could have issued more detailed guidelines on how the subject should be taught, Lam referred to previous criticism of the bureau for apparently trying “to control everything”.

Lam added that rather than micromanage the curriculum, the role of education authorities was to remind schools of the kind of Chinese history teaching materials publicly available.

“That video which has caused some anxiety is available in the public domain … but I believe that the Education Bureau has not mandated that all teaching on this Nanking massacre has to show that video, so this is a matter of professional judgment by the teachers,” she said.

Lam said she believed that schools and educators could learn a lesson from the saga. Teachers should ensure they used the right materials, such as photos and videos, when teaching history so they did not cause anxiety, she added.

Separately on Tuesday, Vu Im-fan, a principal who is also chairwoman of the Subsidised Primary Schools Council, said teachers only received the lesson materials and a circular informing schools of the requirement to commemorate the Nanking massacre at the end of November. That meant the time available to schools for planning the relevant activities was quite rushed, she added.

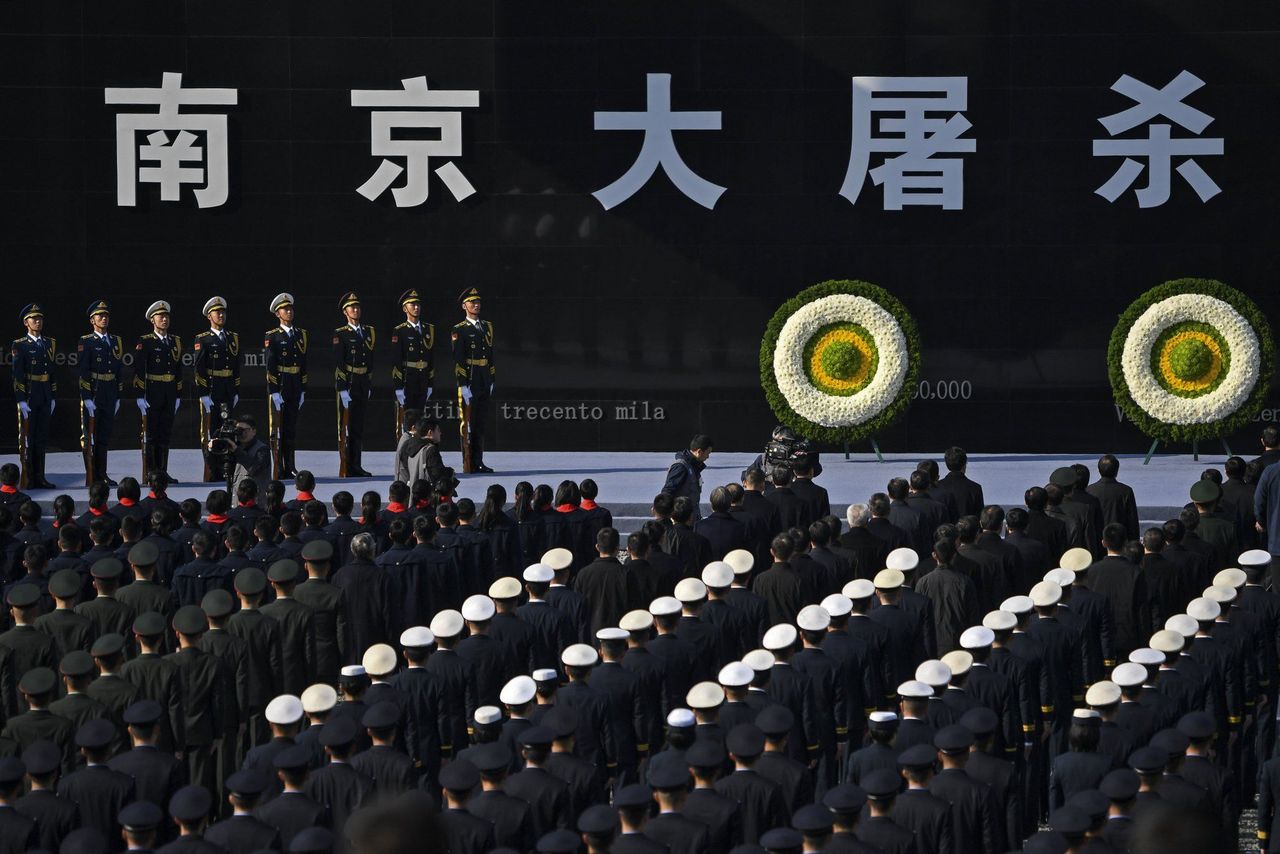

A memorial ceremony for the Nanking massacre victims was held on Monday on the 84th anniversary of the atrocities.

A memorial ceremony for the Nanking massacre victims was held on Monday on the 84th anniversary of the atrocities.

Vu stressed, however, that teachers generally possessed the necessary professional judgment to decide how to use the official materials, based on a school’s context and the needs of its students. She accepted that the bureau had given room for schools to deliver the lessons as they saw fit.

“Schools have responsibilities to review the materials before passing to students and it will of course be ideal for the bureau to issue clear guidelines on which levels of students should use the materials in the future,” said Vu, the principal of Kowloon Bay St John The Baptist Catholic Primary School.

Vu said that talking to other principals revealed that many of them and their staff had also felt unwell after watching the videos.

“Some schools, like us, decided not to play the videos to students. We just used pictures to explain what happened,” she said.