Hong Kong News

Hong Kong exporters risk missing Christmas peak amid supply chain crisis

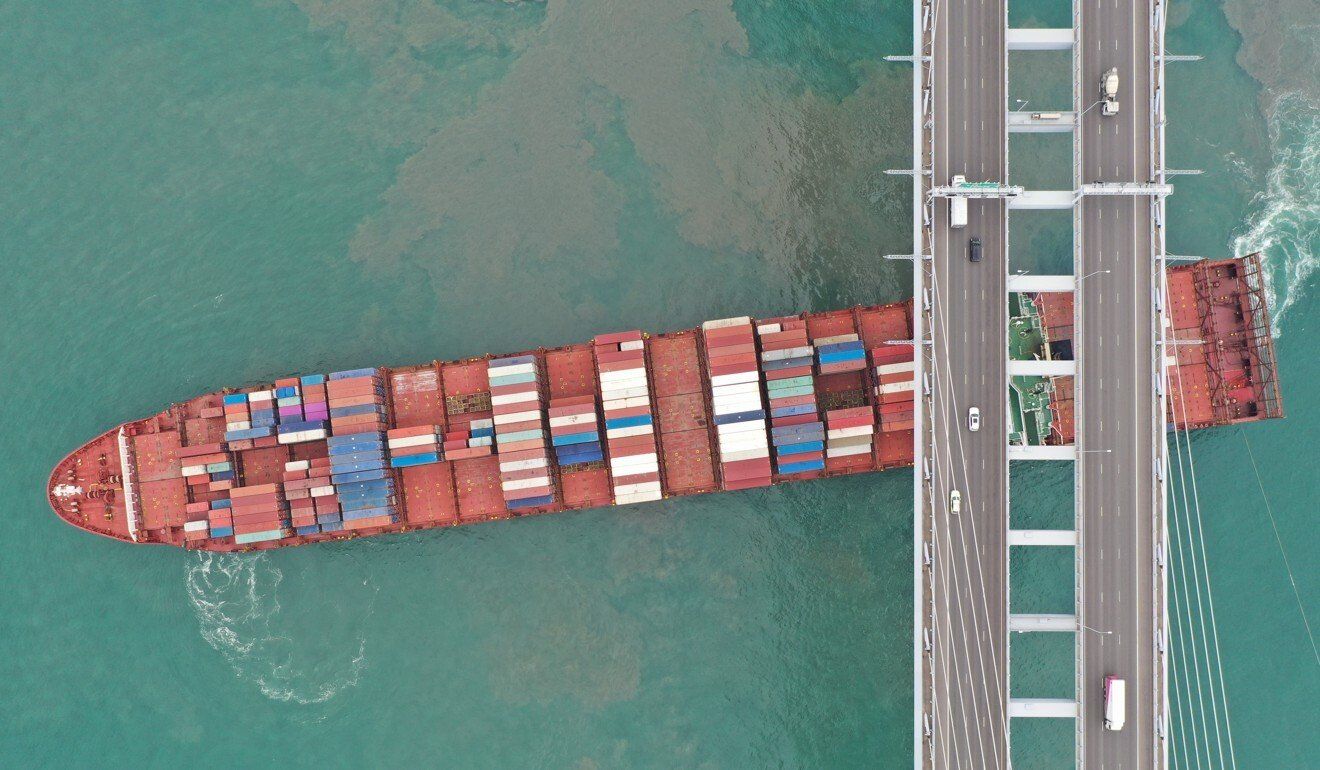

Many Hong Kong exporters are facing severe cash flow problems ahead of the peak Christmas season, with the global supply chain crisis leaving their deliveries stranded at ports in the United States and their goods at factories in mainland China.

Hong Kong Shippers’ Council chairman Willy Lin Sun-mo said there were too few containers to meet demand, resulting in many cases of undelivered goods and delayed payments.

“If you can’t get a container by now and the goods are seasonal, there is a high chance you will miss the Christmas shopping season,” he said.

Some exporters have resorted to sending their goods by air, which can cost 10 times more than transporting a 40-foot container by sea.

“Normally goods for Christmas would have shipped by September, but the global supply chain crisis has, at best, left them piled up at the ports of the US west coast or, at worst, remaining at mainland factories,” Lin said.

The global supply chain has broken down as a result of pandemic-related lockdowns, and a lack of crew, containers and capacity at US ports.

Ironically, the economic rebound that followed the easing of pandemic restrictions has made matters worse.

Lin said it now took 180 days – nearly three times longer than before the pandemic – for a container ship to get from Asia to the US’ west coast and back.

“Delays in shipments will cause delays in payments for several months,” he said. “How can small and medium-sized enterprises [SMEs] survive?”

The economic rebound that accompanied the easing of pandemic-related restrictions has exacerbated supply chain problems.

The economic rebound that accompanied the easing of pandemic-related restrictions has exacerbated supply chain problems.

Steve Chuang, founder and CEO of the electronics firm ProVista Group, said he had to wait for up to a month to confirm a booking for a 40-foot container, whereas he used to get instant confirmation before the pandemic.

“At one point, I had 60 40-foot containers of electronic products stuck in mainland China and had to rent a huge storage area for them, while facing the risk of my orders being cancelled,” he said.

He sent some higher-value products, such as solar power storage systems, on chartered flights to the US, but that cost at least 10 times more than the US$25,000 (HK$194,300) he typically paid for a 40-foot container.

Shipping expenses used to account for less than 5 per cent of his company’s total costs, but now made up 20 per cent, he added.

He said many exporters now had to bargain with their clients overseas to reach a compromise over the higher delivery costs.

Hong Kong General Chamber of Small and Medium Business president Joe Chau Kwok-ming, whose family owns a baby clothing company, heard from clients in the US that shipment delays had prompted some smaller department stores to cancel orders.

To help SMEs and individuals, the Hong Kong government last month extended three borrowing schemes by six months. The Special 100% Loan Guarantee, the SME Financing Guarantee Scheme and the Preapproved Principal Payment Holiday Scheme have so far doled out a total of HK$170 billion (US$21.9 billion).

“I call on banks not to recall any loans at this critical time, to throw a lifeline to SMEs,” Chau said.

He said whether retailers would have enough products on their shelves for Halloween, Thanksgiving and Christmas would depend on whether importers could pay for more expensive shipping.

Supply chain issues have forced some exports to resort to air freight, which can cost 10 times as much as shipping by sea.

Supply chain issues have forced some exports to resort to air freight, which can cost 10 times as much as shipping by sea.

Steve Lamar, Washington-based president and CEO of the American Apparel and Footwear Association – which represents more than 1,000 major brands – told the Post he saw no end to the supply chain crisis.

He said even though California’s Los Angeles and Long Beach ports, the busiest two in the US, began working round the clock earlier this month, it was only a symbolic move and American authorities had to do more.

His group has called on US President Joe Biden’s administration to suspend tariffs and refund some of the US$110 billion taxes paid by American companies to help them survive the supply chain crisis.

Lamar said US companies and consumers were suffering too.

“Runaway freight costs, cargo delays and crushing tariff burdens are now fuelling an inflationary spiral,” he said.