Hong Kong News

Hong Kong doesn’t need teachers against national education: John Lee

Hong Kong does not need teachers who refuse to dedicate themselves to national education, Chief Executive John Lee Ka-chiu has said, though he stressed such individuals were in the minority in the sector.

The city’s new leader was asked in a televised interview on Saturday how he intended to deal with the trend of teachers quitting over disagreements with what should be taught.

“If they don’t match our requirements, I don’t want their teaching to deviate from our mainstream ideology,” Lee said, vowing to provide “multifaceted” national education in schools.

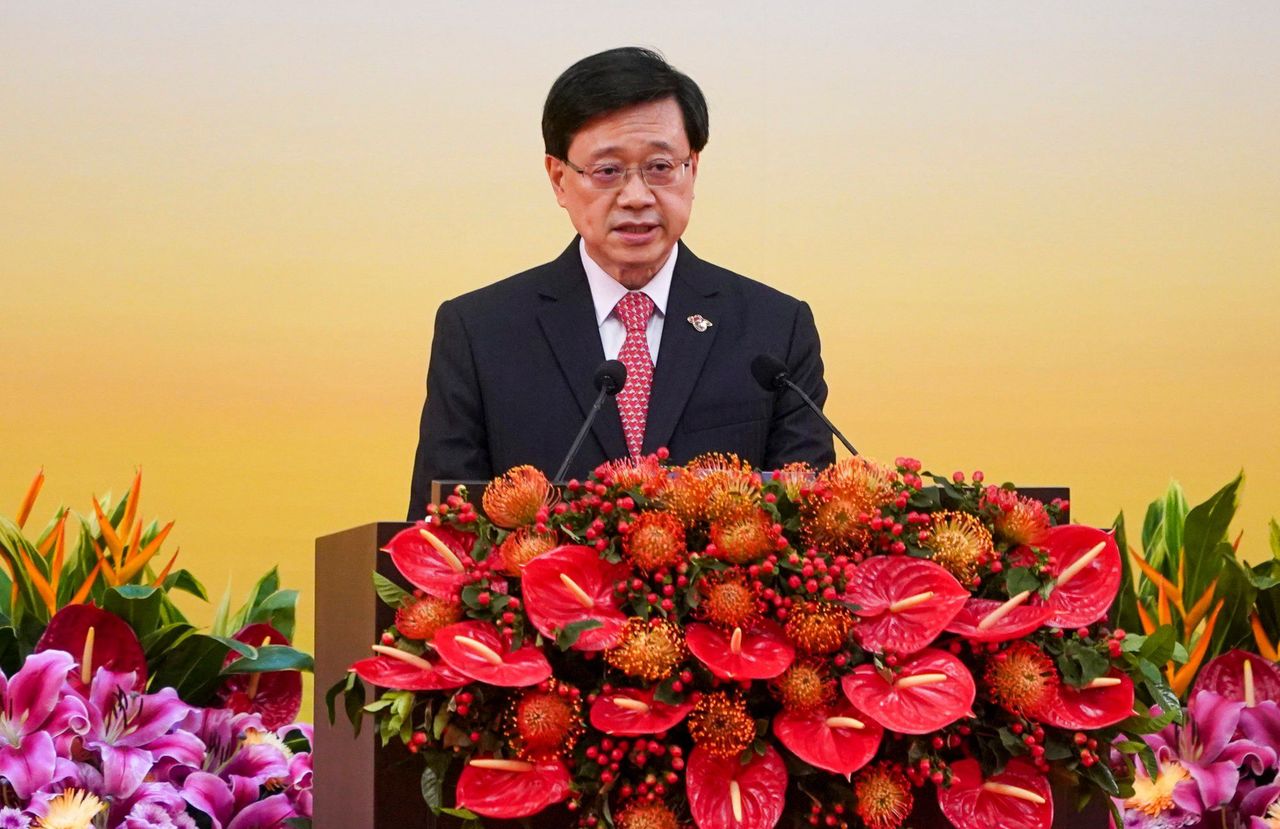

Hong Kong’s Chief Executive John Lee.

Hong Kong’s Chief Executive John Lee.

He said his remarks were centred on Chinese President Xi Jinping’s call during a recent visit for Hong Kong to promote Chinese culture and the sentiment of “loving the country, loving Hong Kong”, a mantra cited often by officials and the pro-establishment camp.

But Lee added: “I am also confident that mainstream teachers are very professional and very serious about pushing forward education on this aspect.”

He said national education should not be a stand-alone subject, but one infused into students’ everyday lives so they could learn about the “substance, goal and target” of the matter.

Schools currently had Chinese history as a compulsory subject for lower forms, Lee noted, while teachers would be provided with relevant training, and students would have the opportunity to go on exchange trips to mainland China.

He attributed the 2019 anti-government protests, which many young people had joined, to improper national education, leading the city in the wrong direction, adding that “we have to right the wrong”.

In late May, the Hong Kong Association of the Heads of Secondary Schools released a survey, which it said bore signs of a “ferocious departure tide”.

Each school lost an average of 7.1 teachers in 2020-21, with the figure standing at 3.9 in 2019-20 and 4.2 in 2018-19, according to the association.

Lee also gave more details on his new Chief Executive’s Policy Unit, revealed on Wednesday when he attended his first Legislative Council question and answer session.

The policy unit, aimed at gauging public sentiment and helping the chief executive to get a better grasp of national development as well as international situations, was revamped from his predecessor Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor’s Policy Innovation and Coordination Office, previously the Central Policy Unit.

Asked whether he would include people from the opposition camp, Lee said he would not rule out the suggestion, though he also stopped short of an affirmative answer.

“I will look at what the person can help with and what they can contribute,” he said.

Towards the end of her term in June, Lam decided not to determine whether she would raise civil servants’ salaries.

An earlier proposed adjustment to civil servants’ wages, based on a sector survey of data collected from 111 private companies, had courted controversy with the report’s suggestion that those in the senior salary bands get rises of more than 7 per cent.

Lee and his advisers endorsed an across-the-board pay rise of 2.5 per cent earlier this week instead.

Asked if he felt Lam left him a “bomb” to defuse at the start of his term, Lee said he did not agree with the narrative.

“It’s not something I have to consider … When problems arrive I just have to deal with it positively,” he said, adding that the decision already took into account civil servants’ morale as well as the city’s battered economy.