Hong Kong News

Hong Kong courts should keep Basic Law out of political games

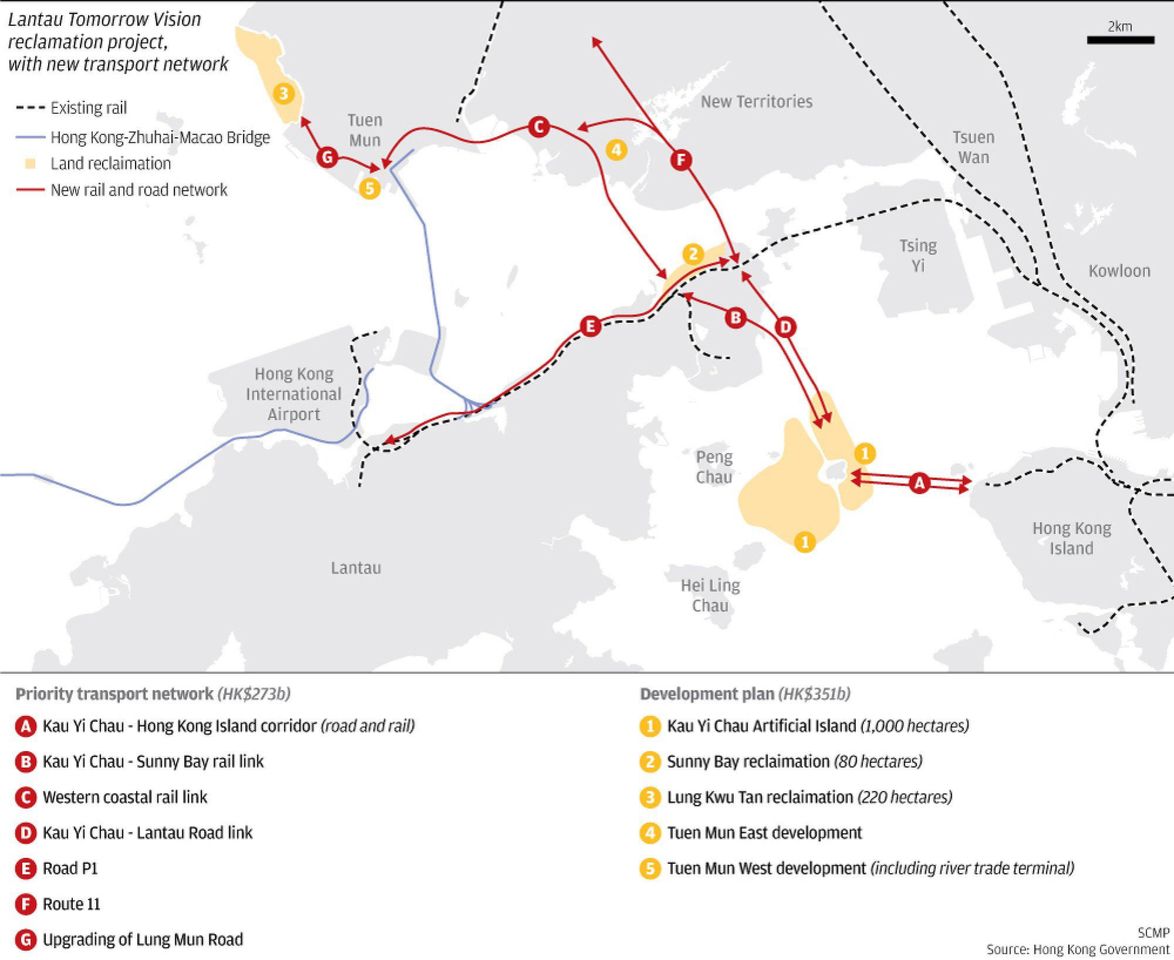

To redress the situation of Hong Kong’s acute home shortage, the government has an ambitious plan : to reclaim at least 1,000 hectares of land east of Lantau for housing. The first step was to commission a feasibility study and, for this purpose, the government put before the Legislative Council a request for HK$550 million. This was approved on December 4, 2020.

On July 27 this year, Kwok Cheuk-kin took out a Form 86 under the Rules of the High Court, to apply for leave to start proceedings for a judicial review, naming Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor as the proposed respondent. The premise was that she made a funding request that was said to be against the principle of “keeping expenditure within the limits of revenue” under Article 107 of the Basic Law.

The application was considered by High Court Justice Russell Coleman on August 12 and, in a six-page determination, it was dismissed.

Although the applicant had sought to impeach Lam for her act of making the funding request on December 4, the Legislative Council in fact approved the request that same day. Yet the application for judicial review was not made until nearly eight months later. The proceedings were futile, and totally without merit.

Kwok Cheuk-kin appears at the High Court in Admiralty in October 2018.

The retired civil servant has been filing applications with the High

Court since 2006, often challenging the legality of government policies.

Kwok Cheuk-kin appears at the High Court in Admiralty in October 2018.

The retired civil servant has been filing applications with the High

Court since 2006, often challenging the legality of government policies.

The judge said Kwok was “well known as a frequent applicant”, as indeed he was. He had, over the past decade, made scores of applications, supported by legal aid, to the extent that he was dubbed the “king of judicial reviews” by the media.

One should be amazed at the court time wasted in entertaining Kwok’s futile applications and the money paid by the Legal Aid Department to support those applications.

Judicial reviews are governed by strict rules. They concern acts of executive authorities which are unlawful or in excess of statutory powers. Where the court grants relief, it has serious consequences for the whole community, not simply for the applicant. Judicial review is not a portal for a personal gripe by an individual against the government.

It should have been obvious to the judge at first glance that Kwok’s application was futile, frivolous and vexatious. And it was well out of time.

It should have been dismissed out of hand. But, instead, the judge chewed over the provisions of Order 53 rule 4(1) of the Rules of the High Court, which limit the time for a judicial review application to within three months, and considered the court’s discretion to extend time. What for?

The judge also pondered over whether the chief executive had made any “decision” that could be the subject of a judicial review.

He then considered whether it was arguable that Article 107 of the Basic Law had been breached: a provision which simply says that the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region should keep expenditure within the limits of revenue. The judge said the HK$550 million was, arithmetically, less than 0.0008 per cent of the total government budget for 2020-21.

He said: “If the underlying concern is simply one as to whether Article 107 has been respected, I do not think it reasonably arguable that is the concern raised by these proceedings as framed.” Does it mean that, differently framed, he might have given leave for an argument based on a breach of Article 107 to proceed?

The judge seems blind to the wider implications of an attack based on Article 107.

The Basic Law is the constitutional framework for the Hong Kong SAR as a whole, promulgated by the National People’s Congress. It is not a civil code for Hong Kong’s governance: that is left to the common law, the statutes and subsidiary legislation.

Did Kwok’s application raise an issue where the chief executive could be said to have broken Hong Kong law, or exceeded her powers? Clearly not. How then could it be remotely arguable that, in submitting to the Legco a funding proposal, the chief executive’s action could be impeached by a judge on constitutional grounds?

Where a case concerns the everyday running of the government, it should be extremely rare that articles in the Basic Law are engaged. For the issue is then no longer one of regional law; it becomes a matter of national law.

And it concerns, ultimately, Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy. The final power of interpretation of the Basic Law lies, not with the Hong Kong courts, but with Beijing. Hence, every time a court holds that a provision of the Basic Law is engaged in the protection of some private right, the court puts, in effect, a dent in Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy.

And yet the law reports are crammed full of cases where the courts have struck down acts of the executive for violation of the Basic Law, or given ponderous consideration to arguments to that effect. Lawyers have been allowed – and indeed encouraged – to play games with the Basic Law.

It is this laxity in process, this permissiveness, that encourages people like Kwok to make repeated futile applications to court. If he is a “serial applicant”, the courts have made him so. This is the product of the ingrained culture of the judiciary, and Justice Coleman, in his determination, was simply following that established trend.

Kwok’s concern, he noted, was “in reality a political, economic or socio-economic grievance” and that “asking the courts to address what are really non-legal questions” would “potentially divert judicial resources from being more appropriately and timeously deployed”. Why, then, spend so much time and energy in dealing with Kwok’s application?

It is high time for the judiciary to take a hard look at its own culture, asking whether the current processes need tightening to be made more robust and effective.

And there is also the wider question: whether its approach to such cases amounts to the full and vigorous implementation of the “one country, two systems” principle, particularly where the Basic Law is involved.

Beijing recently announced the “Outline for the Implementation of a Law-Based Government (2021-2025)” programme to help China become a rule-of-law country by 2035.

In developing this process, is Hong Kong’s system a model to be followed? And what does it say about the long continuation of the common law in Hong Kong, beyond 2047, if the answer is “no”?