Hong Kong News

Hong Kong Bar chief Paul Harris ‘pulled’ from national security trial

Hong Kong’s Legal Aid Department removed Bar Association chairman Paul Harris, a prominent human rights lawyer called an “anti-China politician” by Beijing, from a national security trial months ago against his activist client’s wish, the Post has learned.

The senior counsel’s removal came even before the department’s recent announcement that it intended to scale back a series of discretionary options, including withdrawing from defendants’ the chance to pick their own lawyers. Critics have warned the changes could harm activists and opposition figures’ access to justice.

Legal insiders on Tuesday said the changes were already under way, affecting a number of activists facing the most serious national security charges, despite only being floated in October.

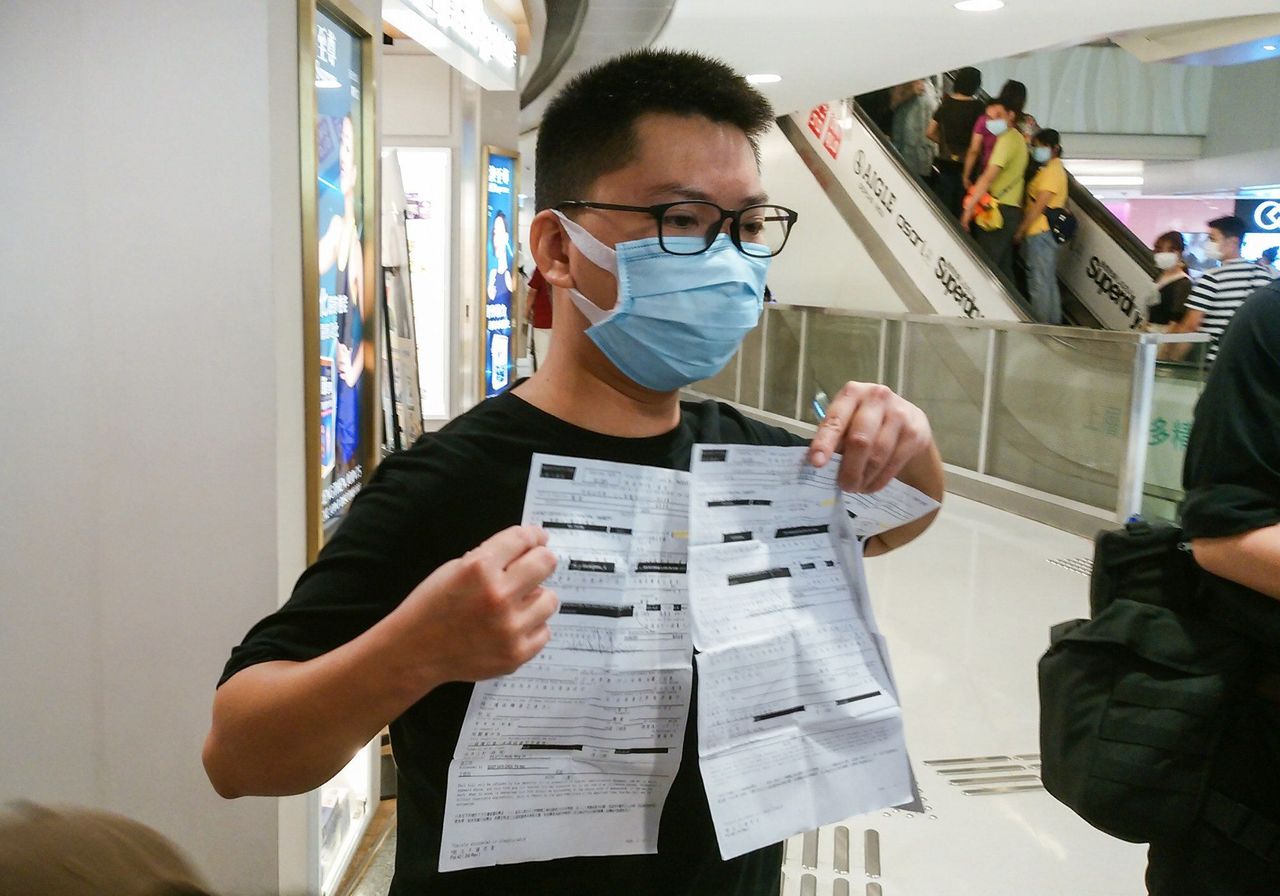

Adam Ma.

Adam Ma.

Among those affected are some of the 47 opposition figures charged with subversion for their part in an unofficial election primary last year, which prosecutors allege amounted to a wider plot to paralyse and overthrow the government.

Sources said Harris was pulled from activist Adam Ma Chun-man’s legal team weeks before he faced trial at the District Court on charges of inciting secession in September, ahead of the introduction of the legal aid reforms.

Ma, the second person convicted under the Beijing-imposed national security law, had his case handed to another senior barrister before trial. The activist, best known by his moniker “second-generation Captain America” due to his protest costume, was jailed in November for five years and nine months.

Two sources said that before the trial, department staff visited Ma in August at the maximum-security Stanley Prison, where he was being detained, and warned him against hiring Harris.

By then, Harris had twice helped Ma apply for bail after he began representing him last November, when the activist was charged.

Former opposition lawmakers and activists are accused of subversion over an unofficial election primary.

Former opposition lawmakers and activists are accused of subversion over an unofficial election primary.

Harris has been in Beijing’s crosshairs since taking the helm of the Bar Association in January, when he vowed to advocate changes to parts of the national security law imposed the previous June. His since-rescinded membership of Britain’s Liberal Democrats party also proved problematic for Beijing.

At the August meeting, the sources said, the department staff allegedly told Ma he had to ditch Harris because appeal judges had criticised the barrister in a separate judicial review case concerning an anti-government protester with an injured eye trying to stop police accessing her medical records.

That case had drawn the ire of the pro-establishment camp, which accused Harris of taking it on to help the female protester block police. The woman’s medical records were key to discovering whether her claim that she was injured by a police projectile during a 2019 protest was true.

Several pro-establishment lawmakers also cited the case on numerous occasions when they demanded the department implement reforms to prevent what they believed to be a small group of pro-protester lawyers taking on all such cases.

The department eventually assigned Edwin Choy Wai-bond SC to Ma following the prison visit. And despite the 31-year-old activist’s subsequent request to retain Harris, he was told in a letter his demand could not be acceded to. No further reasons were given in the department’s letter.

Ma refused a Post request for an interview. His legal team and Harris also declined to comment.

But a separate legal source said the removal of Harris was likely to have been one-off and could be related to Ma’s wish at one point to have his trial conducted in Chinese.

A spokesman for the department said it would not comment on individual cases.

However, he stressed: “We will take into account various factors such as the experience and expertise of the individual lawyer, the nature and complexity involved in the case, the language used in the trial etc, in deciding whether a particular lawyer is suitable based on the existing assignment criteria.”

Asked if Harris had been removed from its list of lawyers entirely, the spokesman replied: “No, Mr Harris has not been banned from taking up legal aid cases.”

One lawyer, who preferred to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of the matter, said he could already see problems in the way Ma’s legal aid application, and subsequently his case, was handled, even before the department implemented changes.

Barrister Edwin Choy.

Barrister Edwin Choy.

While acknowledging Choy’s experience in the criminal law field, he said Ma’s case centred on allegations he chanted separatist slogans and advocated independence through press interviews, meaning his trial would be filled with constitutional issues.

“Paul Harris’ arguments could have been based on human rights and constitutional law. Also, he had been following the case all along,” he said.

Under the department’s latest proposals, defendants receiving legal aid will no longer be able to choose their criminal lawyers, while barristers will be subject to a yearly quota of no more than three judicial review cases, a form of legal means available to the public to challenge the government. Meanwhile, solicitors will be capped at five cases per year.

In another development, it was revealed during a court hearing last week that Leon Tong Ying-kit – the first person charged and convicted under the national security law – would no longer be represented by Bond Ng Solicitors, a law firm known for handling activists’ cases, in his appeal in March next year.

The case has been assigned to W.K. To and Co, which has a broader practice including corporate law and a wider range of clients such as state-owned enterprises in mainland China. Tong, who drove his motorcycle into a group of police officers during a protest, was convicted of terrorism and incitement to commit secession.

Legal sources also said some defendants among the 47 opposition figures had already been told they would not be assigned the lawyers they requested, or that they would have to pay deposits, for sums of as much as millions of dollars, before they would find out.

Some are contemplating raising funds to hire private lawyers, they said.

“Some can’t even be bothered trying to apply for legal aid,” one lawyer involved in the case said.

US-based legal scholar Michael Davis, from the Woodrow Wilson International Centre, said he feared it was the authorities’ attempt to sideline human rights lawyers.

“Since these lawyers are the most experienced it cannot be good for the defendants or for the vigorous protection of human rights,” the former University of Hong Kong academic said.

Senior counsel Ronny Tong Ka-wah, who is also a government adviser, said it was common for defendants who did not qualify for full legal aid to pay a deposit.

“If all 47 are looking for the same small pool of lawyers, legal aid has its reasons to do what it did,” he added.