Hong Kong News

Hong Kong advocacy group calls for more psychiatric support for homeless residents

An advocacy group has urged Hong Kong authorities to assign more psychiatric doctors and nurses to outreach teams after its latest study found homeless people were struggling to get treatment in a timely manner.

Nurses also struggled to follow up on patients’ mental health conditions because they lacked a residential address or permanent phone number, the Society for Community Organisation (SoCO) said on Sunday.

The report released by the group featured interviews with 13 homeless people who were receiving psychiatric treatment at hospitals and observed 16 other street sleepers suspected of having such conditions.

Conducted between November 28, 2022, and January 31, 2023, the study found only one of the 13 who had received treatment had stayed in contact with nurses.

The patient, a 45-year-old man who asked to be referred to as Ying, said his monthly conversations with his community psychiatric nurse over the past two years had been a “great help”.

The regular sessions meant he had company, constant reminders to take care of his medical well-being and someone offering much-needed concern, he added.

“It is almost like having another member of my family,” Ying said.

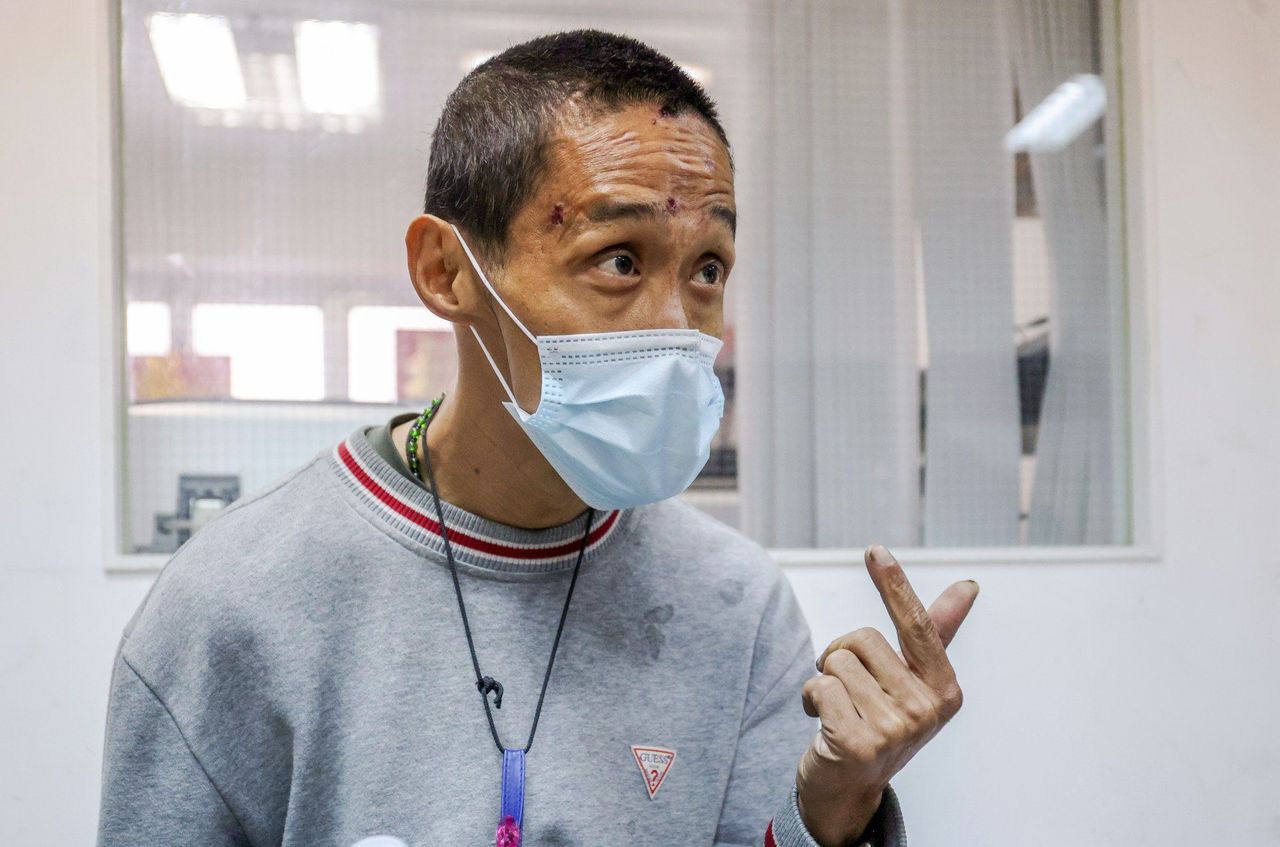

Ying, an interviewee from the study, says his monthly support sessions have been a “great help”.

Ying, an interviewee from the study, says his monthly support sessions have been a “great help”. On the difficulties of keeping in contact with medical staff, the NGO said many patients’ phones could easily be lost or run out of battery.

The group noted that some streetsleepers relied on pre-paid sim cards and constantly changed numbers since they could not afford a monthly phone plan.

One patient from the study said he originally faced a two-year waiting period for an appointment and was only sent to see a psychiatrist sooner when he was forcefully admitted to hospital for attempted self-harm.

“Being forcefully admitted to a hospital is already an extreme case because there are only two situations where this happens, either you are harming yourself or others … this is extremely undesirable,” said Ng Wai-tung, a community organiser with SoCO.

The advocacy group advised authorities to increase the promotion of local mental health resources, provide more targeted interventions for homeless people by the government’s community mental wellness centres and include psychiatrists in outreach teams.

The latter suggestion would allow psychiatrists to provide immediate assessments for potential patients, as well as interventions and service referrals, it explained.

Bakkie Chan Chung-yin, a community organiser with the NGO, also urged the government to increase the number of community psychiatric nurses and include them in the subsidised outreach teams, like the one run by SoCO, for homeless people.

Community psychiatric nurses are medical professionals who provide nursing services and treatment for patients at their residences.

Such healthcare professionals were important in helping homeless people recover from mental illnesses, but could struggle with outreach due to dealing with large caseloads and the difficult conditions suffered by such patients, Chan said.

“Because of the large number of cases, the community psychiatric nurses would close the file on [homeless patients] once they lose contact with them or could not reach them once or twice,” Chan said.