Hong Kong News

Green groups accuse government of rushing assessment of Lantau project

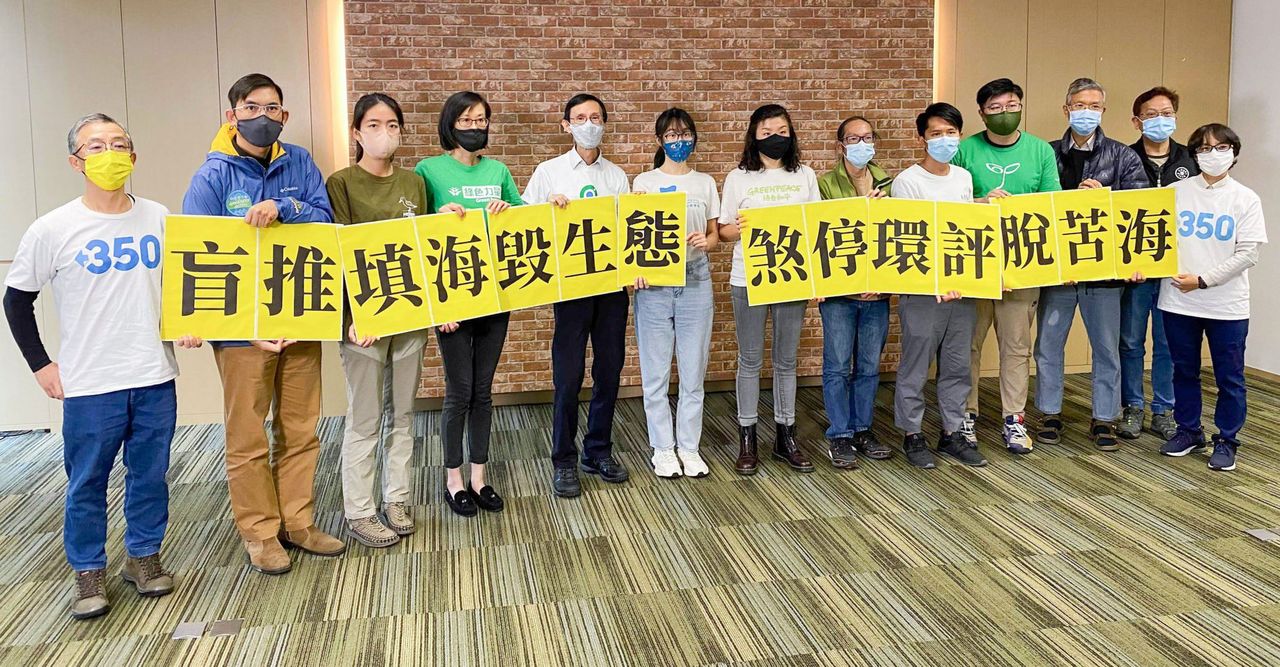

Fifteen green groups in Hong Kong have accused authorities of skipping a strategic environmental assessment of a plan to create artificial islands off Lantau Island and failing to consider alternative solutions to a shortage of land in space-starved Hong Kong.

The groups on Tuesday called on the Environmental Protection Department to “act as a gatekeeper” and reject three project profiles that they said the government had rushed through. The profiles provide details on works related to the ambitious Lantau Tomorrow Vision land-reclamation plan.

The profiles cover three major projects linked to the vision: the Northeast Lantau Link road system, the developments that would be constructed on the new islands, and the land reclamation itself.

Approving the three profiles could downplay the potential environmental impact of the Lantau Tomorrow Vision as a whole, the green groups argued.

Fifteen green groups have urged the government to reject three project profiles relating to the Lantau Tomorrow Vision.

Fifteen green groups have urged the government to reject three project profiles relating to the Lantau Tomorrow Vision.

The project, unveiled in 2018, calls for the construction of 1,700 hectares of man-made islands that would support a housing and business hub. It also involves a transport network linking the islands to Lantau, Tuen Mun and Hong Kong Island.

“For such a large-scale reclamation project, we believe the government should do the utmost and thoroughly go through all the steps,” said Edwin Lau Che-feng, founder and executive director of The Green Earth.

Under a strategic environmental assessment, departments steering major public projects and policies are required to look at other development alternatives and compare the environmental impacts of all options. It encourages the administration to make decisions to address the cumulative impact instead of the effects of individual projects.

The two-week public consultation on the three project profiles will end on Thursday.

The first phase of the Lantau Tomorrow Vision involves reclaiming 1,000 hectares of land near Kau Yi Chau Island, which will provide between 150,000 and 260,000 flats and accommodate 400,000 to 700,000 people.

Lau, a former member of the Advisory Council on the Environment, said the government should first complete the Lantau Tomorrow Vision’s 42-month feasibility study – which began in June this year – to determine whether it is possible to proceed with the project.

Authorities should carry out a strategic environmental assessment to examine other land supply alternatives, such as the development of brownfield sites, and study the environmental impact of each option.

Before the feasibility study is released or the review of other options is done, the government should not jump to the environmental impact assessment stage right now, Lau said.

“If they go ahead as planned, it will set a very bad precedent for any future projects,” he said.

He added that the project profiles do not address the issues of climate change and carbon emissions, which could delay Hong Kong’s target of achieving net zero emissions by 2050.

Edwin Lau Che-feng, founder and executive director of The Green Earth,

says the government ‘should do the utmost and thoroughly go through all

the steps’ required of such a massive project.

Edwin Lau Che-feng, founder and executive director of The Green Earth,

says the government ‘should do the utmost and thoroughly go through all

the steps’ required of such a massive project.

The groups also criticised the government for failing to provide information from two studies related to the Hong Kong 2030 Plus strategy, which projected the overall demand for and supply of land over the 30-year period between 2019 and 2048.

The two studies included an environmental assessment on the city’s future infrastructure development that also covered the 1,000 hectares to be reclaimed off Kau Yi Chau.

Earlier this month, members of the Advisory Council on the Environment asked for reports on the two studies, but officials would promise only to regularly report to the council on the assessment’s progress.

Hong Kong is the world’s least affordable residential property market, and Beijing has called the city’s housing shortage a “deep-seated problem” that must be addressed.

At the end of September, about 153,700 Hong Kong families were waiting an average of 5.9 years to be allocated a public housing flat, with many forced to live in cramped conditions while they wait.

A project profile is submitted to the Environmental Protection Department when the proponent applies for a study brief to begin an impact assessment study.

After completion of the study, the project proponent will seek the department’s approval of the accompanying report, which demonstrates that the assessment meets the requirements of the Environmental Impact Assessment Ordinance – enacted in 1998 to avoid, minimise and contain the adverse effects of development on the environment.

Viena Mak Hei-man, vice-chairwoman of the Hong Kong Dolphin Conservation Society, said past environmental impact assessment reports had underestimated the impact on marine ecology and the proposed mitigation measures, including marine parks to compensate for habitat loss, were not effective.

Mak noted that Chinese white dolphin numbers in northern Lantau plummeted after construction works on the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge began in 2011, and warned of similar consequences.

Greenpeace East Asia campaigner Chan Hall-sion said it would be difficult to comprehensively assess the environmental impact of the Lantau Tomorrow Vision without adequate information.

“The [Environmental Protection Department] has the responsibility to act as a gatekeeper to ensure that development does not come at the expense of environmental protection,” she said.

The department said in a reply to the Post that the Environmental Impact Assessment Ordinance provided for an “open and transparent process”, and that any comments received would be taken into account.

The Post has also contacted the Planning Department for comment.