Hong Kong News

Free gene mutation tests offer Hong Kong lung cancer patients chance to live longer

Late-stage lung cancer patients in Hong Kong can get free gene mutation tests to identify treatments which could help them survive longer and have a better quality of life.

The comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) tests, offered by the University of Hong Kong’s faculty of medicine (HKUMed), were designed to target 1,800 patients with stage 4 non-small cell lung cancer in a bid to identify gene mutations.

The university’s Dr Victor Lee Ho-fun, the principal investigator in charge of the programme at Queen Mary Hospital in Pok Fu Lam, explained if the mutations could be identified, doctors might be able to devise personalised treatment for patients, instead of chemotherapy.

He added that if other mutations were found, which could also affect tumour growth and treatment response, doctors could plan early for scans and alternative treatments.

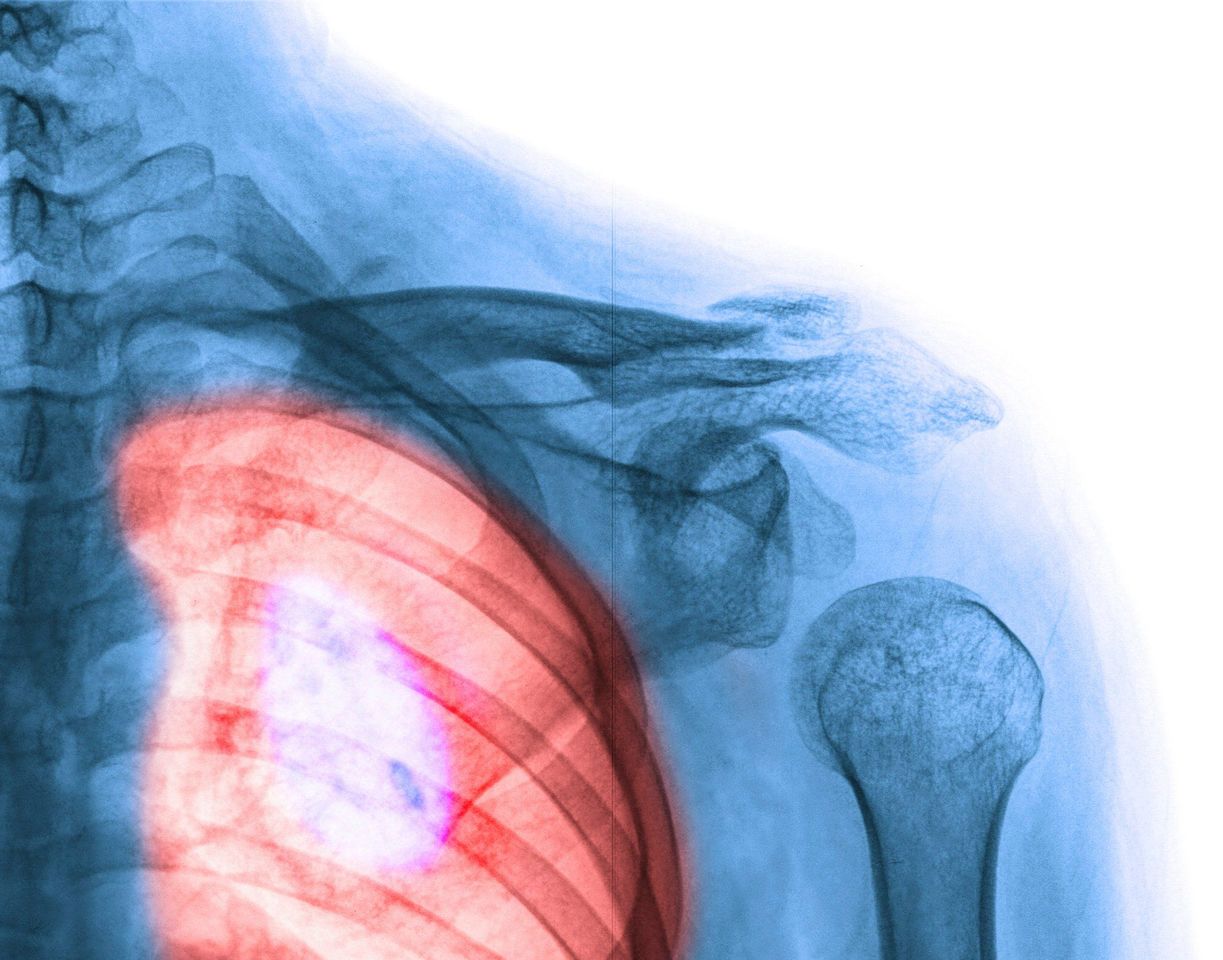

A lung affected by cancer.

A lung affected by cancer.Named after the size of cancerous cells, non-small cell lung cancer is the most common type of lung cancer in Hong Kong.

There were 5,422 patients with lung cancer in Hong Kong in 2020 and about four-fifths of them had non-small cell lung cancer.

The programme, which started in June last year, is a joint effort by the government, HKUMed and private healthcare company Roche Hong Kong.

It aims to recruit up to 1,800 patients for testing and treatment at seven public hospitals. Those eligible can apply through HKUMed’s department of clinical oncology.

The test to analyse the gene mutations can be done on tumour samples obtained through a biopsy or on blood samples.

CGP tests are available at private institutions, but cost about HK$50,000 (US$6,423).

Lee said, without the programme, public hospitals could only carry out basic tests for just three gene mutations.

If the three were not identified, patients would receive the standard treatment of chemotherapy, which has major side effects, including hair loss, poor appetite and a weakened immune system.

Lee said chemotherapy was “usually very toxic” as it not only killed tumour cells, but could also kill normal cells, especially in a patient’s bone marrow.

Patients with stage 4 non-small cell lung cancer survive for an average of 1½ to two years after receiving chemotherapy.

An alternative treatment with fewer side effects would involve using drugs that target the cancer cells only. Eight to 10 of the 300 gene mutations can be inhibited by such drugs.

Lee said patients treated with targeted drugs might, on average, survive for three to four years afterwards.

A 58-year-old patient, who asked to be identified only by the surname Wong, said she was diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer and underwent tests through the programme earlier this year.

“I could only receive conventional chemotherapy before joining the programme,” she said.

The test identified the gene mutations she had, and she was prescribed targeted drugs.

Wong said she considered herself lucky to be on the programme.

“The targeted drugs work for me and I find myself getting better,” she said.

Lee said some targeted drugs had not yet been approved for use in Hong Kong, but if patients needed them, doctors could liaise with pharmaceutical companies to obtain them on compassionate grounds or arrange clinical trials.

A total of 152 patients have undergone CGP tests so far and 30 per cent of them had gene mutations other than the three types public hospitals checked for.

Lee added that information collected in Hong Kong would fill the knowledge gap elsewhere in Asia, where these tests were not routinely done, and could help shape the treatment of Chinese patients.

The Innovation, Technology and Industry Bureau funded the programme with Roche Hong Kong, which also provided the technology for the tests.

HKUMed collects the information with the Hospital Authority, which follows up with patients.

Gareth Lane, who represents Roche Hong Kong in the programme, said collaborations between the government, the private sector and academics could be used to solve other problems in public healthcare.