Hong Kong News

‘Film distributor stopped screening of Winnie the Pooh horror flick in Hong Kong’

Hong Kong’s culture chief has said the distributor of a British horror film featuring children’s character Winnie the Pooh was behind the decision to cancel its screening in local cinemas, not the government, adding that the film had already gone through the city’s censorship body.

Secretary for Culture, Sports and Tourism Kevin Yeung Yun-hung on Wednesday said he had only found out about the cancellation of the screening of Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey through the news the day before.

“To my knowledge, it had been approved by the Film Censorship Authority and classified as a category III film,” Yeung said. “In the end, the film’s distributor decided not to show the film in Hong Kong for the time being. This is the distributor’s decision.”

Secretary for Culture, Sports and Tourism Kevin Yeung.

Secretary for Culture, Sports and Tourism Kevin Yeung.

On Tuesday, VII Pillars Entertainment, the local distributor of the film, announced the cancellation of the flick’s scheduled release in Hong Kong and Macau for Friday without stating a reason.

This came after an advance screening of the film on Monday, organised by local film critic Moviematic, was called off at the last minute over “technical reasons”.

Directed by British filmmaker Rhys Frake-Waterfield, Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey is a horror film reinterpreting British author A.A. Milne’s famous anthropomorphic teddy bear cartoon Winnie the Pooh.

The character has been used satirically, both inside and outside China, to represent Chinese President Xi Jinping in the past.

The comparison began in 2013 when an image of Xi and then-United States president Barack Obama prompted a joke on the internet, where Xi was likened to the bear, and Obama to the fictional tiger.

In 2017, mainland censors blocked posts with the Chinese name of the character as well as animated GIFs of the bear on mainland social media platforms without giving any reasons. A year later, Christopher Robin, a live-action film about Winnie the Pooh, was denied release on the mainland, without any explanation.

Responding to a Post inquiry, a spokeswoman for the Office of Film, Newspaper and Article Administration (OFNAA) confirmed that it had issued a certificate of approval for the film.

“The arrangements of cinemas in Hong Kong on the screening of individual films with certificates of approval in their premises are the commercial decisions of the cinemas concerned, and OFNAA would not comment on such arrangements,” the spokeswoman said.

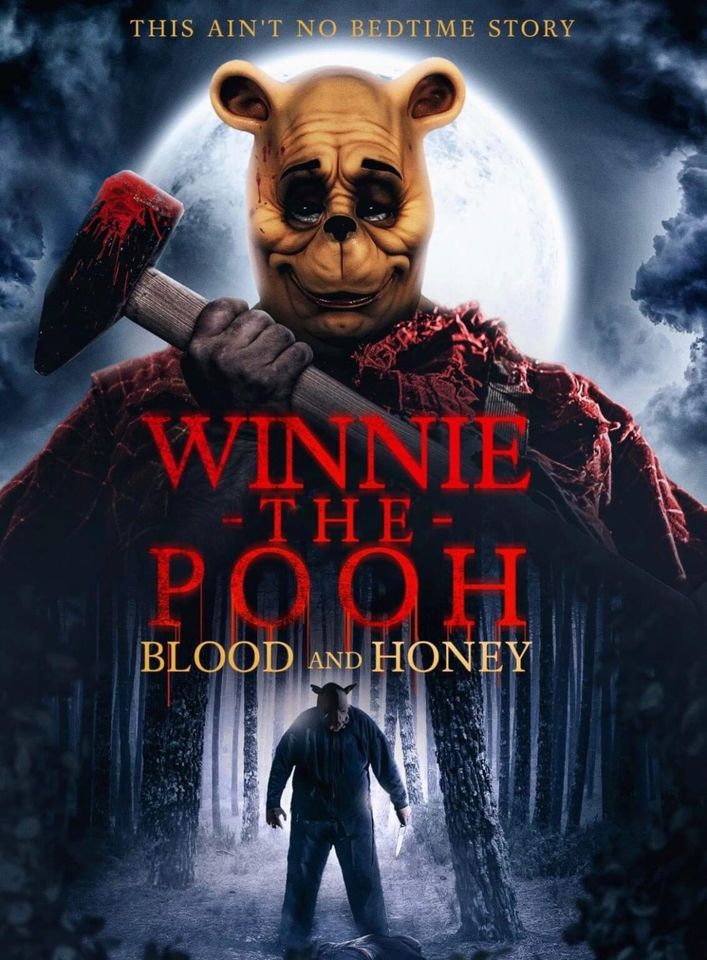

A movie poster of Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey.

A movie poster of Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey.

Director Frake-Waterfield told local media that his work had no intention to satirise Xi, as he had only wished to produce a horror film on the beloved children’s character.

The Post has reached out to Frake-Waterfield, VII Pillars Entertainment and Moviematic for comment.

Kenny Ng Kwok-kwan, director of the Centre for Film and Moving Image Research at the Baptist University, said that a lack of explanation about the unexpected halt would spark concerns over self-censorship in the city’s cinemas, adding that back door negotiations between film houses and authorities had occurred in the past.

“Should the censorship body have banned the film earlier, it would have ignited even more controversies, speculations and pressure in society and internationally,” Ng said.

“The act of withdrawing a licensed film from public exhibition may not be too surprising in the current situation or indeed has become a decent way of respecting the red line.”

Ng added that censorship did not simply lie with vetting authorities.

In March 2021, Inside the Red Brick Wall, a controversial documentary portraying fierce clashes at Polytechnic University during the 2019 anti-government protests, was pulled hours before its scheduled cinema screening, following warnings it could be in breach of the Beijing-imposed national security law.

Later in 2021, the legislature passed a bill to toughen Hong Kong’s film censorship, authorising the city’s No 2 official to ban productions that undermined national security and increasing the maximum jail term for anyone who screened films already classified as a threat.