Hong Kong News

Ex-chief justice Geoffrey Ma defends role of foreign judges in Hong Kong

Former Hong Kong chief justice Geoffrey Ma Tao-li has defended the role of foreign judges in the city, arguing they should continue to sit on the bench and help enforce the mini-constitution which he described as the basis of judicial independence.

In his first major public engagement since stepping down in January this year, Ma’s comment appeared to target Western critics who had urged foreign judges in Hong Kong to quit as a matter of protest in the wake of the enactment of the Beijing-imposed national security law.

Ma, Hong Kong’s top judge from September 2010 to January this year, said while critics focused on provisions of the security law that allowed Beijing to exercise jurisdiction over complex cases, they should also take into account its references to human rights and the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution.

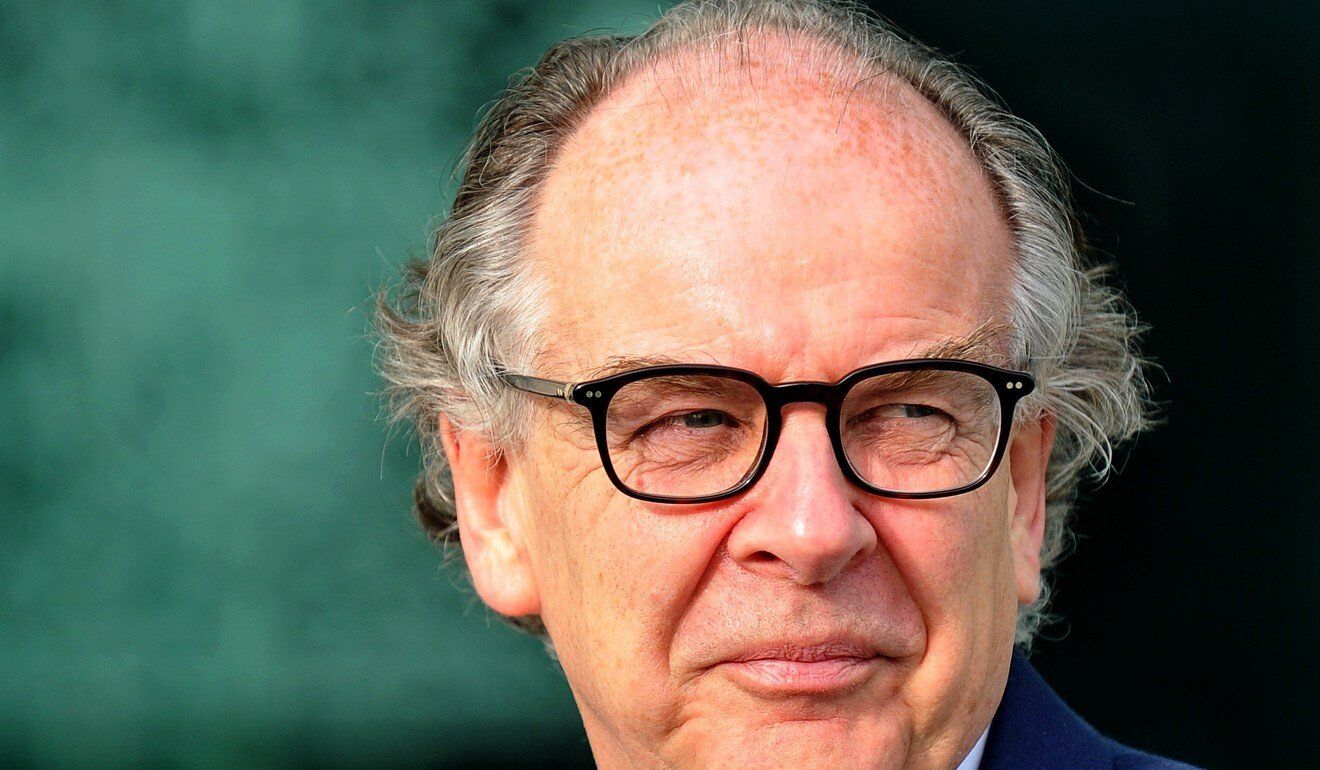

Former Hong Kong chief justice Geoffrey Ma.

Former Hong Kong chief justice Geoffrey Ma.

“[The Basic Law] prescribes for an independent judiciary … sets out freedoms and human rights, [and] links it internationally to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,” he said.

“All these matters are stated in the Basic Law, reflected in the judicial oath, and when a judge comes [and] is in Hong Kong, that person … is duty-bound indeed, and has taken an oath to enforce the Basic Law.”

Ma also clarified that he did not describe a condition in the legislation as a “strange provision” in remarks made in March. Instead, he argued, it was others who found it strange that the security law allowed the city’s leader, after consulting the chief justice, to designate judges to handle national security cases.

Former British Lord Chancellor Charles Falconer.

Former British Lord Chancellor Charles Falconer.

Ma was speaking in a webinar on the future of law and business in Hong Kong. The discussion was organised by British-based group The Legal 500, and local law firm Haldanes.

Other speakers at the webinar were: former British Lord Chancellor Charles Falconer, criminal lawyer Jonathan Midgley; veteran lawyer Jonathan Caplan QC; and Professor Lin Feng, associate law dean at the City University of Hong Kong.

In March, British Supreme Court president Robert Reed said he would weigh resigning as a non-permanent judge on the Court of Final Appeal should he conclude that judicial independence had been compromised. Falconer, who has been a vocal critic of Beijing’s policies on Hong Kong, had suggested that Reed should quit.

Asked to elaborate on his rationale, Falconer on Wednesday said: “I do not think that the pinnacle of the UK legal system should [give] due credibility to a system where there is a massive hole in the rule of law in Hong Kong.”

Falconer argued that the national security law “indicates that a central basis of the rule of law in Hong Kong is gone”. He said it was most exemplified by Article 55 of the security law, which allows the city’s government to ask Beijing to exercise jurisdiction over a national security case if it is complex, when a serious situation occurs and the city’s government is unable to effectively enforce the law, or when a major and imminent threat to national security has occurred.

Falconer described the article as giving executive authorities an alternative route to the city’s legal system.

“This healthily functioning system of high-quality judges were able to resolve, for example, non-political criminal cases … but running alongside it, is the option for the Chinese government to pick up on those they don’t like and deal with them outside the established legal system, and that is why the rule of law is now a charade,” he said.

Ma questioned whether Article 55 was a sound basis for Falconer to suggest that the rule of law was severely compromised in Hong Kong, and that Britain’s top judges should resign from Hong Kong courts.

“Lord Falconer takes [Article 55] to mean: if you don’t like the result, we’ll have another go. Well, [the article] doesn’t say that, and to say that it does, is actually speculation.”

Lin said at the webinar that Article 55 would only be invoked if Hong Kong faced an emergency situation endangering national security.

Caplan also said he suspected that Article 55 would recede and become a redundant provision.

He argued that most states “actually depart from the rule of law and natural processes” in handling national security cases.

Midgley, senior partner with Haldanes, also said Hong Kong’s legal system remained sound.

“It’s a great shame that there is a suggestion from overseas that this system is in some way broken … It simply isn’t. It is not a broken system, and the idea that people, particularly from England, are saying that Hong Kong is broken, I think, has turned into a political sport at the expense of those living here,” he said.

In March, Ma attended a webinar where panel members discussed whether it should be entirely up to the judiciary to assign judges to cases, without the involvement of the executive branch.

At the session, Ma noted the national security law had empowered the city’s leader to designate judges to hear cases under the legislation. “This is an important question as far as Hong Kong is concerned, where you have the strange provision of the designation of judges,” he said.

Ma’s remark was interpreted by pundits as indicating he found the provision odd, but he claimed on Wednesday he was misquoted.

“What I was doing in that particular talk … was saying that some people have regarded that provision in the national security law as being odd or strange,” he said.

“I never comment on legislation, say this is good, great, bad or strange, I never do that and never will.”