Hong Kong News

Blood on the tracks as Hong Kong’s boar war begins

It was just after sunset one day last month when veterinary surgeons Karthi and Paolo Martelli arrived at a village in Hong Kong’s New Territories with Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department (AFCD) staff to tranquillise wild boars in the area and move them elsewhere.

The husband-and-wife team has spearheaded a drive since 2017 to rein in the city’s wild boar population by using a contraceptive vaccine and sterilisation.

That evening, however, they could not get started. An argument broke out between a farmer whose crops had been destroyed by boars and who wanted them removed, and a group of villagers who had been feeding the animals and insisted that they be allowed to stay.

“We could not do anything. We just sat and watched while people were screaming at each other,” Karthi Martelli said.

When both sides refused to budge, the team of about 20 called off their mission, packed up and left.

The scene that evening reflected the divide over wild boars in Hong Kong, with animal-lovers facing off against others demanding action against the animals, which they considered a nuisance and even dangerous.

Urban jungle

Videos of wild boars venturing into urban areas have become common in recent years, including ones showing a family of boars frolicking in a fountain outside a Bank of China branch in Central and young boars riding the MTR.

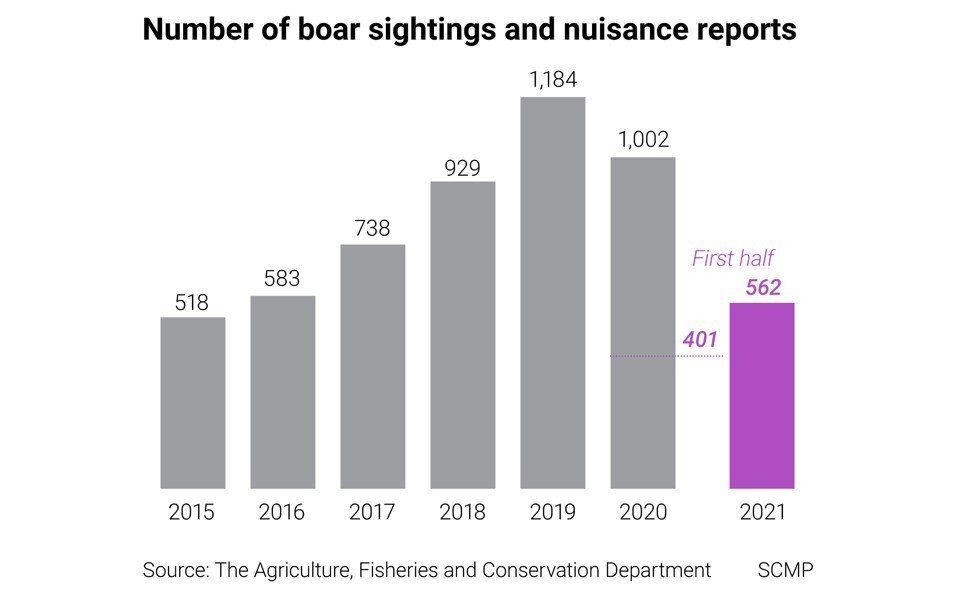

Over the past decade, the number of sightings and nuisance reports involving boars rose from 225 in 2011 to 1,002 last year. There were 36 injury cases caused by wild pigs over the past 10 years, with four in five occurring since 2018. And in the first half of this year alone, authorities received 562 reports of boar sightings or them causing a nuisance.

In September, pop star Coco Lee’s mother fell after being attacked by a boar while on a walk near her home on The Peak. Frances Wang, 83, needed five hours of surgery for a shattered elbow and fractured hip.

A wild boar piglet on an MTR train in June.

A wild boar piglet on an MTR train in June.

On November 10, a part-time police officer was knocked down and bitten in the leg by a boar outside a high-rise block in Tin Hau in bustling Causeway Bay. The animal then fell to its death from the building’s car park.

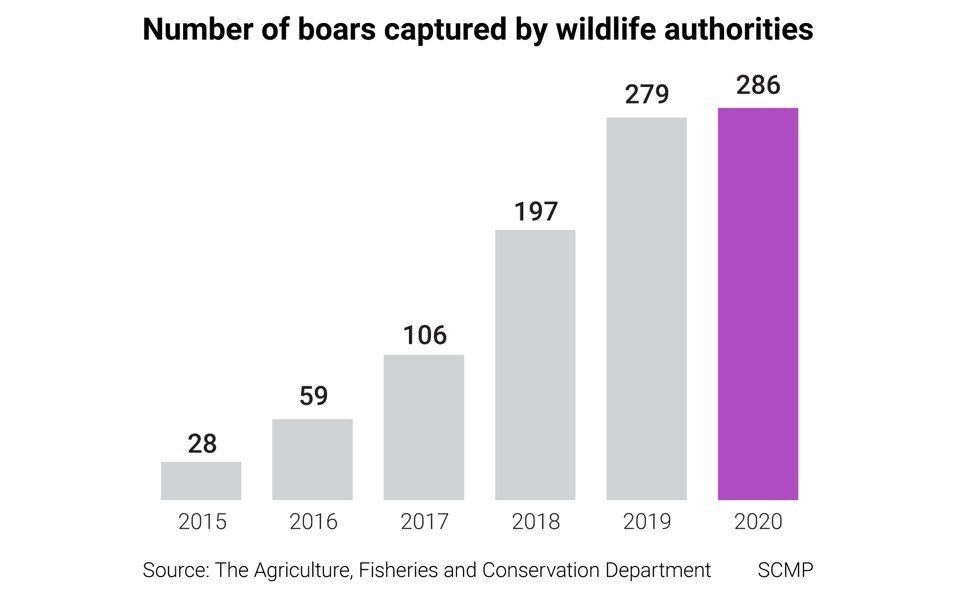

Two days later, the AFCD said boars found in urban areas would be “captured for humane dispatch with a view to reducing their number and nuisance”.

This week, authorities acted. On Wednesday evening, an AFCD team captured and put down seven boars found in Wong Chuk Hang on southern Hong Kong Island.

The operation took place on Shum Wan Road, where there have been regular boar sightings and people have been known to feed the animals. A widely circulated video showed a group of boars in the area chasing after a taxi whose passenger was suspected of feeding them.

The action was criticised by animal rights groups and over social media, but the AFCD said it would carry out such operations regularly, with “priority to sites with large numbers of wild pigs, and locations with past injury cases or with wild pigs that may pose risks to members of the public”.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor defended the new policy of culling boars found in built-up areas, saying on Tuesday authorities were also considering increasing fines for feeding wild animals.

Dr Howard Wong Kai-hay, director for development of veterinary medicine at City University, said the wild boars were capable of killing a person, for example if an individual approached a mother boar with piglets.

“I think we have been very lucky that a very serious injury has not happened so far,” he said. “The clock is ticking. It really is a matter of when, not if.”

Nikolaus Osterrieder, dean of the Jockey Club College of Veterinary Medicine and Life Sciences at City University, said the boar problem was likely to worsen in terms of conflicts between humans and animals, unless the boar population was controlled, including by contraception and sterilisation.

He said the problem was not unique to Hong Kong, as Japan, Germany and Spain were among countries also dealing with boars straying into urban areas.

Osterrieder is from Berlin, where the boar population has grown and the animals are referred to as a “plague”. It is one of the places where hunting is permitted as a way to control the population.

Hong Kong used to allow a group of volunteers to carry out hunting operations when there were reports of damage or attacks caused by wild boars, but the practice was suspended in 2017.

International research has shown that global climate change has also contributed to the growth of wild boar populations as warmer weather has increased the availability of food and eased winter conditions.

“The wild boar [are] among the clear winners of global climate change,” a study in science journal Nature published last year said, adding climate change was likely to continue or even accelerate population growth.

A more humane way

The Martellis – he is Italian and his wife, Malaysian – are veterinary surgeons at Ocean Park and say they believe contraceptive vaccines and sterilisation are the more humane way of controlling the boar population.

They have been going out twice a month since 2017 with a team of about 20, including veterinary surgeons, nurses and AFCD officers to administer contraceptives, sterilise and move the wild pigs to other locations.

Starting in late evening, they go to locations suggested by the department and typically work on about six boars, though they have done up to 13. Sometimes they manage to do only one, as the animals get away quickly.

The animals are first tranquillised, measured and microchipped. The females are scanned to check whether they are pregnant.

Paolo Martelli, director of veterinary services at Ocean Park, performs sterilisation by keyhole surgery on male and female pigs on tables able to take animals up to 100kg.

“It takes less than 10 minutes. The difficulty is putting them in position and then putting on a mask for oxygen. The surgical time is short, anywhere between three and five minutes,” he said.

He noted the joint operations with the AFCD cost “millions of dollars” a year, which was a heavy price for taxpayers to bear simply because a few people fed wild boars.

As of October 31, 450 boars had been given contraceptive treatment or sterilised.

A wild boar approaches a man at Aberdeen Country Park.

A wild boar approaches a man at Aberdeen Country Park.

The role of residents

Critics say the programme has made little impact, given how quickly boars breed, with a sow able to have two litters of up to eight piglets a year.

Wild boars are not considered a protected species because their numbers are not threatened.

A preliminary study by the AFCD in 2019 estimated there were between 1,800 and 3,300 wild boars in countryside areas.

A department spokesman said that in general, the animals were naturally wary of humans. “However, they may bite if they are provoked or are attracted by food,” he added.

Experts said the animals had become a problem because their behaviour changed when people fed them or they found it easy to scavenge from garbage bins.

Paul Crow, senior conservation officer at Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden, said feeding a boar removed the animal’s natural fear of humans and vehicles.

Feeding them also contributed towards boosting their population artificially, because with an increase in the amount of food, they reproduced more.

“It discourages them from staying in the forest and is going to just draw them out more into conflict with people,” Crow added.

A wild boar family swims in a fountain outside the Bank of China tower in Central in September last year.

A wild boar family swims in a fountain outside the Bank of China tower in Central in September last year.

Paolo Martelli said the issue was not the number, but the appearance of boars in urban areas, attracted by garbage or food offered to them by people.

“If you have 1,000 boars in the bush, it’s not a problem. If you have one boar in the MTR train, it is a major problem,” he said.

He also referred to a video clip that went viral in September showing about 20 wild boars chasing a taxi along Shum Wan Road by the Aberdeen Marina Club.

Martelli said the taxi passenger was suspected of feeding the boars and, in fact, had been fined multiple times by the AFCD.

He added: “I have an ethical issue with some people feeding the pigs and other people coming to kill them.”

Alternatives to culling

Karthi Martelli said: “Repeat offenders should be given either a significantly larger fine or made to perform mandatory social services such as cleaning garbage or helping farmers install fences to prevent wild animals damaging their crops.

“They need to understand the repercussions of their actions, as often others pay the price, including the animals themselves. In a survey we did in Hong Kong, nine out of 10 people disapprove of feeding and think the feeders are selfish.”

Roni Wong Ho-yin, a committee member of the Hong Kong Wild Boar Concern Group, said improperly sealed refuse collection bins also led to the animals scavenging for food.

Currently, there are feeding bans in certain areas, such as Lion Rock and Shing Mun country parks, but not at Lung Fu Shan Country Park on Hong Kong Island.

The fines range from HK$200 (US$26) to HK$10, 000. The AFCD said there were 81 prosecutions this year, as of August 31, with fines ranging from HK$200 to HK$1,000 handed out. Last year, there were 38 prosecutions with fines of between HK$300 and HK$2,000.

The department is also exploring amending the Wild Animals Protection Ordinance to expand the areas where feeding is banned.

It said it had reinforced barriers at garbage bins and put up posters tell people to stop feeding wild animals.

Dr Fiona Woodhouse, deputy director of welfare at the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) pointed out that boars used to being fed could be more aggressive towards people with food.

The SPCA said long-term management of the boar population demanded a combination of methods, and interventions should be minimal.

Dr Billy Hau Chi-hang, programme director for master’s degrees in environmental management at the University of Hong Kong, felt lethal methods were necessary as the “softer” approach of education and awareness campaigns had not worked.

Having worked in the field with wild boars for 30 years, he said Kowloon Hills, Aberdeen Country Park and The Peak were areas where people fed boars.

“I don‘t know why some people have this strong desire to feed the animals,” he said. “It seems to me that education does not work on them.”