Hong Kong News

Beware: the US-China technology war is about to burst the tech bubble

Illustration: Craig StephensIllustration: Craig Stephens Illustration: Craig Stephens The US tech war with China is heating up, and it isn’t looking good for the tech bubble. The technology war will depress demand for the foreseeable future and increase business costs for all participants. The tech bubble is still floating high, with tech stocks surging as central banks boost liquidity in response to the pandemic.

But as the impact of the tech war becomes increasingly obvious over the coming quarters and earnings reporting seasons, a chill will be thrown over stock markets. There might not be enough liquidity to neutralise fears over deteriorating fundamentals. When this tech bubble bursts, the popping sound could be louder than in 2000 and send more shivers through financial markets than the crisis in 2008.

The world is seeing the biggest tech bubble in history. Look no further than Apple , which has reached US$2 trillion in market value. Even though Apple is a good company with a sustainable business model, its core business of mobile phones is a sunset market. Given that it is already a tech giant, how much room is there for growth? Yet its price-to-earnings ratio – close to 40 times – is its highest in a decade, which just doesn’t make sense.

The valuation of other tech companies makes even less sense. Tesla may be the world’s largest car company by market value, but it is actually a small company by revenue in an industry – and a segment of the industry – with massive overcapacity.

Uber is a ride-hailing business that can grow rapidly only by slashing prices. Companies like Facebook and Google profit from collecting data and are increasingly coming under regulatory scrutiny. It is doubtful that their business model is sustainable.

Excessive liquidity is the reason for the massive bubble. Some might still remember the Y2K bubble. Back then, the world was seized by the fear that all computers would stop working at midnight on December 31, 1999.

Major central banks like the Federal Reserve bought into it and ramped up liquidity support. This fed a dotcom boom. When central banks normalised policies in 2000, that bubble popped.

The current bubble is much bigger; Covid-19 is a real crisis, unlike the Y2K bug; and the global economy is in its deepest trouble since the Great Depression.

Yet, central banks have followed their usual playbook, chopping interest rates to zero and pouring trillions into the global banking system.

How would this help the real economy? Cutting rates works by encouraging investment and consumption. When the bottleneck is millions of people stuck at home, that is, demand can’t respond to financial incentives, how would more liquidity help?

The only visible consequence now is a massive bubble. Central banks have probably made the biggest mistake of their lives. When this bubble pops, their reputation may never recover.

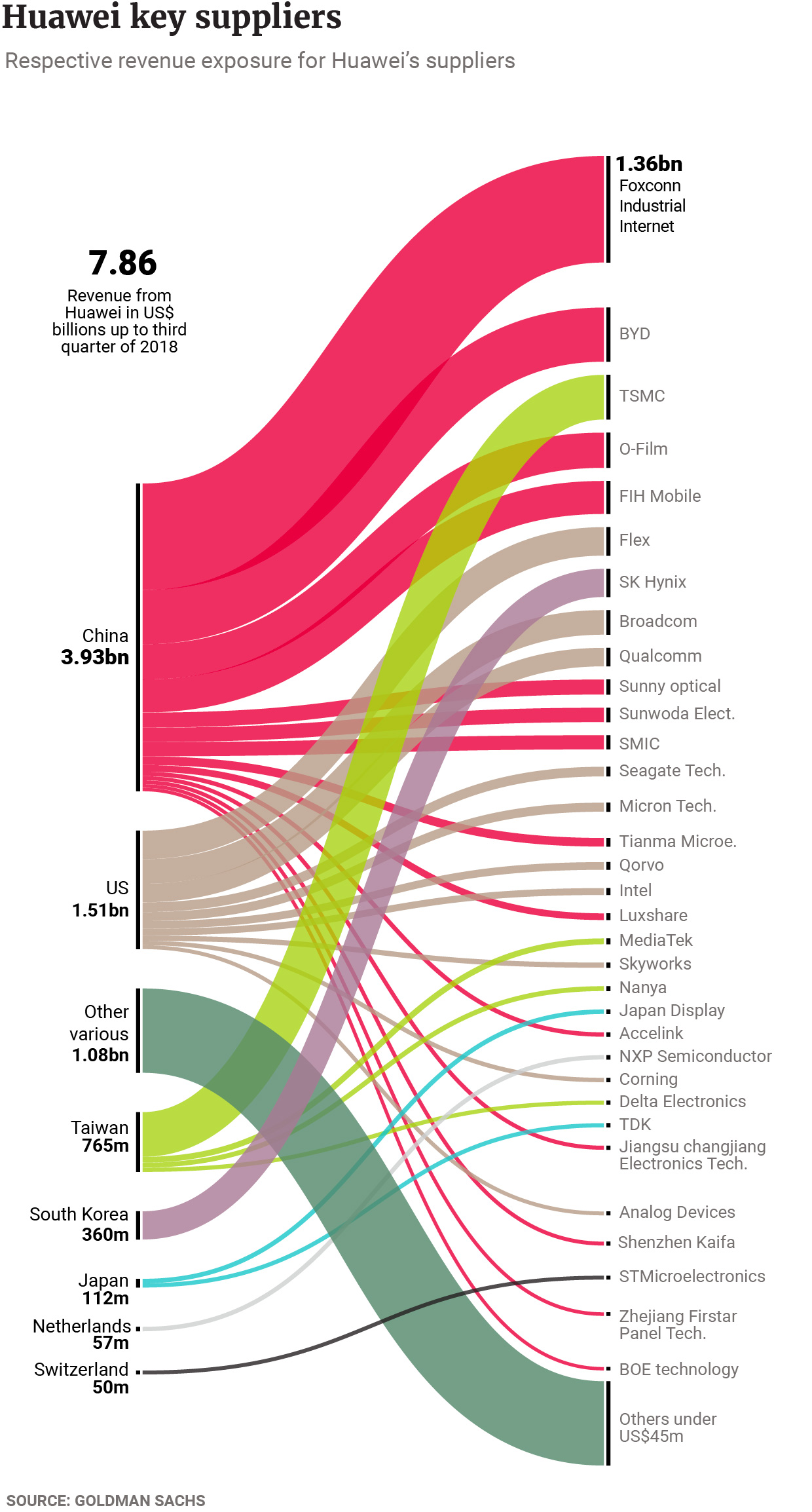

Dark clouds are gathering over speculators. The Sino-US rivalry will define the 21st century. The US’ tariff war with China was a start. Now, the tech war is intensifying, with Washington essentially choking off Huawei’s chip supply.

Since the Chinese company is the world’s largest supplier of telecoms equipment, its demand for chips accounts for a big chunk of the market. It would take a long time for Huawei’s competitors to develop the same capacity. The global demand for chips could decline for several years.

The decoupling of the US from China, and the reshaping of global supply chains, is inevitable – but the process might take many years. It will slow innovation, reversing a trend of the past two decades.

China has long been a paradise for producers of IT goods. One could take a design to China and have it made quickly, cheaply and in massive quantities.

There is no real alternative to China. What comes after this is a supply chain spread across many countries, with much higher labour and capital costs and less efficient logistics.

For brand companies like Apple and vending platforms like Amazon, this will mean rising costs and declining margins, unlike what they are used to. This also means that financial markets can’t extrapolate from past trends any more and that shares may have to be repriced.

With the US-China decoupling, the global economic slowdown will last beyond the pandemic. These two economies have accounted for most of global growth in the past two decades; other economies have pretty much been piggybacking on their success.

US demands for TikTok may escalate decoupling and hurt businesses, says China expert

China is an economy that overinvests, while the US overconsumes: a marriage of convenience allowed these two one-legged individuals to lean on each other and keep their balance. But as they lean away from each other now, they are bound to stumble.

Normalcy could return when they balance their economies. However, neither has been doing that so far.

A slower global economy would have a big impact on the tech sector. This is because the sector is driven by consumption, and will be affected by income growth or lack thereof. Already, demand for mobile phones is shifting from the high end towards the lower end.

Demand for IT goods is so strong now that the sector behaves like other markets, with regard to income. For now, the coronavirus-induced income decline has been offset by governments’ helicopter money. But governments cannot borrow forever to support people’s consumption. The impact of Covid-19 on demand for IT goods has been merely delayed, not nullified.

The IT goods market is like any other consumer market. It will mature. And it is maturing during what is likely to be a prolonged economic slowdown. When investors realise that the IT goods market is moving close to where the white goods market was two decades ago – entering years of slow growth and declining margins – the bubble will pop.