Hong Kong News

As Hong Kong limits June 4 vigils, activists in US say ‘don’t forget’

In a small corner of San Francisco’s bustling Chinatown, silence fell for a brief moment on Thursday evening as some 200 people gathered to mark 32 years since Beijing’s bloody crackdown of student-led calls for democracy.

Leading the moment of silence was Fang Zheng, a survivor of the 1989 violence. He addressed the gathered crowd 32 years – almost to the hour – after he fell beneath one of the tanks deployed by the Chinese government to clear Tiananmen Square of the thousands of students gathered there.

Fang’s legs, crushed by the tank’s tracks, were later amputated.

“Thirty-two years have passed, we’ve never forgotten this tragedy,” said Fang, a former track-and-field star who settled in California. “Moreover, we’ll never give up our pursuit of the truth, nor will we give up seeking accountability for this crime.”

Thursday night’s vigil, an annual fixture in San Francisco’s Portsmouth Square, was just one of numerous events held by activists in the United States – both on- and offline – to honour those killed in 1989.

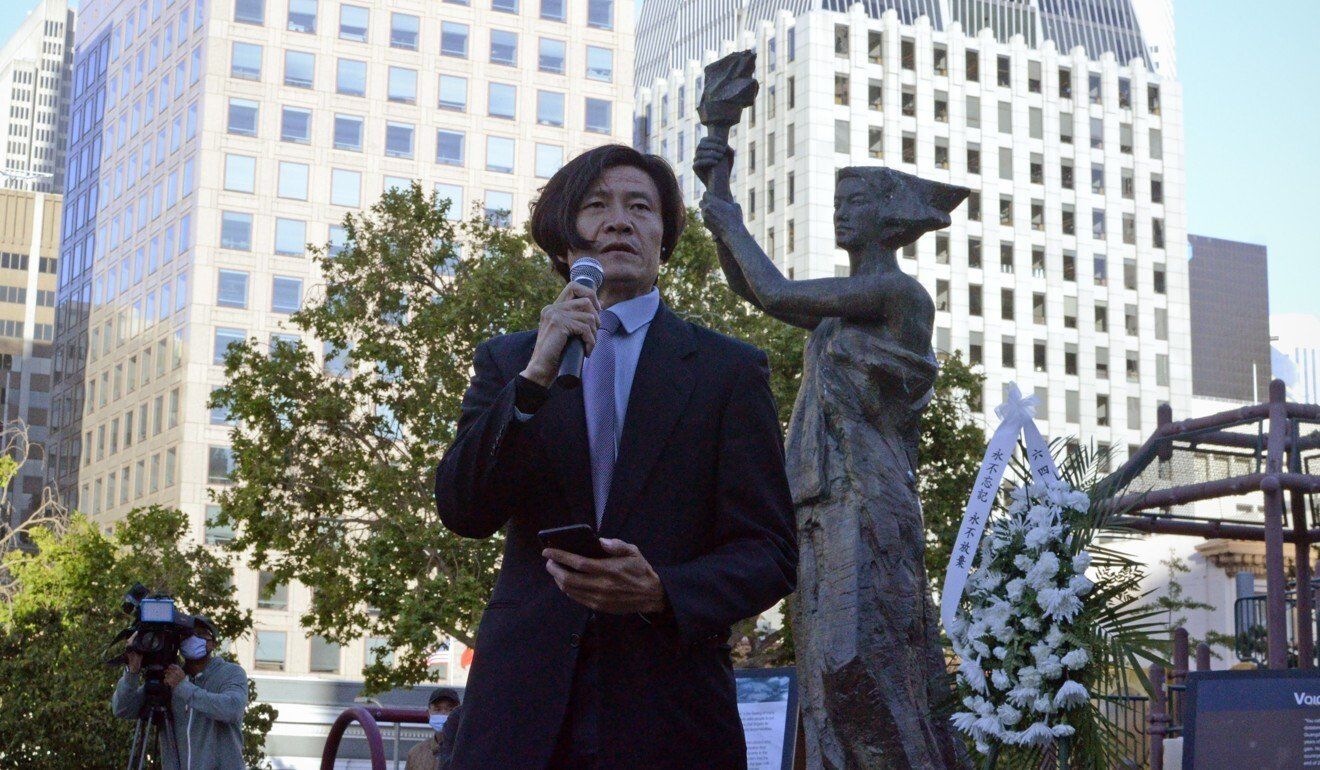

Fang Zheng, who lost both legs after being crushed by a tank on June 4,

1989, speaks at a vigil in San Francisco marking the 32nd anniversary of

the crackdown.

Fang Zheng, who lost both legs after being crushed by a tank on June 4,

1989, speaks at a vigil in San Francisco marking the 32nd anniversary of

the crackdown.

Despite frigid temperatures and the continuing pandemic, the gathering was among the highest attended in the San Francisco vigil’s history, according to long-time participant Zhou Fengsuo, a New York-based activist and erstwhile leader of the 1989 movement.

Looking over Zhou and the other speakers as they addressed the crowd was a 10-foot replica of the Goddess of Democracy statue erected by students on Tiananmen Square. As darkness fell at the close of the vigil, attendees gathered before the bronze replica to place white flowers and battery-operated candles.

Among those who came to Chinatown to pay their respects was Dave, a 24-year-old from China, who spent the entirety of Thursday’s two-hour vigil standing atop a wall brandishing a large flag of the Republic of China.

“They could kill those students, but they can’t kill the true free spirits of all the Chinese people,” said Dave. “I was born later [than 1989], but I know their story, and I want to pick up their flag and keep marching forward.”

Like a number of other attendees who spoke to the South China Morning Post, Dave declined to give his full name. The crackdown remains one of the most sensitive and heavily censored subjects in China, where the government says that it correctly handled what it refers to as “political turbulence”.

In rare public comments about the crackdown in 2019, China’s Defence Minister Wei Fenghe said that due the central government’s “decisive” action in stopping the protests, “China has enjoyed stability” in the years since.

The Chinese embassy did not respond to a request for comment on the anniversary.

For many activists, the commemorative activities have taken on particular weight given the erosion of civil liberties in Hong Kong, the long-time global epicentre of memorials to the crackdown.

This year’s June 4 anniversary is the first to occur since the implementation of Hong Kong’s sweeping national security law, legislation forced through by Beijing that criminalises four broadly defined categories of behaviour.

Its introduction has led to dozens of arrests of activists, lawmakers and journalists and prompted growing fears of self-censorship, with two Hong Kong teachers recently telling the Post they would drop Tiananmen Square from their syllabus, citing concerns of crossing red lines under the law.

And for the second year in a row, authorities have cancelled the annual commemorative ceremony in Hong Kong’s Victoria Park, forcing residents to commemorate the crackdown in more ad hoc or private ways. Held since 1990 and attended yearly by tens of thousands of Hongkongers, the iconic candlelight vigil constituted the only large-scale commemoration of Beijing’s bloody crackdown on Chinese soil.

Even as daily coronavirus cases dwindle into the single digits, the city government has cited public health concerns for the move, while threatening stringent sentences for anyone participating in or promoting June 4 events: five- or one-year prison sentences, respectively.

And on Wednesday, Hong Kong’s June 4 museum, free to the public, was forced to close its doors in the wake of a licensing investigation begun by the city. Activists and US officials interpreted the move as another indicator of declining freedoms in the city.

“Hong Kong and Beijing authorities continue to silence dissenting voices by also attempting to erase the horrific massacre from history,” US State Department spokeswoman Jalina Porter told reporters on Wednesday.

Hong Kong loomed large over Thursday’s crowd, which on numerous occasions burst spontaneously into cries in Cantonese of “Liberate Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Time”, the de facto slogan of pro-democracy protests in the city over recent years. Some attendees also brandished flags calling for Hong Kong’s independence.

Among them was Jennifer, a San Francisco resident originally from Hong Kong, who described the confluence of June 4 commemoration with the situation facing her home city as “heartbreaking”.

“The CCP is trying to cover up this Tiananmen massacre that happened years ago, and it cannot be forgiven, it cannot be forgotten,” said Jennifer, who declined to give her full name. “We’re here to show support.”

To those who themselves participated in the pro-democracy movement of 1989, the dwindling opportunities for Chinese people to publicly commemorate the crackdown represented an urgent call to action.

Feng Congde, a former student leader, addresses the crowd at the San Francisco vigil honouring those killed in 1989.

Feng Congde, a former student leader, addresses the crowd at the San Francisco vigil honouring those killed in 1989.

The Victoria Park vigil was “the fortress of this memory”, Zhou, the former student leader who once was ranked fifth on Beijing’s most wanted list, said in a recent interview. It was that fortress’s collapse, the 53-year-old said, that had spurred him to organise a recent 24-hour online vigil this week. “That’s always in my mind. That’s why I want to do this.”

Broadcast across multiple digital platforms from Thursday to Friday, the online vigil featured addresses by student leaders, footage of people lighting their own candles in private and photographs of the demonstrations 32 years ago.

“I’m in China and jumped the firewall to watch this stream,” one viewer wrote in Chinese beneath the YouTube feed on Thursday. “May the dead rest in peace.”

The online memorial was markedly less eventful than a similar vigil convened by Zhou last year, when videoconferencing company Zoom disabled the organisers’ account because individuals based in China had dialled in to the event. Amid a public outcry, Zoom swiftly reinstated the account and fired a China-based executive, who was indicted by the US Department of Justice over the episode.

After last year’s controversy, a US law enforcement official sat in on this week’s online vigil to monitor for any disruption, according to a source familiar with the event’s planning.

The marathon vigil capped off more than six weeks of online programming organised by Zhou to commemorate June 4.

Since April 15, for four hours each morning, Zhou and a small group of volunteers have hosted sessions on live audio app Clubhouse, where participants in and scholars of the Tiananmen movement share memories to help piece together the events of each corresponding day in 1989, leading up to June 4.

It was both a “fact finding” and “soul searching” mission, Zhou said. By his count, it also represented the largest gathering – albeit online – of the movement’s student leaders since 1991.

“My most important contribution on Tiananmen Square, which I’m still proud of, [was] to make it like a freedom forum,” Zhou said, recalling the radio broadcast station he set up at the square with other students. “It was the only time in Chinese history where people could express [themselves] so freely … at the centre of political power.”

Zhou Fengsuo, a former student leader, speaks to the crowd in San

Francisco on Thursday. Behind him is a 10-foot replica of the Goddess of

Democracy statue.

Zhou Fengsuo, a former student leader, speaks to the crowd in San

Francisco on Thursday. Behind him is a 10-foot replica of the Goddess of

Democracy statue.

Thirty-two years later, the same desire to create a platform for open dialogue is evident in the way Zhou discussed his Clubhouse series. “This, to me, is the same thing,” he said. “We want different people to talk and express their thoughts.”

One such participant was Wang Liang, a Chinese artist now pursuing postgraduate studies in the US.

For the past 20 years, the 38-year-old has opted not to eat on the day of June 4 – his way of commemorating the hundreds of students who took part in a hunger strike in 1989.

Wang has also produced artwork and music to memorialise the events of June 4, ranging from an intricate painting of 30 flowers to mark three decades since the crackdown to an adaptation of Auld Lang Syne, which he performed to close out one recent Clubhouse session. (The future’s bright, we’ll meet again, when we gather on the square, Wang sang).

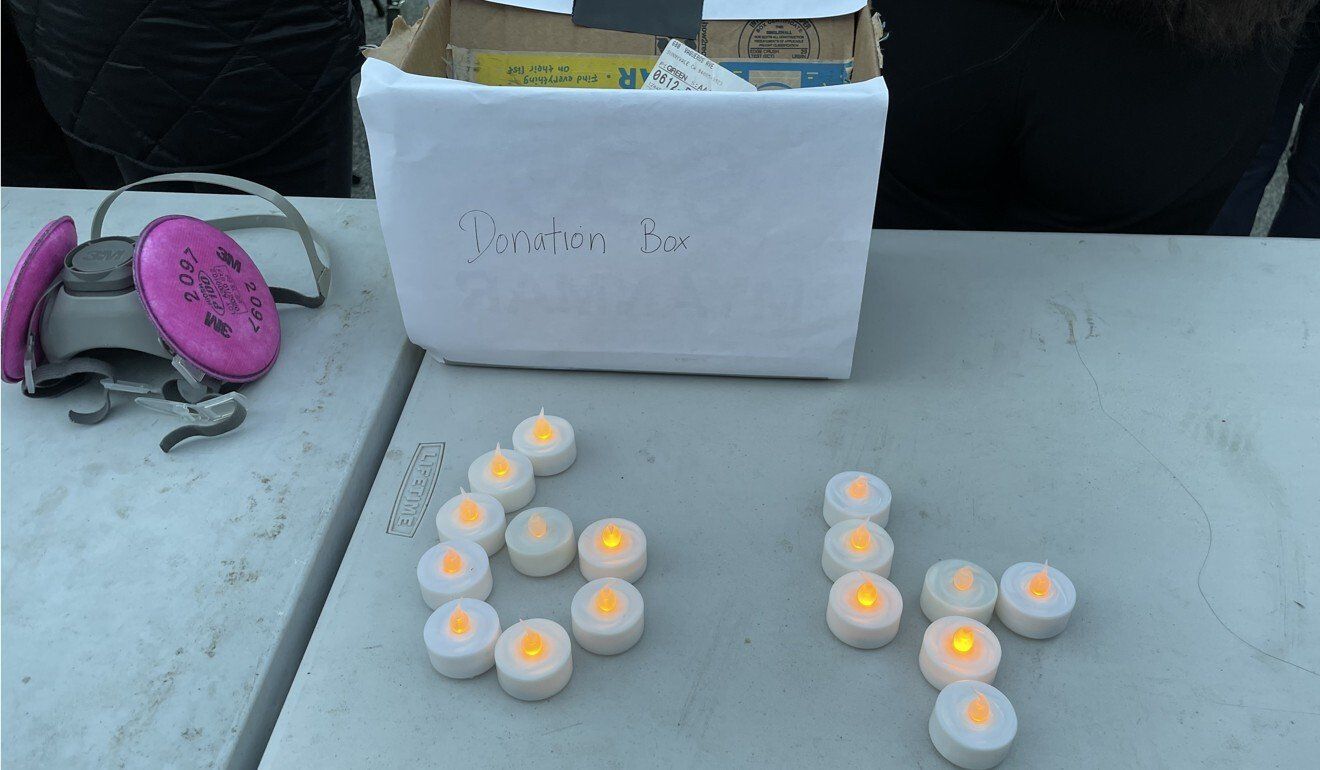

Candles are arranged to represent June 4 at a San Francisco vigil marking 32 years since the Tiananmen Square crackdown.

Candles are arranged to represent June 4 at a San Francisco vigil marking 32 years since the Tiananmen Square crackdown.

For Wang, born some seven years before the events of Tiananmen Square, memorialising the violent crackdown should be both an act of remembrance and an opportunity for those aggrieved by Beijing to band together and push for “transformative change” to China’s political system.

“I hope that we approach June 4th with more than just sorrowful commemoration and memories,” said Wang, who also goes by the name Xiuming.

Wang, who hopes to return to China to one day participate in a more democratic political system, appeared clear-eyed about the possible effect his advocacy and participation in June 4th commemorations could have on his personal situation should he go back.

“Someone has to tell the truth,” Wang said. Using a euphemism to describe being questioned by Chinese police, he quipped: “If I get invited for tea then I get invited for tea.”