Hong Kong News

Analysis: Credit Suisse collapse threatens Switzerland's wealth management crown

Battered by years of scandals and losses, Credit Suisse had been fighting a crisis of confidence for months, before its demise was sealed in just a matter of days last week when Swiss authorities brokered a takeover of the bank by larger rival UBS.

UBS itself needed to be rescued by the government in 2008 after a disastrous foray into U.S. mortgage securities.

The Credit Suisse collapse and its aftermath "is going to be very damaging," said Arturo Bris, Professor of Finance at the International Institute for Management Development (IMD) in Lausanne, adding it could benefit rival financial centres.

Switzerland manages $2.6 trillion in international assets according to a 2021 Deloitte study, making it the world's largest financial centre ahead of Britain and the United States. But it faces competition from other centres including Luxembourg and in particular Singapore, which has grown rapidly in recent years.

"The bankers in Singapore are going to be uncorking the champagne bottles," Bris told Reuters.

Switzerland's credibility as a stable, predictable country had been upended by moves like the decision to wipe out the holdings of Credit Suisse bondholders, he said.

Under the takeover deal, holders of Credit Suisse AT1 bonds will get nothing, while shareholders, who usually rank below bondholders in compensation terms, will receive $3.23 billion.

While Credit Suisse's AT1 prospectus made clear that hybrid (AT1) holders would not recover any value, few anticipated the bank's demise.

The Swiss Bankers Association has attempted to put a brave face on the crisis, presenting the rescue engineered by the government, central bank and regulator as sign of strength.

"The Swiss financial sector was able to address a major issue of a significant player," SBA Chairman and former UBS CEO Marcel Rohner told reporters on Tuesday.

"In that sense I also see a prosperous future for the financial centre because we have hundreds of very well capitalised banks and very successful wealth management and asset management banks."

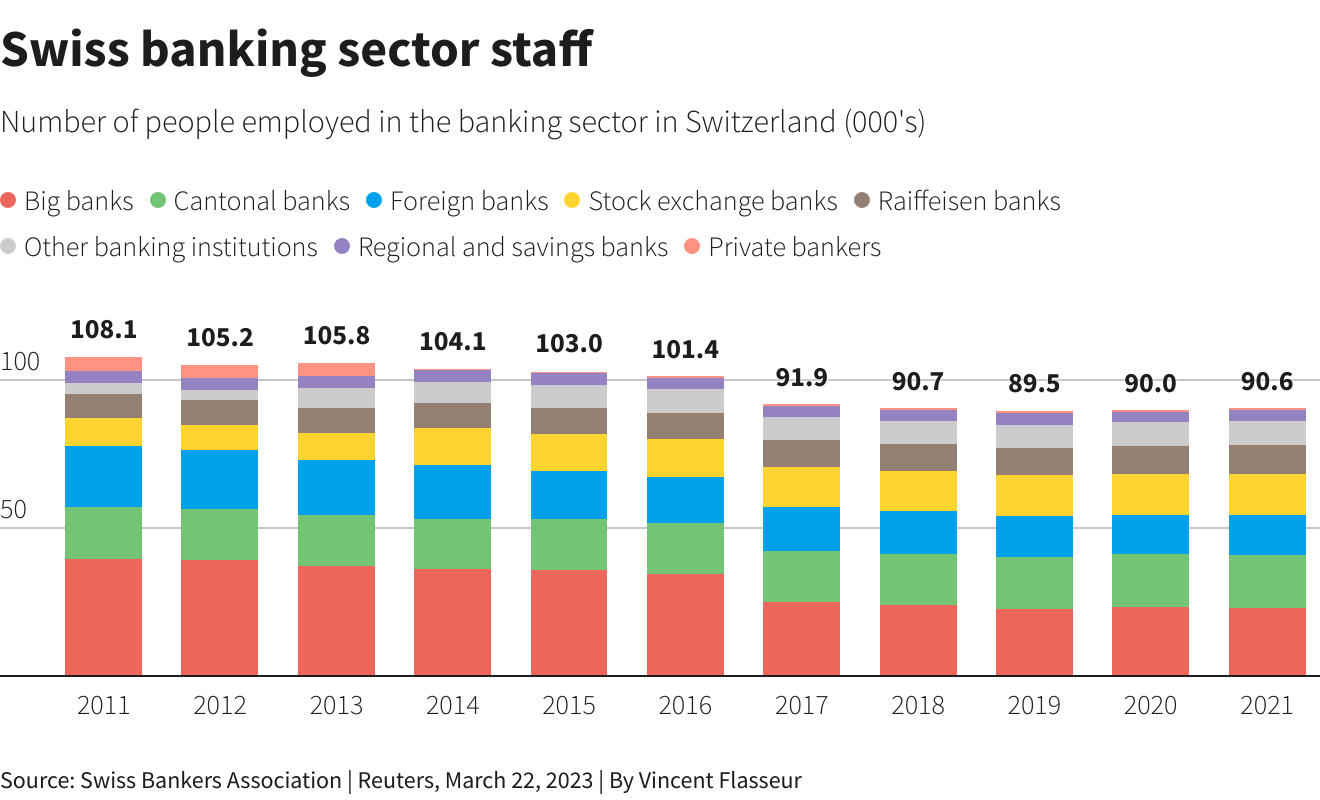

Still, the number of banks has fallen, down to 239 in 2021 from 356 in 2002. Staff numbers since 2011 have slipped to 91,000 from 108,000.

"There are a lot of open questions: the use of emergency law overriding the views of shareholders or the treatment of bond holders," said Stefan Legge, head of tax and trade policy at the University of St. Gallen's IFF Institute for Financial Studies.

"Maybe some people are a bit delusional – and really believe they are doing a great job."

Switzerland invoked emergency legislation to allow a public liquidity backstop (PLB) which will provide up to 100 billion Swiss francs in liquidity to Credit Suisse as the PLB was not yet part of Swiss law.

But perhaps most controversially, the emergency law allowed the takeover to go ahead without shareholder approval.

Legge said the collapse should serve as a wake-up call, and could see new laws to improve corporate governance introduced.

Switzerland has few mechanisms for holding top bankers individually responsible for mismanagement, unlike centres such as Britain where senior managers can face criminal sanctions.

Unions and politicians have also reacted angrily to the rescue, which could leave the taxpayer having to cover up to 9 billion francs in losses.

LONG DECLINE

Switzerland's outsized banking sector has been under pressure for years following a decline in banking secrecy as other countries sought to clamp down on tax evasion by citizens.

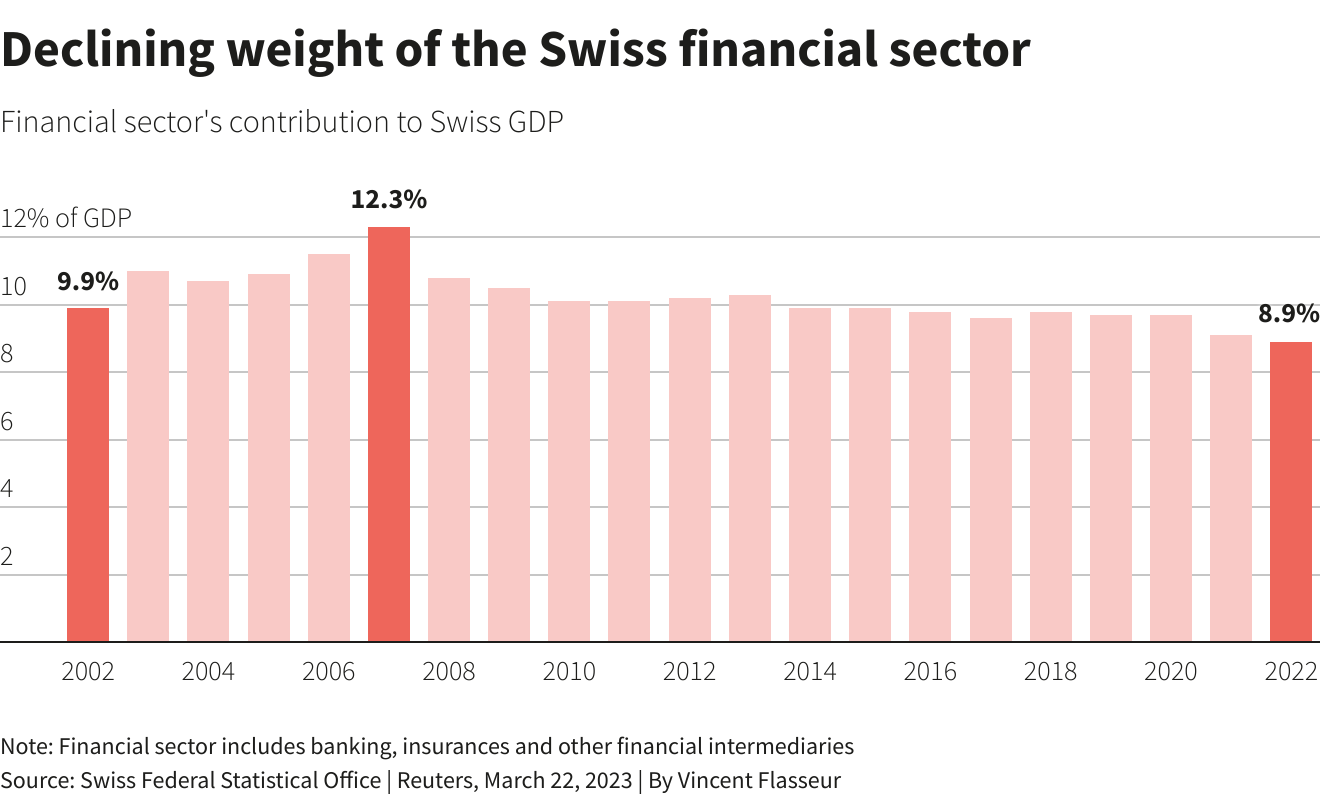

The financial sector's contribution to the Swiss economy has also slipped, falling to 8.9% of Swiss GDP in 2022 from 9.9% in 2002 as industries like pharmaceuticals became more important in a country with the third highest GDP per capita in the world, according to IMF data.

BAK Economics, a Swiss research institute, said the fallout from the debacle would be contained within the banking sector. It estimated up to 12,000 Swiss jobs being lost, although the impact on the broader economy would be limited.

Jan-Egbert Sturm director of the KOF Swiss Economic Institute at ETH Zurich, a university, predicted the economic impact of Credit Suisse's demise would amount to a loss of around 0.05% of GDP per year.

Switzerland's long banking tradition and structural advantages meant the country would remain heavily involved in banking in future, he said, with investors still choosing it for its stability and the strength of its Swiss franc currency.

Still competition was getting fiercer, and the recent events would eventually see Singapore overtake Switzerland, warned IMD's Bris.

"I think it's only a matter of time."