Hong Kong News

An ancient group of Hong Kong inhabitants loved their seafood, to an extreme

Whether booking a semi-private ferry to grab dinner on Lamma Island, the third-largest island of Hong Kong, a trip to the fishing village of Lei Yue Mun or an evening on Sai Kung’s touristy promenade, Hongkongers will make quite the effort for the freshest seafood the city has to offer.

And if we were to visit the people who lived in the area 4,000 years ago, we would have found a similar love for seafood, although it was taken to the extreme.

A study published in The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology in late February found that a small population of neolithic Hongkongers were highly reliant on fish.

Christina Cheung, a researcher at Vrije Universiteit Brussel in Belgium who wrote the study, said these people were so reliant on seafood that they probably did not rely much on farming for food or hunting land animals.

“For people who lived in a coastal area, I would expect them to eat some marine food, but I was surprised to see that, in these ancient Hong Kong people, they were reliant on marine protein to such an extreme extent,” she said.

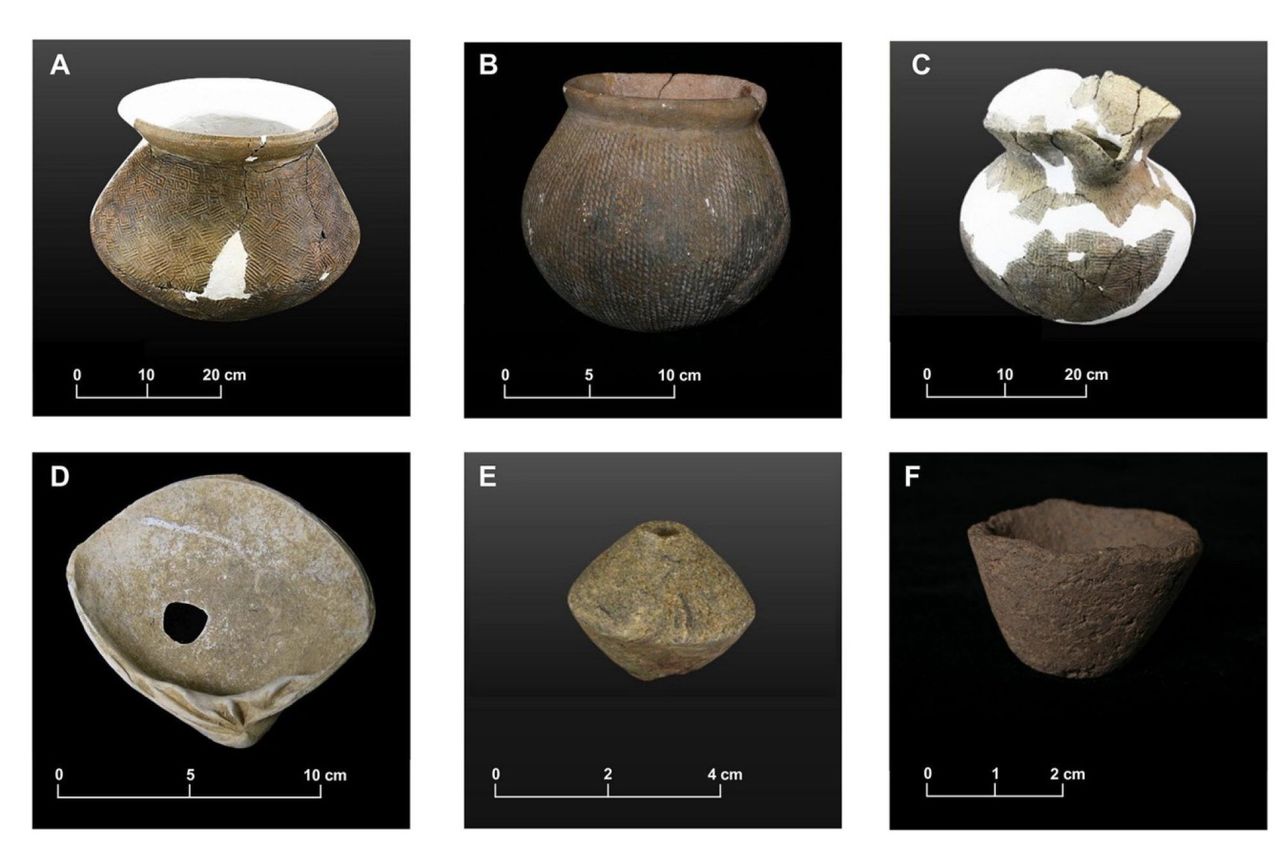

Neolithic artefacts discovered in Hong Kong.

Neolithic artefacts discovered in Hong Kong.

The study analysed bone samples from a group of 13 neolithic skeletons found on Ma Wan island at a site called Tung Wan Tsai, which modern Hong Kong residents may recognise as a small beach next to the island’s ferry pier.

Cheung found the people had a diet with few known peers in southern China or Southeast Asia.

Similar studies on neolithic peoples from Vietnam, Thailand and Fujian province in southeast China showed a much higher proportion of their diet came from the land. Even skeletons found locally in Pui O and Lamma Island indicated a more terrestrial diet – which the study suggested could be due to the simple fact that Lamma and Lantau are far larger islands than Ma Wan.

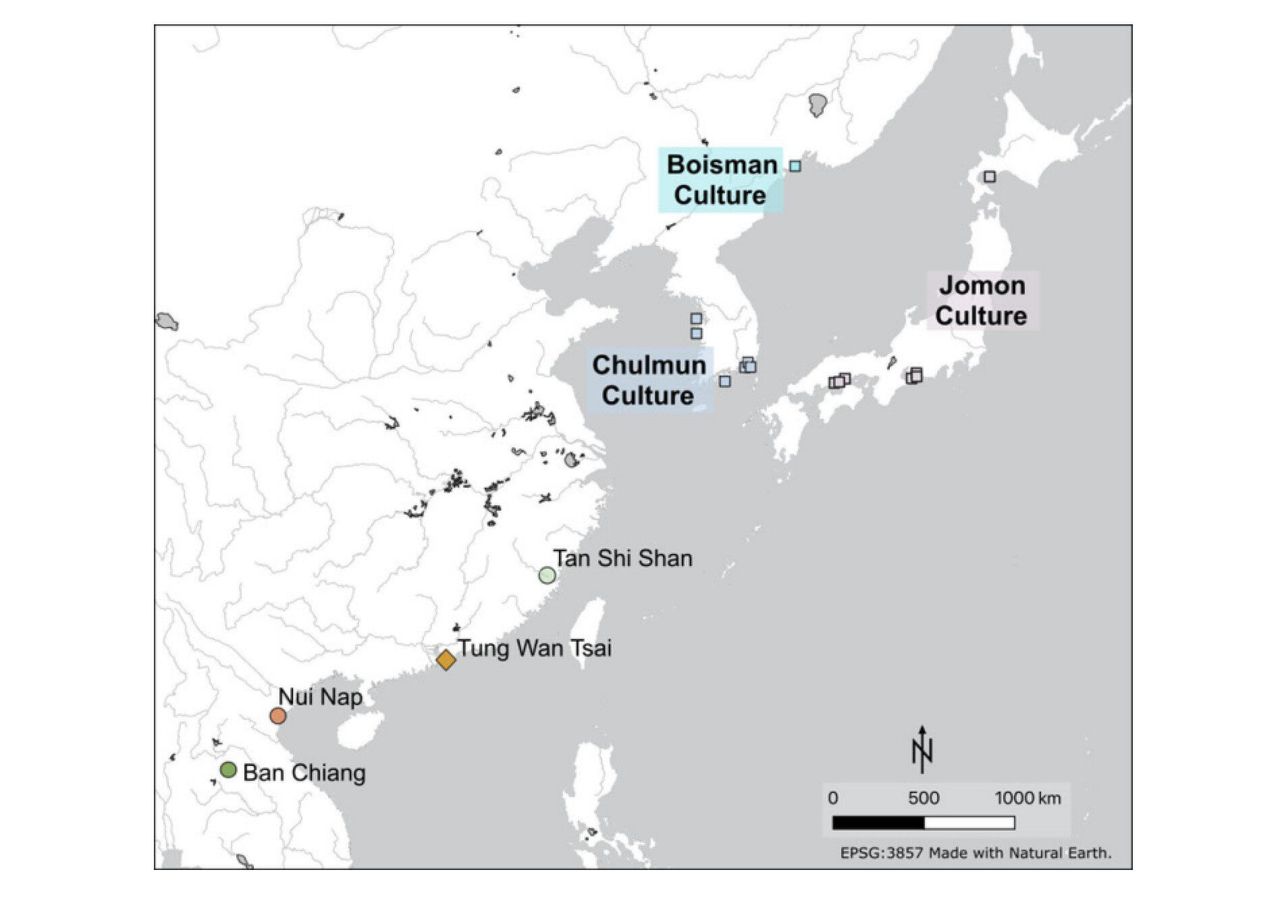

The cultures that did have similarities to the Ma Wan community were the Chulmun culture on the Korean peninsula, the Jomon people in Japan and the Boisman in the Russian Far East.

“I was not trying to compare the type of food they ate, but this site in Hong Kong is unique in that it is not comparable to the region, but it is more similar to regions that are very, very, very far north,” said Cheung.

The diets of the people found in Ma Wan were similar to cultures that lived much further north.

The diets of the people found in Ma Wan were similar to cultures that lived much further north.

As for what type of seafood the Ma Wan people may have eaten, zooarchaeological findings in the area point to large deepwater fish, molluscs, dolphins, sharks and porpoises. The study hypothesised that this meant the people were advanced fishermen capable of targeting large fish.

The scientists were able to determine the diets of ancient Hongkongers through a bone analysis process that Cheung said, “is very much like making soup”.

This set of 13 bones had been processed 20 years ago by Brian Chisholm, a senior instructor emeritus at the University of British Columbia in Canada and another author of the study.

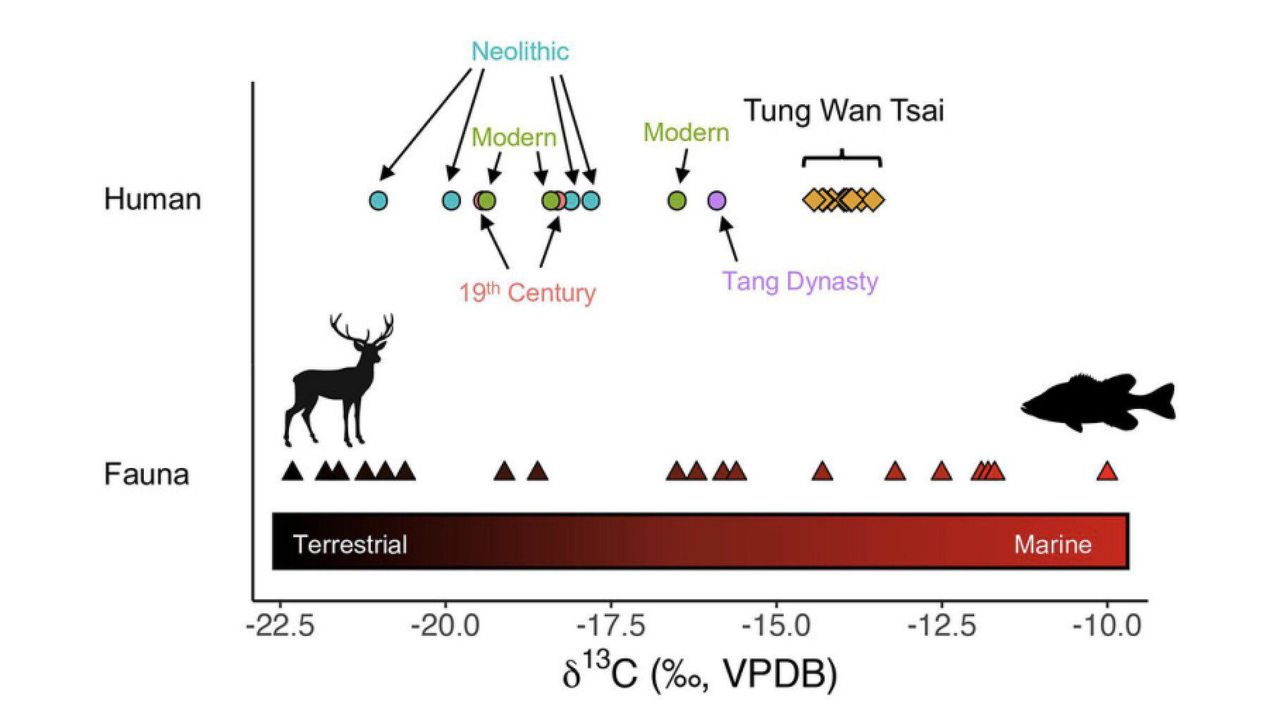

Cheung was given the data last year and, by analysing the stable carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios in the bones, she found a chemical signature that is distinctively an outlier on charts when compared to diets from other contemporary sites. Cheung said the stable nitrogen isotope values from the Hong Kong bones was “extremely high and almost impossible to get from eating terrestrial food.”

A chart outlines typical diets for modern, neolithic, 19th century and

Tang dynasty humans (circles) when compared to the people found in Hong

Kong (diamonds).

A chart outlines typical diets for modern, neolithic, 19th century and

Tang dynasty humans (circles) when compared to the people found in Hong

Kong (diamonds).

For Cheung, discovering the extreme seafood diet led to a cultural connection to her family, which is from fishing villages in Chiuchow, an area in the northern part of Guangdong province in southern China that is famous for seafood dishes.

“When I saw the results, I was like ‘yes!’, because in Europe, and also when I did my PhD in Canada, we do not often see a modern culture that is this intensive about seafood. I felt very proud about this,” she said.

“I am used to eating fish, and I eat a lot of fish compared to my friends, but not compared to my parents. And I don’t eat fish for breakfast, but my dad does. He is super intense.”