Hong Kong News

Across the U.S., Streets Named After Martin Luther King Jr. Remain a Battleground for Equality

Melvin White remembers exactly where he was when the idea came to him.

"I was a mail carrier, so I’m delivering mail on the street and thought, ‘Wow, this doesn’t make sense,’" he says. "Abandoned buildings, drugs being sold. This is a really bad street. You look at the name on the street sign and I was like, ‘This does not correlate with what he stood for.’"

A dilapidated building sits on Dr. Martin Luther King Drive in St. Louis, Missouri. Scenes like this inspired Melvin White to found Beloved Streets of America, a nonprofit organization aiming to revitalize the street and surrounding areas.

That "he" is Martin Luther King Jr., for whom hundreds of streets nationwide are named after. In White’s hometown of St. Louis, Dr. Martin Luther King Drive cuts through a neighborhood that’s seen better days. Formerly Easton Avenue, it was once a bustling business district in the first half of the 20th century. Boutiques, restaurants, and department stores like J.C. Penney and Woolworth used to dot the busy avenue.

Today, the glossy department stores are gone, replaced with vacant buildings and lots. Some commercial development has come to the area, but it’s been a slow trickle over the last two decades or so.

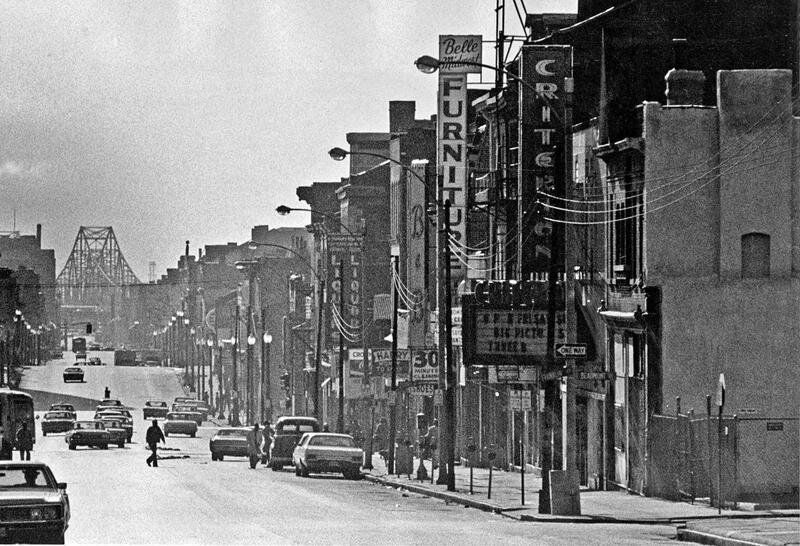

An archival image shows Dr. Martin Luther King Drive in St. Louis in May 1972.

But White is on a self-bestowed mission to recapture the activity and energy the area was once known for. In 2009, inspired by his walks and drives around the community, he established Beloved Streets of America, which aims to counteract the urban decline of communities surrounding the streets named after King and provide a positive environment for local residents.

"Our vision is that every street in America that bears Dr. King’s name is vibrant, beautiful, and a prosperous community," says White.

"Growing up, Dr. King was my hero," White says. "Looking at that street, if you’ve been to St. Louis, you can see the blight. We should have a beautiful street to be in line with his legacy."

The first MLK street renaming took place in Chicago in 1968, just months after the civil rights icon was assassinated. The initial proposal was to either name a street that cut right down the prominent central business district of Chicago, or one of the new big expressways that was going to wrap around the city.

"The activists and leaders within the Black community who wanted to remember King wanted a major prominent thoroughfare," explains Derek Alderman, professor of geography at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, who’s extensively studied the politics of naming streets for King. "Chicago refused to do that. In fact, Mayor Daley basically, in effect, hijacked the proposal."

Daley and his administration ultimately decided that King’s name would be placed along a road that was virtually confined to the Black community and the South Side, ignoring what Black organizers sought in a move that Alderman describes as a misuse of power.

"That pattern that happened in Chicagoขwhere you have white leaders almost appropriating King’s nameขis a pattern we see on and on," he says.

Dunbar High School students in Chicago cover up the name of South Parkway after the city council votes to rename it Martin Luther King Drive in 1968.

Chicago History Museum

The movement to name streets after King picked up more speed in the 1970s and gained major traction in the early and mid-1980s with the establishment of the federal holiday, which was first observed in 1986.

"The King holiday was a real turning point for naming streets for Dr. King," Alderman says. "The reason a lot of communities wanted to name the street for King is they wanted a permanent, fixed, physical memorial to King. They wanted to provide something the holiday could not."

In the decades since, MLK streets across America have developed a persistent reputation for being located in struggling, derelict, or dangerous areas. But it’s not exactly an accurate reputation.

While new research shows that poverty rates are almost double the national average in areas surrounding streets named after King, and educational attainment is much lower, that’s not necessarily proof that a street being named after King is a harbinger of urban decline.

What’s more, time and time again, white people in communities from Florida to Oregon have pushed back against renaming, assuming it would lead to boarded-up businesses and an uptick in crime. That sometimes means more affluent, majority-white communities that resist renaming lead to MLK streets being placed in a Black community that isn’t as economically developed.

In Chattanooga in the early 1980s, for instance, local activists wanted to rename 9th Street after King. The city council agreed to the proposal - sort of. According to Alderman, they agreed to rename only one half of the street that was more closely connected to the Black community. A business developer on the other half of 9th Street was vehemently opposed to an MLK address on the ground.

"He stated-and went on the record as stating-that he thought it was bad for business," Alderman says. "He thought it would bring down property value. It’s the litany of reasons you hear from many opponents, even today. It would ‘discourage customers.’ It’s just offensive, what he was saying."

Deirdre Mask, author of The Address Book: What Street Addresses Reveal About Identity, Race, Wealth, and Power, who has a chapter dedicated to streets named for King, says some arguments about MLK streets being worse off than anywhere else have been debunked.

"Some researchers have said they’re more impoverished areas and certainly, some are absolutely in some of the poorest parts of the country," Mask says. "But some researchers actually found something really interesting: If you compared Martin Luther King streets to Main streets or JFK streets, in terms of economic activity, they really weren’t worse off. It’s just more economically different."

For example, Mask explains, on many MLK streets, you’ll often find more churches and schools.

"That makes a lot of sense when you consider that Black people were effectively excluded from white collar jobs, like accountancy and law," Mask says. "It makes sense that the highest point that a lot of Black people could reach in their careers would have been-the most respectable jobs would have been-preachers and teachers. It doesn’t necessarily make them worse."

Perception is at the heart of the MLK streets conversation because perceptions of race and economic prosperity influence what someone views as a "bad street" and a "nice street." Mask cites the MLK street in her hometown of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, as an example of a place that would likely garner that "nice" reputation.

A tree-lined Martin Luther King Jr Boulevard in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

"It’s a nice, very economically active, and vibrant street," Mask says. "Do we continue to see MLK streets as being bad streets because we think any street that’s a Black street has to be a bad street? Is our linking of MLK streets in a negative light just because we see Black people in a negative light, and we can’t imagine a Black street could be a nice street?"

After all, who gets to define "nice" anyway? The subjectivity of what "nice" means certainly complicates the efforts of someone like White, though it doesn’t invalidate them. Because while no two MLK streets are the same, one universal truth is that when it comes to deciding what a "success story" looks like, that should be left to the people who live and work along these streets. For far too long, their voices have been ignored or silenced.

"Certain people would think a success story of an MLK Street is a Trader Joe’s and some cafes," Mask says. "But for a lot of people in these communities, that’s not their culture. That’s not really what they want. In terms of success, that’s something each community has to define for itself."

White has set out to do just that with Beloved Streets of America. He knows what his community wants because he’s been on the ground talking to people. So far, the organization has raised enough money to purchase several abandoned buildings to begin revitalization efforts along and around MLK Drive in St. Louis.

"A success story is when you’re able to take some of these abandoned businesses where nobody’s at, to be able to create jobs, to make it a thriving community," says White. "Because it used to be at one point where, if you’re in a neighborhood, you can walk right around the corner to the store. [There’s] not even a decent grocery store in the neighborhood."

"You have to focus on not only his street, but the surrounding areas to make a thriving corridor," White says. "We want to take vacant lots and turn them into urban gardens. Some of these vacant buildings, turn them into tech centers where you can have incubators for small businesses."

But these are big, and often pricey, projects. To date, White has relied mostly on private donations and at times has paid for expenses out of his own pocket. Now it’s just a matter of having the resources and funding to make those changes happen in St. Louis and along other MLK streets across the country.

"It’s hard to get people to really contribute," White says. "But it is not stopping me from anything. I’m gonna keep thriving and keep going as far as the mission and the vision goes."