Hong Kong News

A look back at events that shaped Hong Kong’s political landscape in 2021

Hong Kong has gone through a number of political changes since Beijing implemented a sweeping national security law in the city more than a year ago.

The legislation has affected many in the opposition camp, resulting in the arrests of a number of activists and prominent civil rights groups disbanding. Press freedom came under the spotlight as well, as Apple Daily folded after 26 years in business.

Beijing also overhauled the city’s electoral system, and has since issued full-throated rejections of Western-style democracy, even as it renewed its commitment to allowing Hong Kong to elect its leader by universal suffrage.

Below, the Post highlights some of the political events that have defined 2021.

The 47

The year began with the arrests of 53 activists and former opposition lawmakers under the Beijing-imposed national security law at the start of January. Two months later, 47 of them were charged with conspiracy to commit subversion over an unofficial primary the opposition camp had organised for last year’s Legislative Council election, which authorities later postponed.

Prosecutors argued in court that the primary formed part of a wider plan opposition politicians had hatched to seize control of the legislature in order to paralyse the government and topple the city’s leader. Apart from being the largest prosecution under national security law to date, the case was also notable for its lengthy bail hearings, one of which lasted long past midnight.

Only a handful of defendants have been granted bail, with the majority now behind bars waiting for a trial date, which has yet been set. In the months that followed, police have continued to arrest people under both the national security law and the city’s little-used, colonial-era sedition law, including several speech therapists accused of inciting hatred towards the government over a series of children’s books.

‘Patriots’ only

In March, Beijing introduced sweeping changes to the city’s electoral system, imposing the principle of “patriots” ruling Hong Kong. As part of the overhaul, a powerful vetting committee was established to ensure candidates in the city’s coming elections posed no threat to national security.

A Beijing-led electoral shake-up meant only “patriots” can serve in the city’s legislature.

A Beijing-led electoral shake-up meant only “patriots” can serve in the city’s legislature.

The Election Committee, originally a 1,200-strong group responsible for choosing the chief executive, was given a boost of 300 seats, but the voter base for electing its members was reconfigured to give Beijing’s loyalists more influence. The committee was also given a new power to nominate lawmakers.

Under the shake-up, the legislature was expanded from 70 to 90 seats, with 40 going to the Election Committee constituency and 30 to the functional constituencies. But the number of directly elected lawmakers returned in the geographical constituencies was slashed from 35 to 20.

Western governments have since criticised the move as a way to stifle dissent, but Beijing and the Hong Kong authorities defended the system, saying that it was natural for a country to require its governors to be patriots and that foreign leaders should not interfere with China’s internal affairs.

Campus strife

The year also saw various universities distancing themselves from their student unions, which had traditionally played a significant role in the city’s democratic movement.

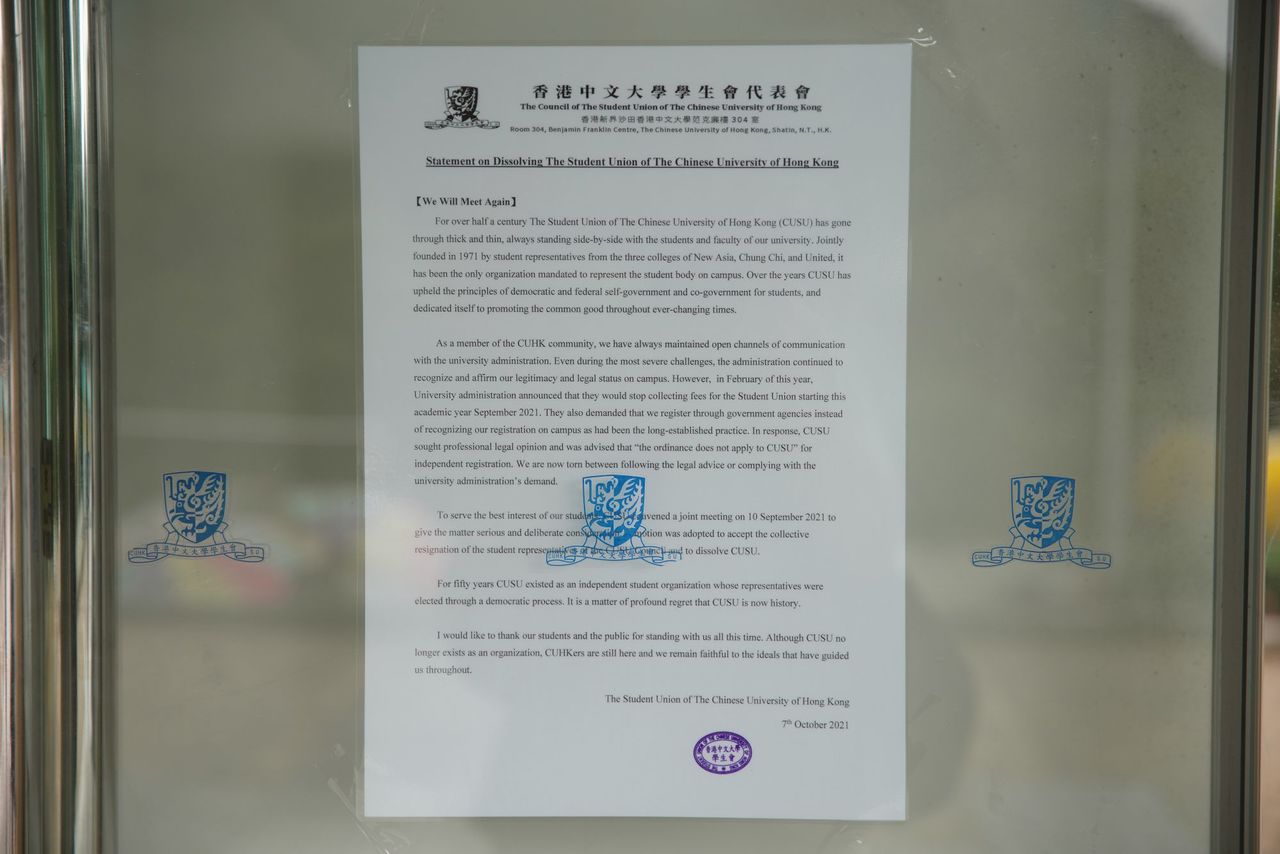

In February, Chinese University became the first tertiary institution to cut ties with its student representatives after the union criticised the national security law as an infringement of human rights.

A notice posted on the dissolution of the student union at Chinese University.

A notice posted on the dissolution of the student union at Chinese University.

In April, the University of Hong Kong (HKU), the city’s oldest tertiary institution, followed suit, also accusing students of spreading “propaganda”. HKU went a step further in July when it disowned its student union entirely, after the union’s council passed a motion to express “deep sadness” at the death of an attacker who stabbed a police constable on duty in Causeway Bay on July 1, before turning the knife on himself. The motion was withdrawn, but four students were charged with advocating terrorism under the national security law.

Apple Daily, Stand News fold

Press freedom came under the spotlight in June when national security police raided the offices of Apple Daily and arrested six senior staff members, including its publisher and editor. The 26-year-old tabloid-style newspaper founded by media tycoon Jimmy Lai Chee-ying folded after the arrests, and after police froze HK$18 million (US$2.3 million) worth of its assets.

Prosecutors charged the staff members with colluding with foreign forces by using the newspaper to call for foreign sanctions. They faced additional charges earlier this week of publishing seditious content.

Déjà vu struck when earlier this week police raided the office of Stand News, an online news portal, and arrested seven people over an alleged conspiracy to publish seditious content. All seven have been detained without bail, with the portal’s editor and his predecessor charged with the offence. The website halted operations after police froze HK$60 million of its assets.

Police raid the offices of Stand News, an online platform accused of publishing seditious material.

Police raid the offices of Stand News, an online platform accused of publishing seditious material.

Earlier in the year, the government appointed Patrick Li Pak-chuen, a former deputy secretary for home affairs, as the new director of broadcasting for RTHK. Current affairs programmes and popular talk shows have since been pulled.

Opposition fleeing, wanted list grows

Since the imposition of the national security law, a growing number of opposition figures have fled Hong Kong, including former lawmakers Nathan Law Kwun-chung and Ted Hui Chi-fung. Lee Wing-tat, chairman of Democratic Party, was reported to have headed to Britain.

Stand News director Tony Tsoi Tung-ho is the latest person to be added to police’s wanted list.

‘Lifeboats’ for Hongkongers

Canada and Australia have unveiled their versions of so-called “lifeboat” schemes, pathways offered by Western countries for Hongkongers to move abroad in response to the imposition of the national security law.

Nearly 80,000 Hongkongers have taken advantage of a so-called lifeboat scheme offering residency in the UK.

Nearly 80,000 Hongkongers have taken advantage of a so-called lifeboat scheme offering residency in the UK.

Under another scheme offered by the United Kingdom through the British National (Overseas) visa, some 88,900 Hongkongers have applied since its introduction on January 31, of whom 76,176 have been approved. But the trend is slowing down, according to the latest figures from the British government in November.

Civil groups disband

The months from August to October saw the disbandment of several prominent civil rights groups, such as the opposition-leaning Professional Teachers’ Union and Confederation of Trade Unions, as well as the Civil Human Rights Front, the organiser behind some of the city’s biggest rallies. More than 50 groups have been dissolved in the past year.

The Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, which organised the city’s annual vigil marking the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, was also among the groups that folded. Three of the alliance’s leaders have been charged with inciting subversion, while others also face a charge of refusing to provide certain documents under the national security law.

The Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of

China, organiser of the city’s annual Tiananmen vigil, was among the

groups to disband this year.

The Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of

China, organiser of the city’s annual Tiananmen vigil, was among the

groups to disband this year.

Opposition councillors disqualified

The city’s district councils, envisioned as advisory bodies for the government at the municipal level, became a stronghold for the opposition camp after a landslide win in the 2019 elections.

Following the imposition of the security law in June last year, the requirement that top officials, legislators and judges pledge allegiance to the city was extended to all public officers, including civil servants and district councillors, to ensure they were sufficiently patriotic. Rounds of oath-taking ceremonies were held starting in September for district councillors.

As a result, 55 opposition district councillors were disqualified.

Record low turnout

Earlier this month, Hong Kong held its first Legislative Council poll since the electoral overhaul ordered by Beijing. The turnout rate – 30.2 per cent – was the lowest since Britain handed the city back to China in 1997.

All but one newly elected lawmaker belong to the pro-establishment camp. The exception is Tik Chi-yuen, a centrist who won in the social welfare functional constituency.

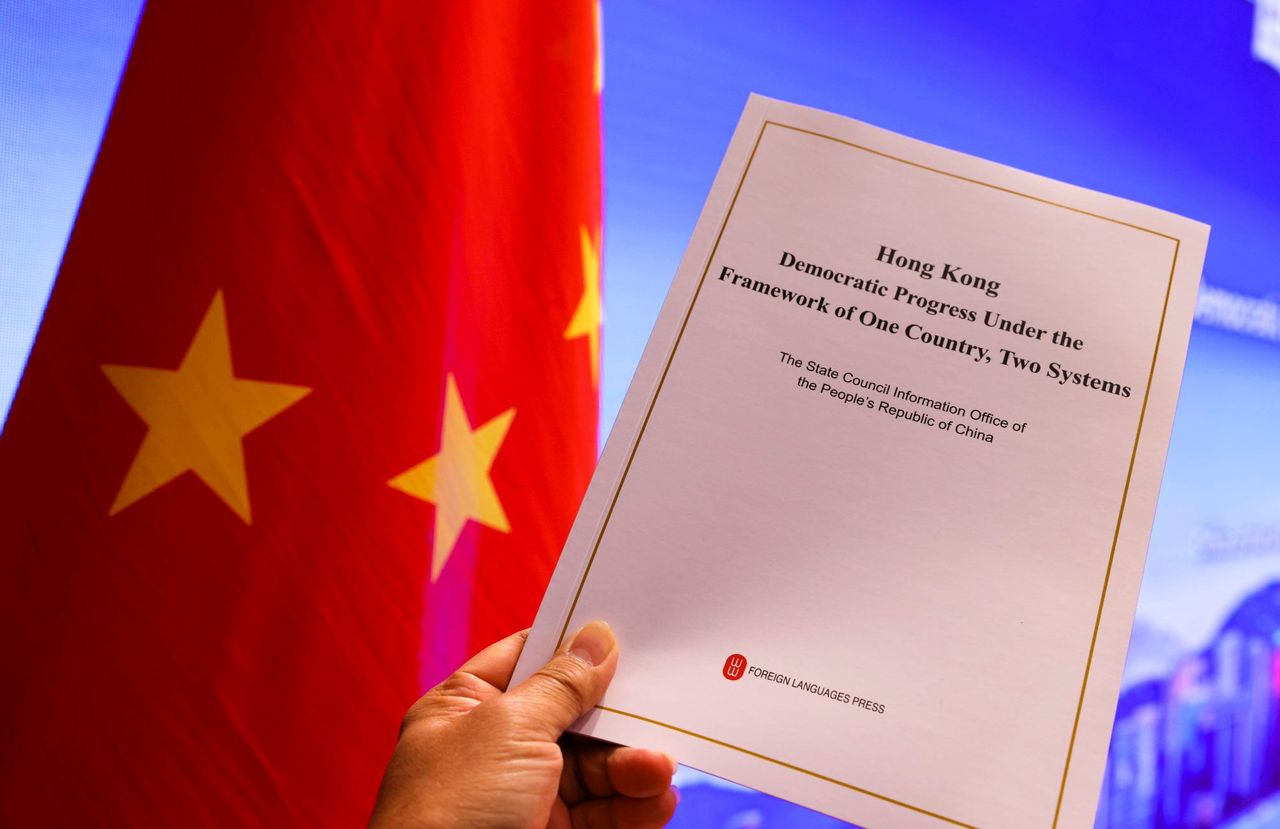

Beijing’s white paper

Beijing issued a white paper following the Legco election defending its approach to democracy in HOng Kong.

Beijing issued a white paper following the Legco election defending its approach to democracy in HOng Kong.

Almost immediately after the Legislative Council election, Beijing issued a white paper offering a robust defence of its strategy of developing democracy for Hong Kong “in line with its realities” and putting “patriots” in charge.

The Legco election had been cited by the West as an example of oppression in the city, but Beijing hit back, arguing that Britain never offered democracy when Hong Kong was under its rule and that the white paper exposed the double standards.